The World’s First Travel Writer Was a Guy From Ancient Greece

You can thank second-century geographer and writer Pausanias for travel literature.

An 1819 painting of ancient Livadeia, a city “no less adorned than the most prosperous of Greek cities,” wrote Pausanias. (Photo: Public Domain)

In ancient times, tourists and travelers in Greece have gotten into some pretty intense situations. An adventure-seeking traveler would bathe in the river Herkyna, then consume sacrificial meat, wander through a dark cave of Livadeia to seek out the oracle, and emerge “paralyzed with terror and unconscious both of himself and of his surroundings.” And that’s just a one-day itinerary.

So wrote Greek geographer Pausanias, one of the very first travel writers, in his second-century book Hellados Periegesis, or Description of Greece. As the oldest and most detailed travel guidebook uncovered from ancient times, it is often considered the guidebook that started the genre of travel literature we know today.

“There were similar guides, but they were much smaller,” says Maria Pretzler, professor of ancient history at Swansea University in Wales and author of Pausanias: Travel Writing in Ancient Greece. ”[Pausanias’ writing] was definitely the biggest and most comprehensive from antiquity.” His 10-volume book, she says, is “the oldest travel guide that still works.”

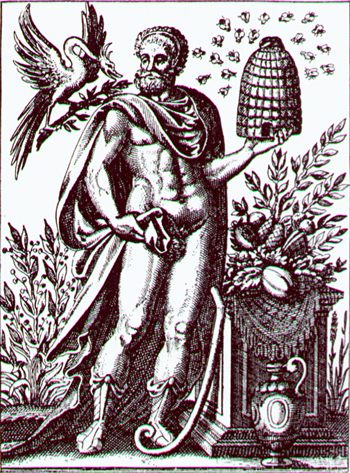

Trophonius’ temple was at the oracle. “The most famous things in the grove are a temple and image of Trophonius,” wrote Pausania. (Photo: Public Domain)

You can find Pausanias’ descriptions from the series sprinkled in just about every travel guide to Greece. Pretzler, for example, hasn’t found a travel guide that doesn’t refer to Pausanias’ account of the oracle in a grove at the ancient capital of Livadeia—a now barren site no one would ever know about had it not been for his writing.

Each of the 10 books details a particular region of Greece. Pausanias describes dozens of cities, from Athens, Olympia, Delphi, to Mycenae. He even trekked up steep mountain roads to visit the more isolated, small villages. The entire Description of Greece took Pausanias at least 20 years to research and complete. Like the authors of modern culture guidebooks who write about the essential artworks and landmarks to visit in a foreign city, Pausanias points out to travelers, scholars, and excavators throughout time what is worth seeing in Greece.

A map of Greece outlining which parts of the country is described in each volume of Description of Greece. (Photo: Tomisti/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Very little is known about Pausanias’ personal life, but it is believed he hailed from a wealthy family in Lydia in Asia Minor, which is modern-day Turkey. Pausanias was a well-educated man, whose family must have been able to afford to send him to larger cities for his education.

“Traveling was done on a grand scale, so it was quite expensive,” says Pretzler. “They have quite the entourage, with a carriage drawn by oxen, and pack animals. You have to imagine when Pausanias rides into one of these tiny towns in the Peloponnese mountains it would have really been the kind of event where the whole village comes together.”

While his book focuses on his tour of mainland Greece and the Peloponnese peninsula, Pausanias also traveled to Egypt, Italy, and the Middle East.

A painting of the pillars of the temple at Karnac in Thebes, Egypt, a poor city according to Pausanias. (Photo: Wellcome Library, London/CC BY 4.0)

Since the traveling was done by foot or by carriage, Pausanias most likely stayed overnight at the towns and cities he visited. He spoke with locals to document the history of the town, noting myths, monuments, art, statues inscribed with laws, and events—such as the ancient Olympic games. The roads were rocky and he would sometimes indicate that a traveler would need to be a fit walker to scale up mountain paths to reach some of the secluded temples.

By the second century AD, Greece was firmly under the control of the Roman Empire, and there were only a few more years of ancient culture left, explains Pretzler. Both Greeks and Romans revered ancient Greek culture, and still wanted to know about the cities mentioned in Homer’s epics and Herodotus’ histories. Pausanias’ writing may have been a means to document and share those cities. But in the ancient world, there was no such thing as a travel guide yet. Without a definitive genre for his books, it’s uncertain how Pausanias intended Description of Greece to be used and who his exact audience was.

“It’s probably either he wants people to read it and basically travel in their heads, because Greece is the country that people read about in all the earlier texts that were the most popular books at the time,” reasons Pretzler. “Or, he wants people to read it in advance of their trip or perhaps they take it on their trips.”

Sounion, home to the temple of Poseidon, begins Pausanias’ guide. (Photo: Miltos Gikas/CC BY 2.0)

Sounion, home to the temple of Poseidon, begins Pausanias’ guide. (Photo: Miltos Gikas/CC BY 2.0)The books are difficult to read. His language is highly detailed and “almost pious,” Pretzler says, explaining that he deliberately wanted to sound like a serious academic who spent 20 years gathering accurate information.

“He doesn’t give you any practicalities,” says Heinrich Hall, an archeologist who often refers to Pausanias while he gives tours of Greece with Peter Sommer Travels. “He doesn’t tell you where to stay, where to eat, how long to stay somewhere. His focus is what you should pay attention to when you’re there—what is worth seeing.”

Unlike Yelp, TripAdvisor, or Lonely Planet, Pausanias doesn’t give detailed advice or reviews, like whether you should eat the olives in Olympia or try the wine in Mycenae, says Hall. Rather, Pausanias provides insights on culture, and local beliefs and traditions that have been crucial in art history. Here, he shows his knowledge of artists’ styles:

“There is also a sanctuary of Apollo which is very old, as are the sculptures on the pediments. The wooden image (xoanon) of the god is also ancient; it is nude and of a very large size. None of the locals could name the artist, but anyone who has already seen the Herakles of Sikyon would assume that the Apollo of Aigeira is a work by the same artist, namely Laphaes of Phleious.” (7.26.6.)

It is surprising the buildings he excludes or doesn’t describe in detail, such as the Parthenon in Athens. It’s perhaps one of the most famous buildings in Greece, yet his description is lackluster and rather casual, says Hall. (Photo: Neokortex/CC BY 3.0)

It is surprising the buildings he excludes or doesn’t describe in detail, such as the Parthenon in Athens. It’s perhaps one of the most famous buildings in Greece, yet his description is lackluster and rather casual, says Hall. (Photo: Neokortex/CC BY 3.0)Archeologists even flipped through his books while completing the first major excavations of Athens, Delphi, and Olympia. In the early and mid 19th century when English lords traveled on their grand tours, they would bring the appropriate volumes of Pausanias’ for their stop in Greece, Hall says. Like those 19th-century travelers, Hall carries the relevant books of Pausanias with him when he leads tours of Athens and in the Peloponnese, reading out sections to his group.

“We actually take him and quote him directly because he describes the appearance of buildings that aren’t standing anymore,” Hall says. “Rather than paraphrasing, we have the opportunity to directly quote him, which brings the second century character as a speaking voice into our tours.”

Many tour guides of mainland Greece will turn to Pausanias automatically or unknowingly, says Hall. In addition to the monasteries and temples that remain in ruins, Pausanias also preserves the people in his texts.

“If you look at modern travel writing we tend to be much more interested in what people say about people than what people say about things,” he says. “He produced something that in its context and in its time as far as we know is unique.”

An 1829 copy of Pausanias Description of Greece. The books were carried by many travelers during the 19th century. (Photo: Public Domain)

It wasn’t until the 19th century that people began writing travel guides again and started to shape and establish the genre. Some of the very first guidebooks were written about Greece, and they were essentially an update on what Pausanias had written, says Pretzler. “If you have the Blue Guide to Greece, which is very focused on the cultural stuff like Pausanias, you get pretty large chunks of [his work] paraphrased and sometimes quoted.”

Some scholars and adventurers have made itineraries based on his descriptions independently, establishing a 21st-century version of the “Pausanias tour.” It may be almost 2,000 years later, but the pioneering writer’s travel tips live on.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook