The ‘Darting Children’ That Helped Japan Win Its War on Traffic Accidents

How hand-painted signs known as Tobita-kun became beloved local mascots.

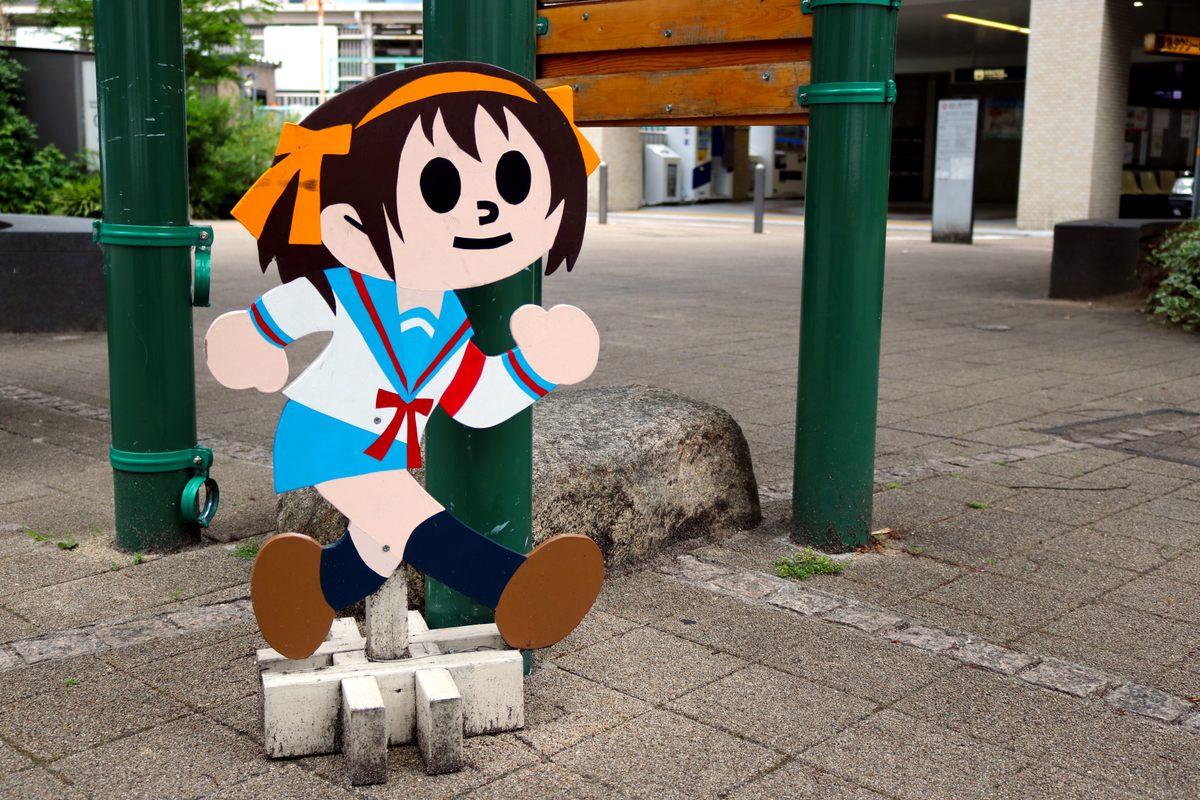

Everyday on the sides of streets across Japan, from major urban intersections to sleepy rural roads, stand young children, poised to dash out into traffic. But Tobita-kun, the name by which the children are commonly known, never actually makes it out onto the road. These “children” are, in fact, a style of wooden sign that for the last half-century has served as a warning to the nation’s drivers to watch for flesh-and-blood children who may unexpectedly dart into traffic, particularly in school zones. Often charmingly handmade by local councils, Tobita-kun has become an icon on Japan’s roadways—and played a role in revolutionizing road safety in the country.

In the years following the end of World War II, Japan’s rapid economic recovery was not without challenges. Across the country, pedestrian and motorist fatalities accumulated at a rapid clip through the 1960s, a period known locally as the “Traffic War.” During this time, one commentator noted, road fatalities exceeded those of certain actual wars in which Japan had fought.

Indeed, as the National Institute for Land and Infrastructure Management (NILIM) reported, in 1970 there were 16,765 fatal road accidents recorded nationwide—a rate of 16.33 per 100,000. (The United States, by comparison, registered a rate of 26.8 per 100,000 in 1970, but no war was declared.)

Out of the chaos, however, came an enduring—even beloved—cultural icon. Never officially named, Tobita-kun—or, more formally, Tobidashi-bouya—is known by similar names depending on the region, all generally translated as “jumping out boy.” Indeed, it is common for the phrase tobidashi chuui—“Watch out for darting children”—to be emblazoned across the wooden figures.

Tobita-kun’s design has taken on many forms over the decades. Structurally, the signs are commonly made of wood cut into the shape of a small, cartoonish child, often depicted mid-stride. Ready-made plastic versions are available in stores (North America has an occasionally seen a yellow plastic version of its own), although Japan’s extensive network of local volunteer safety councils continue to craft and paint wooden versions by hand.

The classic design—dubbed ”Series 0” by artist Jun Miura—was created in June 1973 by signmaker Yosei Hisada of Higashiomi in Shiga Prefecture, at the request of the town’s Social Welfare Council. In this version, Tobita-kun is striding straight into traffic, with a bright shirt and vintage hairstyle.

Fifty years later, Hisada and his son, Akihiro, still produce classic Tobita-kun signs for local parent-teacher associations, travel organizations, and business clients who request custom designs.

On a recent visit to the Hisada signmaking shop in Higashiomi, the workshop was stacked with Tobita-kun signs drying between stages of the involved painting process. “We still make about 500 signs each year,” says Akihiro Hisada.

The 50th anniversary of Tobita-kun is cause for celebration in Higashiomi. Spokesperson Ai Kawamoto says in an email that the town has launched a commemorative website, and is planning events to mark the anniversary.

Series 0 signs are far from the only design in use, however. Others, such as those found in Hiroshima, feature designs with an upstretched hand, in the manner of the way schoolchildren in Japan are taught to cross the street, known as the Wataruyo (“I’m Crossing”) sign.

Indeed, as the classic Series 0 signs spread throughout Japan in the 1970s, countless regional variations popped up, usually featuring Tobita-kun wearing a locality’s traditional dress, such as the signs around Koka, decorated in recognition of the city’s role as a historic ninja training ground. Others feature famous figures from Japanese animation and pop culture, including one paying homage to the distinctive look of manga author and illustrator Jun Miura (long hair and sunglasses).

Another notable variety is the Genki-kun style found in Ishikawa Prefecture. The mascot of a 1991 prefectural sports tournament, Genki-kun now endures as a symbol of traffic safety. The spread and longevity of these signs can be attributed to the efforts of one man, 82-year old Jiroku Yamagishi.

Yamagishi, of the small city of Nanao, began handmaking the signs after his mother was struck and killed in a traffic accident. “I want the number of people affected by accidents to decrease,” he said in an interview this year with Japanese media. Turning out more than 1,200 of the two-foot signs to date, Yamagishi donates them to boards of education and city offices in the area. “As long as I’m fine, I want to keep making signs,” he said.

To explain the ongoing popularity of Tobita-kun, Japanese pop culture expert Taylor Atkins of Northern Illinois University cites the machi zukuri, or “town building” initiatives of the 1970s, designed to foster local identity and community pride. “In some ways, [Tobita-kun] are akin to the municipal mascots … that so many towns and cities now have to promote and distinguish themselves,” Atkins says in an email.

Atkins also notes the popularity in Japan of using cartoons to disseminate information to the public. “Earthquake preparedness instructions and many other public service messages are now distributed in cartoon formats,” he says.

Higashiomi spokesperson Kawamoto attributes Tobita-kun’s staying power to the “silver ratio” design aesthetic popular in Japan, shared by other beloved characters such as Hello Kitty and Doraemon. “Companies and individuals [also] order custom-made signboards based on the Series 0 design,” Kawamoto adds.

Asked for his opinion on the popularity, signmaker Hisada gestures to a stack of drying kun signs and says, “Well, he’s cute, isn’t he?”

While Tobita-kun reflects Japan’s efforts toward traffic safety, and is undoubtedly an iconic figure, the direct impact of the signs is unknowable. Asked about their impact, a spokesperson for the Japan Automobile Federation noted “[The JAF] has not formally investigated the effect,” and cannot definitively quantify their impact.

Indeed, Tobita-kun seems to be one of many factors that helped decide Japan’s traffic war. Other factors could include the introduction of high-speed shinkansen bullet-trains, and ubiquitous local rail networks in general, which lessened reliance on cars. As Bloomberg’s David Zipper noted, as a result of extensive, functional rail networks, “driving in Japan becomes an option, rather than a necessity.”

Lighter, lower-powered subcompact vehicles, known as keijidousha, or “kei cars,” are another possible reason, in stark contrast to North America’s preference for ever-larger vehicles. Japan also has some of the world’s toughest drunk-driving laws, and the number of traffic signals increased from approximately 15,000 in 1970 to more than 200,000 by 2013.

Public safety campaigns for motorists are also common. “On a nationwide and ongoing basis, we are implementing a project called ‘Omoiyalty Drive,’” writes the JAF spokesperson in an email. Translated approximately as “compassionate” or “thoughtful” driving, the initiative is described as a “caring project” designed to reinforce patience, good manners, and traffic etiquette among motorists and pedestrians.

Combined, the measures have been effective. Road fatalities in Japan have declined to just 25 percent of peak 1970 figures, according to the NILIM.

As an indelible part of Japan’s motoring landscape, Tobita-kun will continue to almost dart into traffic and serve as a reminder for drivers to stay aware of their surroundings—not just the road, but the local town that they happen to be driving through.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook