The Mustard Pickle Tragedy Unfolding in Newfoundland

The disappearance of a favorite condiment brand is rocking the island to its core.

On a Friday afternoon in early March, grocery stores all over Newfoundland dealt with an unusual rush. Customers ran in, asking frantically after particular items. Phones rang as family members placed requests. Beneath the cheerful shopping music coursed a vague yet undeniable current of panic.

Outside, though, no winter storm approached, and the purposeful shoppers walked right past the water and the flashlight batteries. They were after something far more precious: the last of the mass-produced mustard pickles.

After years of faithful service, Smucker’s had announced the end of its beloved Zest and Habitant brands, meaning an end to easily-available, off-the-shelf mustard pickles. “Kiss your pickle goodbye,” read one headline in the Telegram, the “people’s paper” of the province.

But Newfoundlanders have a sweet kick equal to their favorite condiment. They weren’t about to let go without a fight.

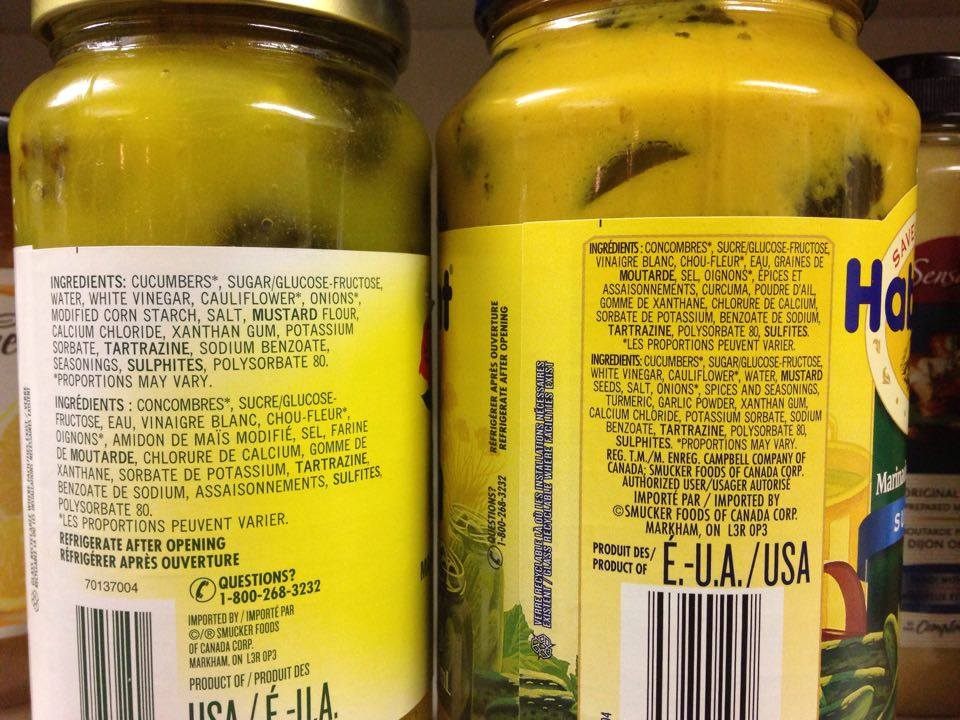

A jar each of Zest and Habitant. (Photo courtesy Amy Anthony)

A mustard pickle is essentially what it sounds like—cucumbers, onions, and cauliflower, chopped up, brined, and smothered in a thick yellow sauce. When jarred and lined up in a pantry, mustard pickles look both sunny and vaguely menacing, like a row of Don’t Walk signs. Their flavor is similarly complex: a good mustard pickle, says chef Amy Anthony, is “a harmonious balance of sweet, acid, and all the mustard.”

But food, of course, is more than its ingredients, and the true appeal of the condiment surpasses its zingy crunch. After helping generations of Newfoundlanders survive, mustard pickles are now “at the core of our cultural identity,” says Felicity Roberts, a food writer for alternative newspaper The Overcast. “Deep traditional roots here, not taken lightly.”

It was Newfoundland’s climate that first gave pickles their due. The island, which locals sometimes call “The Rock,” is cold for much of the year, and there’s not a lot of topsoil to go around. Before the advent of grocery stores, Roberts explains, easily preserved foods—salt cod, cabbage, dried peas—got residents through long, barren winters.

Pickles in particular had a couple of things going for them. You could keep a jar in the cellar for months, and when you cracked it open, its contents would still taste new. “It was a way to get a bit of zing in your otherwise salty, fatty, bland meal of root vegetables and salt meat,” Roberts says. “It was just something that made food a little bit more interesting.”

Is Jiggs Dinner the official food of #NFLD @ToddPerrin, @kimdoyleot, @mallardchefgary? https://t.co/cdiPw51wYT pic.twitter.com/EYNREX6BwQ

— Restaurants Show (@RestoShow) December 20, 2015

Mustard pickles also play a sort of “Best Supporting Side” role in what’s known as Jiggs dinner, an end-of-week meal made up of salt beef, pease pudding, and root vegetables all cooked together. “Like most Newfoundlanders, I ate this every Sunday until my great grandmother died,” says Roberts. The dish is named after the main character from a 20th-century Irish-American comic strip, “Bringing Up Father.” Jiggs, the father in question, would skip his wife’s fancier dishes and sneak out to the pub for his favorite boiled meal, which reminded him of his working-class roots.

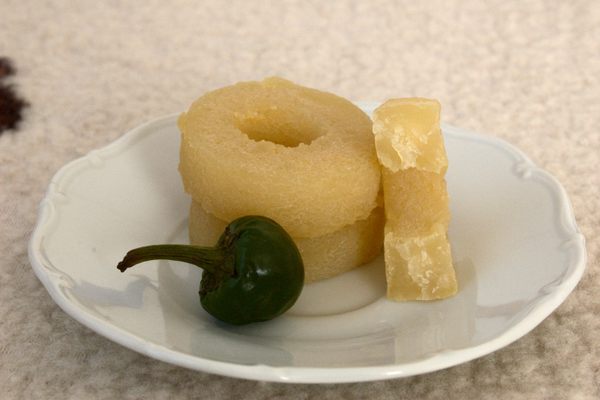

Even the entrance of modern conveniences has failed to phase out the pickle. Today’s Newfoundlanders still eat Jiggs dinner with mustard pickles, but they also stack the briny veggies on cod cakes, cook them into croquettes, or snack on them straight out of the bottle. Meanwhile, new traditions emerge. Anthony remembers “full on wrestling over the piece of cauliflower” during a day of drinking with friends. When asked about his personal pickle usage, restaurateur and cookbook author Mark McCrowe says, simply, “I put that shit on everything.”

Chef Amy Anthony shows off a mustard pickle cauliflower, which she calls “the golden nugget.” (Photo courtesy Amy Anthony)

But zing and tradition can’t fill the coffers of international corporations. It used to be that those who didn’t feel like bottling their own mustard pickles or buying local could pick up mass-produced ones, made by Smucker Foods of Canada. But in early March, Smucker’s discontinued two of its beloved brands: Zest, an acidic, cauliflower-heavy pickle, and Habitant, a thicker, more mustardy one. Smucker’s tried to do this quietly—the news only broke thanks to a local restaurant owner, who was confused when he couldn’t put in his usual order for a shipment—but the company later told the Telegram they made the decision due to lack of consumer demand.

Spurred into action, said consumers quickly got extra-demanding. Many raided local supermarket shelves. The Heritage Foundation began soliciting family recipes. One enterprising Zest fan allegedly put his stockpile up for resale online at a 400 percent markup, a price he called “god damn reasonable unless yer a cheap arsehole who wants to serve a half assed Sunday dinner.”

Kiddo just had her first, and probably last, Zest Mustard Pickle… 😢 #PickleCrisis pic.twitter.com/HZ6FKeowbW

— Mitch Colbourne (@MitchWearsPlaid) March 6, 2016

Others headed straight to mourning. People photographed their last jars, and grieved for future, Zest-less generations. Singer-songwriter Gregory Crane posted an original dirge on Facebook: “Go get your pickles each woman and man,” he sings dolefully, strumming a guitar. “‘They surely will be missed; that bottle looked grand.” (The video currently has 61,000 views.)

Meanwhile, demand for small-batch pickles soared, and local foodmakers saw an opportunity for some lucrative heroics. “We thought we were going to be pickle barons,” says Roberts, whose partner owns a company that sells jams and preserves. “I was like, ‘gourmet mustard pickles, now! Basil mustard pickles, jalapeno mustard pickles! Strike while the iron is hot!’”

Soon after the initial ruckus, the iron cooled somewhat, as several bigger pickle players stepped in to fill the void. Smucker’s announced it would be updating its third mustard pickle type, Bick’s Sweet Mustard Pickles, to taste more like the abandoned other two. Grocery store Colemans, which bore the brunt of the emergency rush, is developing a store-brand pickle they swear is “way better than the Zest.”

Don’t leave yourself in a pickle this Easter! Enter to win one of the last remaining cases of Zest Mustard Pickle! pic.twitter.com/RiwSnEwVXA

— Colemans (@colemansfoods) March 17, 2016

Fans have their doubts. But despite the loss of two populist favorites, Roberts thinks the episode may have been good for the mustard pickle. “It’s kind of given them a little resurgence,” she says. “It became quite the hipster thing in the past few weeks, to show up with a jar of mustard pickle.” Roberts knows of “at least one person” who got the rose from the Zest pickles logo tattooed on an arm.

“Someone compared them to when a mediocre artist dies: you never really cared in life, but suddenly it’s like, ‘Oh my God, I need their albums,’” she says. “I think for a lot of people this was an awakening.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook