The Surprising Truth About Pirates and Parrots

A friend to pirates everywhere. (Photo: peasap/flickr)

Ever since Long John Silver clomped around on a wooden leg with a parrot on his shoulder, the literary and pop-culture conception of pirates has involved the parrot. But at this point, fact is very hard to separate from fiction. What, exactly, about a classic pirate Halloween costume—the parrot, the peg leg, the eyepatch, the bandanna, the snarling vaguely Scottish accent—is actually real? Is any of it real?

“The parrot trope is almost certainly grounded in reality,” says Colin Woodard, author of The Republic of Pirates: Being the True and Surprising Story of the Caribbean Pirates and the Man Who Brought Them Down. Long John Silver, the star of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, was the first major fictional pirate character to walk around with a pet parrot, but this, according to Woodard and other experts in the field of classic piracy I spoke to, was based on real truths. And the reasons why the parrot became associated with pirates actually give us a pretty good glimpse at the real, true-life existence of a pirate during the Golden Age of Piracy.

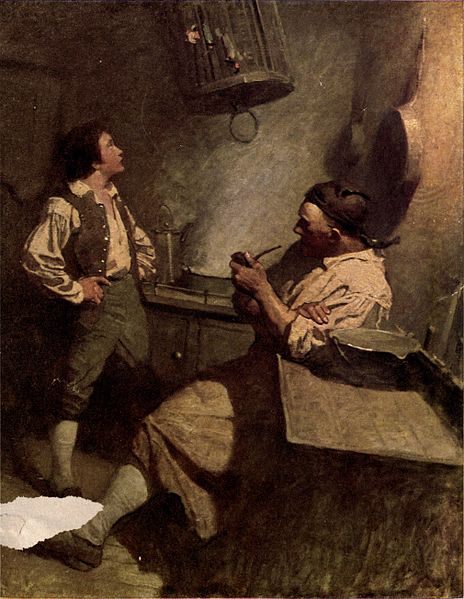

Long John Silver, Jim Hawkins and his Parrot, from the 1911 edition of Long John Silver. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The Golden Age of Piracy, a period lasting from, in the broadest sense, the mid-1600s through around 1730, encompassed a few different major geopolitical and economic movements that created a space for pirates. For one, the discovery of the Americas and Australia led to a boom in exploration, which in turn led to an absurd amount of money and valuables being ferried across oceans. Money, gold, slaves, spices, and other highly prized goods (“goods,” in the case of slaves) traveled back and forth. They were comparatively unprotected, the vastness of the oceans and the miserable conditions of trans-oceanic journeys leaving them weak and vulnerable. And many former sailors, with deep knowledge of the sea, wondered why they should bother the difficult slog of ferrying goods when they could simply steal them.

And so came the pirates.

Different portions of the Golden Age of Piracy, which is a term created by and endlessly argued over by pirate historians, resulted in different forms and different amounts of piracy. Angus Konstam, author of The History of Pirates and one of the foremost experts in the world, would prefer the term was restricted to an eight-year period from 1714 through 1722.

A French Ship and Barbary Pirates, c. 1615. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

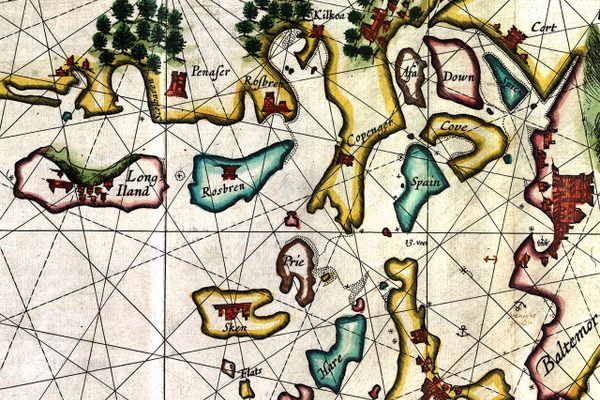

Regardless, pirates, depending as they did on robbing ships, mostly had to go where the ships were. They followed trade routes, which means they ended up in specific places; you didn’t see pirates flocking to deep South America or anywhere in the Pacific Ocean. They stayed with the ships, and ended up largely in the Caribbean, West Africa, and the Indian Ocean’s coasts.

On long trips, whether conducted legally or illegally, pets were desired but would need careful vetting. These long voyages, remember, could last weeks or months, and mostly, they were incredibly boring and uncomfortable. A companion animal could help ease the way. What kind?

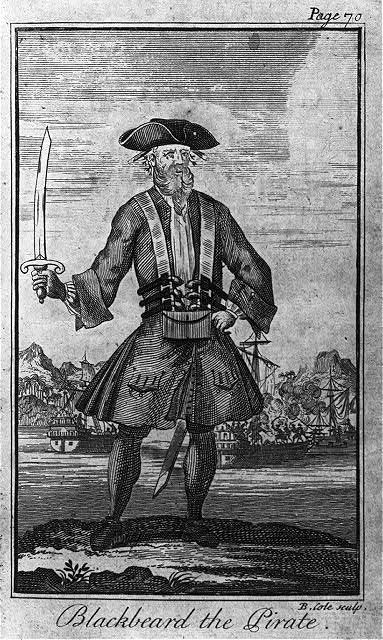

Capture of the Pirate Blackbeard, 1718. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

“I would reason that any large pet would be difficult to keep on a seagoing vessel, but cats might very much be prized for their ability to catch vermin like rats in the holds, etc of a vessel,” says Woodard. David Head, author of Privateers of the Americas, told me: “I’ve never seen references to dogs. Dogs as pets was more of an aristocratic thing in the early modern period.”

But pirates were traveling to exotic lands, had quite a bit of free time, had disposable income, and thus had no particular reason to restrict themselves to ordinary European pets like cats and dogs. Monkeys were not uncommon, and the concept of a pet monkey made its way into fiction as well—Captain Barbossa, in the Pirates of the Caribbean films, has one. But a parrot was more sensible. They don’t eat much, compared to a dog or a monkey, and what they do eat (seeds, fruits, nuts) can be easily stored on board. They’re colorful, and intelligent, and funny, and for a pirate (or a legal sailor) wanting to show off in port, a parrot would do nicely.

An engraving of Blackbeard the Pirate - but no parrot. (Photo: Library of Congress)

I asked the pirate experts I spoke to whether parrots would have been part of any sort of exotic pet trade. “Back home people would pay good money for parrots and other exotic creatures, and sailors could easily buy them in many Caribbean ports. Some were kept though, but most were sold when the ship reached home. They were colorful, they could be taught to talk—always entertaining—and they fetched a good price in the bird markets of London,” says Konstam. Woodard, though, noted that it might be tricky for a pirate to legally sell anything, especially an attention-grabbing item like a parrot from the New World. Cities like Boston and Charleston, where a parrot might be sold, were much smaller in those days, and pirates were often well-known and hunted criminals who would have a hard time entering the waterways of more populous cities like London.

Konstam also noted one account from the early 18th century when William Dampier, a British explorer, noted that the best parrots came from near Vera Cruz, a coastal region of Mexico. Pirates may have changed but humans have not. Vera Cruz remains a hotspot for the illegal parrot trade, a place where thousands are illegally poached each year.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook