The Public Shaming of England’s First Umbrella User

This pioneer of weather management was pelted with insults and trash.

Jonas Hanway walking into the rain, with—controversially—an umbrella. (Photo: Bettmann/Getty Images)

In the early 1750s, an Englishman by the name of Jonas Hanway, lately returned from a trip to France, began carrying an umbrella around the rainy streets of London.

People were outraged. Some bystanders hooted and jeered at Hanway as he passed; others simply stared in shock. Who was this strange man who seemed not to care that he was committing a social sin?

Hanway was the first man to parade an umbrella unashamed in 18th-century England, a time and place in which umbrellas were strictly taboo. In the minds of many Brits, umbrella usage was symptomatic of a weakness of character, particularly among men. Few people ever dared to be seen with such a detestable, effeminate contraption. To carry an umbrella when it rained was to incur public ridicule.

The British also regarded umbrellas as too French—inspired by the parasol, a Far Eastern contraption that for centuries kept nobles protected from the sun, the umbrella had begun to flourish in France in the early 18th century when Paris merchant Jean Marius invented a lightweight, folding version that, with added waterproofing materials, could protect users from rain and snow. In 1712, the French Princess Palatine purchased one of Marius’s umbrellas; soon after, it became a must-have accessory for noblewomen across the country. Later British umbrella users reported being called “mincing Frenchm[e]n” for carrying them in public.

Umbrellas on the streets of Paris, in this 1803 painting by Louis-Léopold Boilly. (Photo: Public Domain)

Jonas Hanway, always stubborn, paid little attention to the social stigma. An eccentric man, he was no stranger to controversy—he fervently opposed the introduction of tea into England, at one point penning an “Essay Upon Tea and Its Pernicious Consequences” (1756). He published four books on the development of British trade in the Caspian Sea, leading 20th-century scholar Charles Wilson to call him “one of the most indefatigable and splendid bores of English history.”

Over the years, Hanway and his umbrella fell victim to all sorts of abuse from Brits he passed on the sidewalk. The most pernicious abuse came from an unlikely source: coach drivers. In England at the time, hansom cabs (two-wheeled, horse-drawn carriages) and sedan chairs were the primary modes of transportation. Business boomed especially on rainy days, as both hansom cabs and sedan chairs came equipped with small canopies that kept passengers dry. When it rained, Londoners flocked to these coaches, so Hanway’s umbrella represented a threat to business.

Fearing an interruption in their personal incomes, many hansom cab drivers and sedan chair carriers grew violent toward Hanway. According to the British history magazine Look and Learn, when they saw him walking by, they often “pelted him with rubbish.” On one occasion, a hansom cab driver even tried to run Hanway over with his coach. Hanway reacted by using his umbrella to “give the man a good thrashing.”

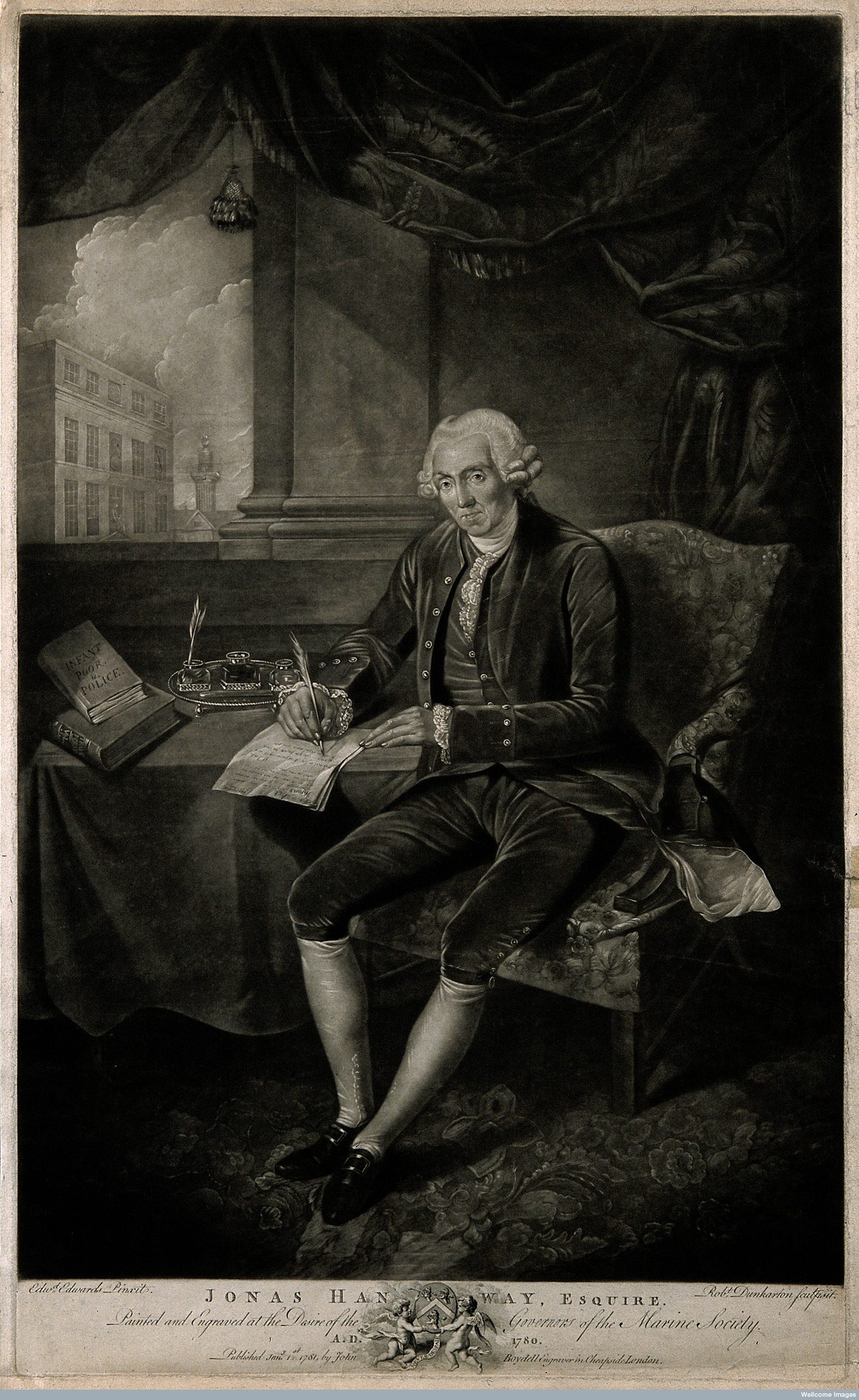

Jonas Hanway, Esquire, in 1781. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/CC BY 4.0)

The coach drivers, of course, were right to be afraid. With Hanway paving the way, the number of people who owned an umbrella crept upward across England. One historian observed that, soon after Hanway’s taboo-busting umbrella use, “in many of the large towns of the Empire, a memory [was] preserved of the courageous citizen who first carried an umbrella.” Almost every English town, in other words, had its own Hanway.

By Hanway’s death in 1786, umbrella usage was on the rise across England. On rainy days, more and more people could be found traversing their cities and towns with umbrellas held proudly above their heads. As a symbol of the changing social norms, people were also becoming less self-conscious about owning umbrellas.

Three months after Hanway died, much to the dismay of London’s coach drivers, an advertisement for umbrellas appeared in the London Gazette. “Gatward’s new invented Umbrella Manufactory,” it read, offered an umbrella capable of being “opened and shut with the greatest ease and facility” by means of an innovative “spring lock pillar.”

The rain-repelling revolution had begun, with the dearly departed Hanway as its pioneer. Not all heroes wear capes, but some carry umbrellas.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook