Australia’s First Published Dictionary Was Dedicated to ‘Convict Slang’

The “flash” language reflected the makeup of the British penal colony at the time.

On February 25, 1832, the Sydney Monitor reported an arrest for illegal gambling, but not in so many words.

Four men—Thomas Cheesman, John Drew, Michael Reardon, and John Webster—were apprehended on Bathurst Street for tossing halfpence coins from a wooden plank, and placing bets on which would land on heads and which on tails. They were “spinning the mags,” the arresting officer, one Constable Sutland, told those assembled in the courtroom later, according to the unusually detailed newspaper account. “What do you say?” asked Captain Rossi, understandably puzzled. “I don’t understand you.”

Constable Sutland then explained, “in a manner truly impressive and edifying to both Bench and bye standers, and with much historical tact” that “spinning the mags, your worship, is slang for toss-half penny,” a more common name for the game of chance they were playing. The details of the crime sufficiently clear, the men were jailed for a week.

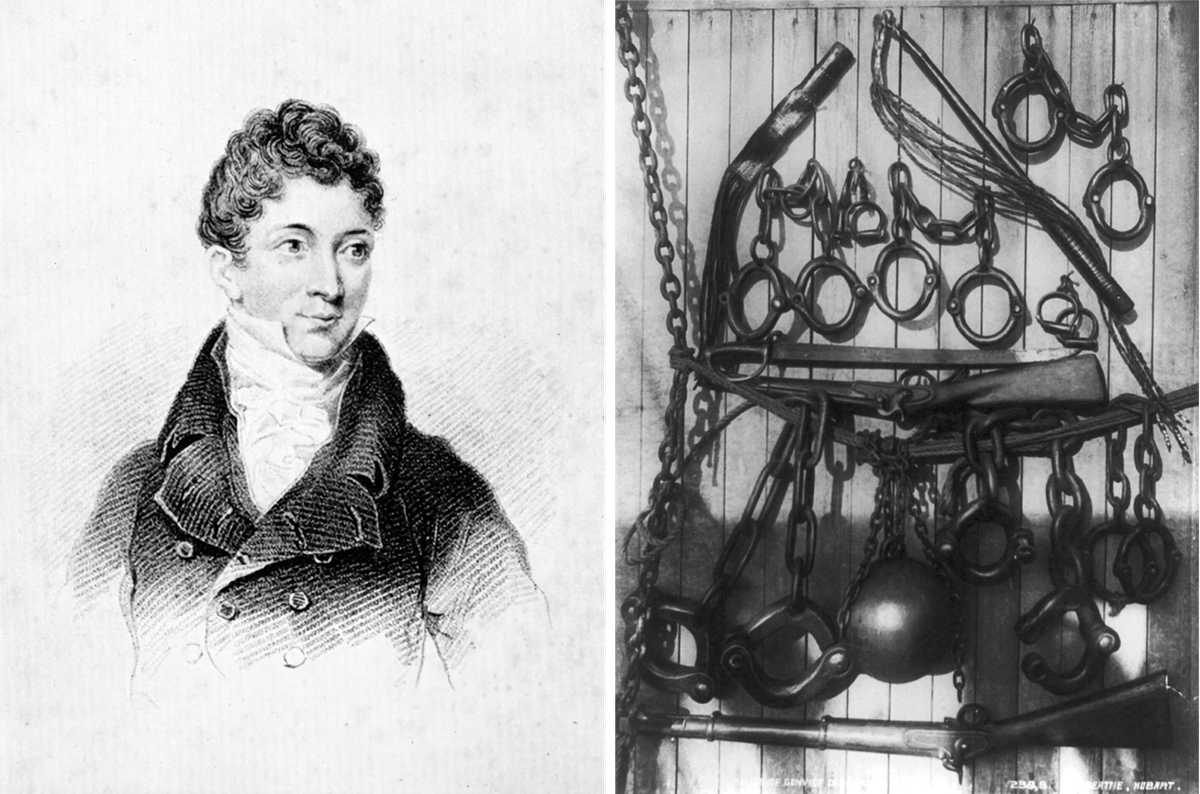

There’s no way of knowing whether Constable Sutland had his own copy, but a special dictionary had, in fact, been published some years earlier for just this kind of scenario. James Hardy Vaux’s Vocabulary of the Flash Language, typically regarded as the very first dictionary produced in Australia, translated into plain English some 700 slang terms regularly used by people engaged in illegal activity. Vaux translated this “flash” language while himself imprisoned at Newcastle, in southeastern Australia. He even dedicated the book to his supervising commandant.

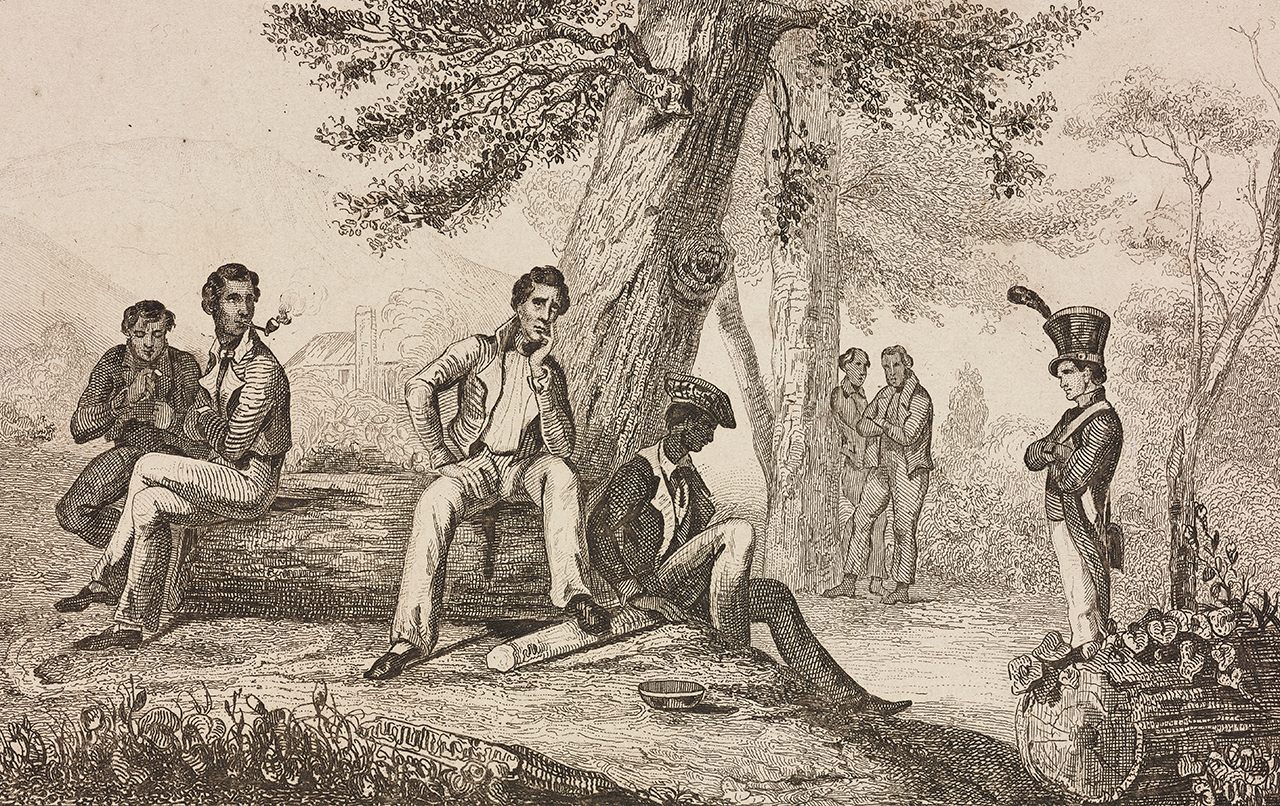

Between 1788 and 1868, more than 160,000 people were transported from England, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland to the opposite side of the world to serve their time in Australia, help establish a new outpost of the British Empire, and generally no longer be in the British Isles anymore. It was an anxious time, with the disruption of the Industrial Revolution driving a rise in petty theft. The state managed the turmoil, in part, by instituting forced transportation to the colonies—often for minor infractions, if there were infractions at all. Many of those transported, in fact, were political prisoners.

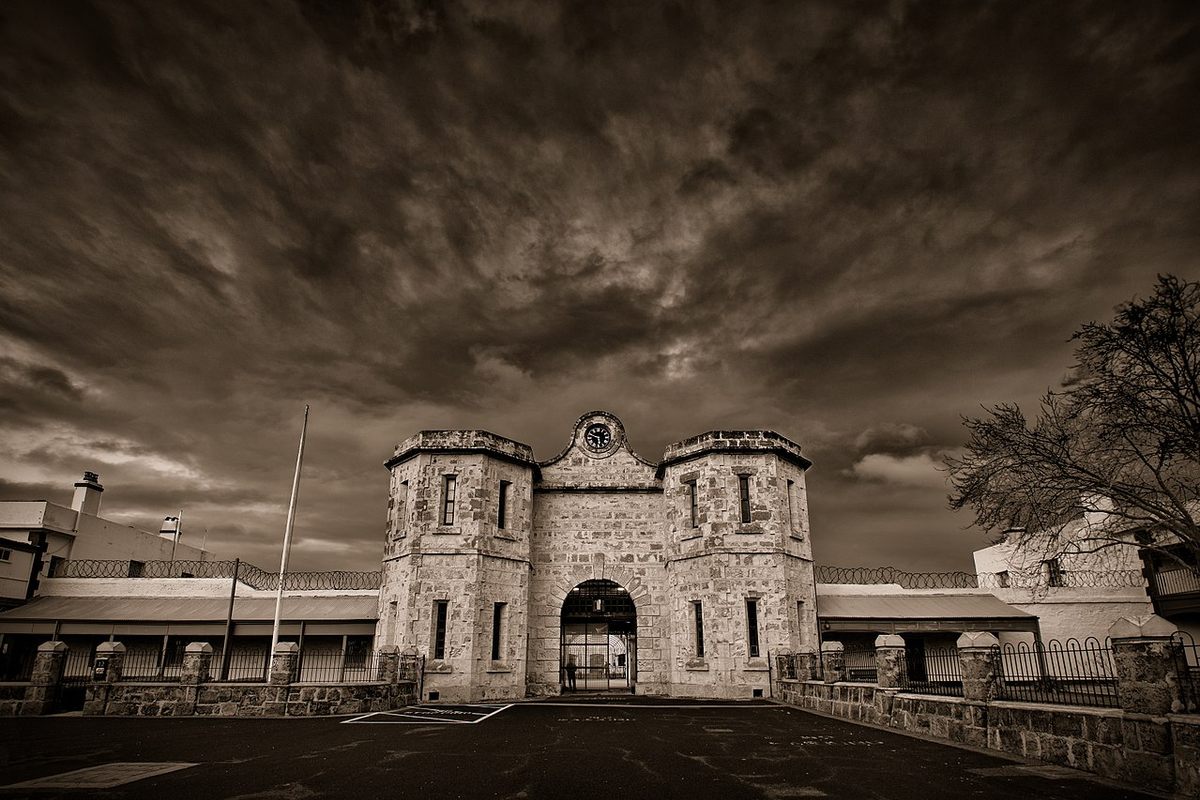

Once the American Revolution put an end to transportation there, Australia became the primary destination. Those put on the ships ended up in places such as the Port Arthur Penal Station in Tasmania, the Hyde Park Barracks in Sydney, and Fremantle Prison near Perth, among many others. Once notorious for their awful conditions and hard labor, a number of these sites are now museums of Australia’s “convict period.” Visitors can glimpse that past in relics ranging from a gallery of prisoners’ tattoos to an unconsecrated “Convict Church.”

The influx of incarcerated persons not only brought more European people to Australian shores, but also variations on the English language. What Vaux called “flash” language was also known as “thieves’ cant,” an extensive set of code words that had flourished on the margins of English society for centuries. (“Flash,” in other words, is flash for “cant.”) Scholars agree that the cant itself did not really evolve into a specifically Australian version, and Vaux’s publication followed centuries of older cant dictionaries produced in England. What set Vaux’s apart, however, was its unique utility in the Australian setting.

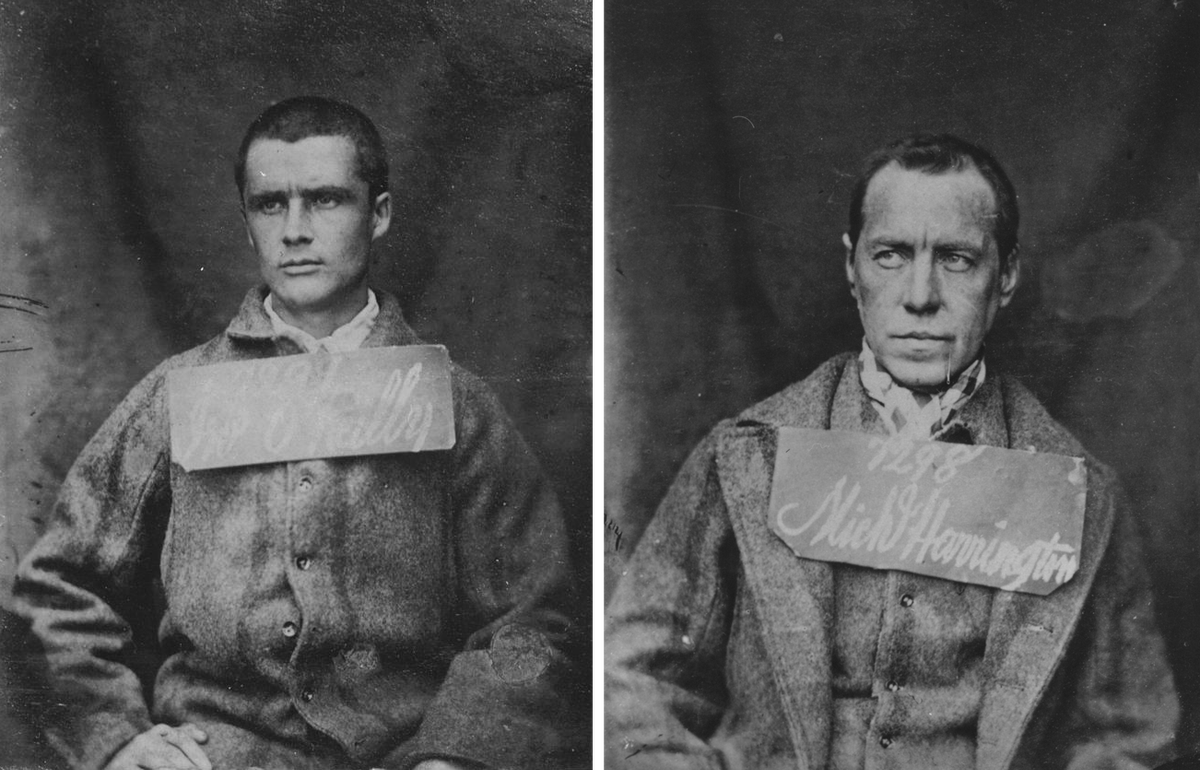

Nineteenth-century Australia was a flash paradise teeming with accused outlaws, former outlaws, and people who knew outlaws—so it follows that officials, policemen, and others would want to be familiar with the argot all around them. According to a paper by A.L. Beier, a scholar of cant and retired historian from Illinois State University, 75 percent of New South Wales’s population in 1819 (when the dictionary was published) was “either current or former convicts or their descendants. By 1828, the proportion had risen to 87 percent, and while it declined thereafter because of free immigration, it still stood at 59 percent in 1851.” And that was just New South Wales, the region of the Australian mainland that includes Sydney and Newcastle. Population data for the island of Tasmania, meanwhile, distinguished between recent arrivals and the Aboriginal people who had lived there for millennia (and tended to stay away from colonial settlements). In 1822, Beier writes, 58 percent of Tasmania’s non-Aboriginal population had criminal convictions. Vaux himself had been transported to Australia on three different occasions, and served some of his time in the Hyde Park Barracks.

Recently, to mark the dictionary’s 200th anniversary, the Australian writer and illustrator Simon Barnard published an updated version of Vaux’s text, featuring historical examples of the terms’ usage in court and criminal records, and, eventually, the assimilation of certain words into the mainstream. Barnard says that one of the most striking patterns in his research is the degree to which criminal justice officials could not understand any of what they were told by defendants. According to Beier, special cant interpreters were called into the courts of New South Wales beginning in the 1790s.

Barnard found documented examples of words that had to be translated in court, such as “buzzman” (“Buz-Cove” or “Buz-Gloak” in Vaux’s dictionary), meaning, simply, a pickpocket. That was general, while other terms were maddeningly specific. Consider “cat and kitten rig,” for the practice of “stealing pewter quart and pint pots from public-houses.” Cant was so important—and so elusive—to the justice system that some defendants used their fluency to lighten their sentences. After John Farrell, Thomas Hopkins, and George Lyons robbed a “panny” (a house, per Vaux) in 1786, Farrell explained to the judge that “panney is the meaning of the house,” and was spared the death sentence issued to his codefendants.

Today, Farrell would probably be called a “snitch”—but only because the word has moved from thieves’ cant into our common parlance. “To impeach, or betray your accomplices,” writes Vaux, “is termed snitching upon them. A person who becomes king’s evidence on such an occasion, is said to have turned snitch …” It’s hardly the only word from Vaux’s dictionary to have escaped the argot over time. A January 28, 1833, crime report in the Sydney Herald referred to the arresting officer as “the Charley” (a watchman in Vaux), and then stated that the arrested, one Mary Malone, tried “bonnetting” the officer (making false excuses to him) before ultimately “bolting” (well, you get it).

In the introduction to his updated text, Barnard lists several other words from the dictionary that have persisted, specifically in Australian English: “Danna” (excrement) helped give way to “dunny” (toilet), “togs” (clothing) has become slang for swimwear, “ridge” (gold) is preserved in “ridgy-didge” (Aussie for good or genuine, according to the Oxford English Dictionary). And there was at least one cant term unique to the Australian variety, and inextricably tied to the landscape itself. “Bush’d,” defined by Vaux as “poor; without money,” comes from escapees and formerly incarcerated people who fought to survive in the wilderness—what Australians call the “bush,” according to Therese-Marie Meyer, a scholar of Australian convict history at Germany’s Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg. If you look closely, you might even find some cant on walls surviving from colonial Australia: According to Barnard, the words “Grog for Me”—“Liquor for Me”—are still visible, etched onto a wall in Bothwell, Tasmania, near the name of the likely scribe, William Bray. Once a prison, that Bothwell building is now a private residence, and Barnard says that most convict-era graffiti consists of pictures rather than words.

To be sure, many cant terms have also been lost to time, and encountering them today in Vaux’s dictionary suggests a kind of subversive poetry too rich to have ever been real. While compiling his updates to Vaux’s text, Barnard came across a few particularly beguiling examples; his favorites include “resurrection-cove,” or someone who stole bodies from graves, and “morning-sneak,” an early-day act of thievery executed “by slipping in at the door unperceived, while the servant or shopman is employed cleaning the steps, windows, etc.”

Simply uttering these words—really anything the police couldn’t understand—could put one at risk of arrest. Barnard details an 1845 case, for example, in which a pair of suspects would have evaded the police had a passerby not heard the men using flash language, prompting the cops to take another look and, ultimately, re-incarcerate the men at Hyde Park Barracks. Likewise, when James Gavaghan was overheard muttering about a “chiv” (now a common term for a makeshift knife), he got himself two years at Port Arthur. A January 16, 1832, listing of police incidents in the Sydney Herald was explicit, reporting that one Mary Connor was institutionalized for a month after “throwing all the hard words in Hardy Vaux’s dictionary at her mistress’ head …”

According to Meyer, cant is a “sociolect”—a variety of a language spoken by a particular social class—rather than a dialect tied to a specific region or location. One of Vaux’s terms, in fact, is “family,” a title he gave to all “who get their living upon the cross,” or through illegal activity. These examples illustrate the fear that authorities and the non-flash speaking public had of flash or cant—that it not only facilitated crime, but also inspired it. The policies of some Australian prisons, says Barnard, addressed this fear by condemning the incarcerated to total silence. (That carceral method wasn’t pioneered in Australia, he adds; it had previously been practiced in Philadelphia.)

At the same time, that perception may be part of what gave cant or flash such currency among those who spoke it. Beier cites people who complained at the time that cant “played a role in fostering solidarity among convicts,” and who noted that incarcerated laborers “‘have a strong esprit de corps, which is kept up by their speaking a language so full of cant expressions as to become a separate dialect.’” It was, in its way, an instrument of resistance—an expression of identity and self-determination among those who had lost their freedom, often for little or no offense, and been forced across the world.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook