The Forgotten Trans History of the Wild West

It was a frontier in more ways than one.

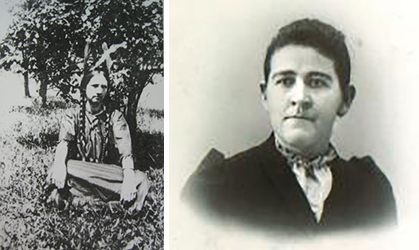

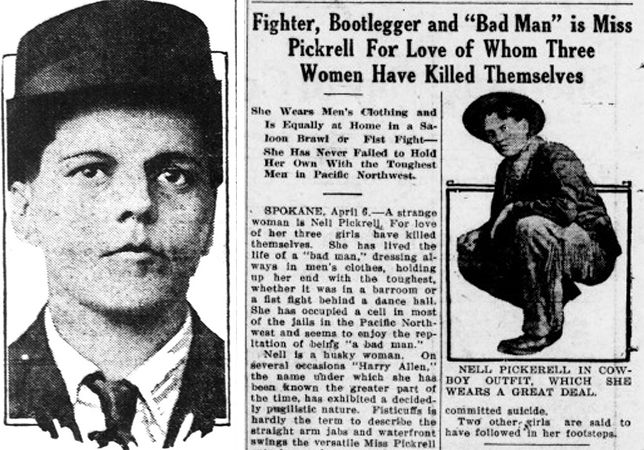

From 1900 to 1922, Harry Allen was one of the most notorious men in the Pacific Northwest. The West was still wide and wild then, a place where people went to find their fortunes, escape the law, or start a new life. Allen did all three. Starting in the 1890s, he became known as a rabble-rouser, in and out of jail for theft, vagrancy, bootlegging, or worse. Whatever the crime, Allen always seemed to be a suspect because he refused to wear women’s clothes, and instead dressed as a cowboy, kept his hair trim, and spoke in a baritone. Allen, who was assigned female at birth, was actually far from the only trans* man who took refuge on the frontier.

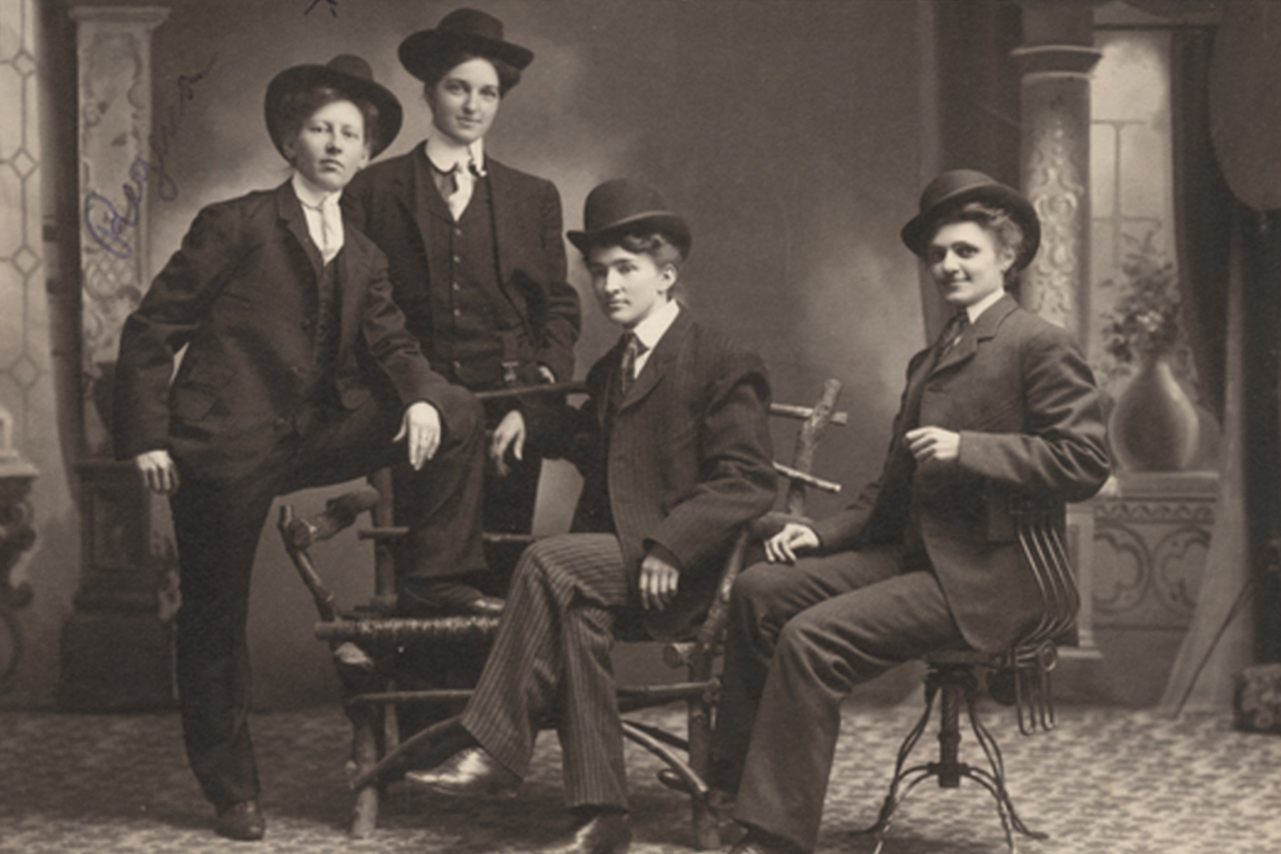

Despite a seeming absence from the historical record, people who did not conform to traditional gender norms were a part of daily life in the Old West, according to Peter Boag, a historian at Washington State University and the author of Re-Dressing America’s Frontier Past. While researching a book about the gay history of Portland, Boag stumbled upon hundreds and hundreds of stories concerning people who dressed against their assigned gender, he says. He was shocked at the size of this population, which he’d never before encountered in his time as a queer historian of the American West. Trans people have always existed all over the world. So how had they escaped notice in the annals of the Old West?

Boag expanded his research beyond the Northwest, but limited it to towns west of the Mississippi, and the period of time from the California Gold Rush through statehood for all the Western continental territories. It wasn’t that this time and place was more open or accepting of trans people, but that it was more diffuse and unruly, which may have enabled more people to live according to their true identities, Boag says. “My theory is that people who were transgender in the East could read these stories that gave a kind of validation to their lives,” he says. “They saw the West as a place where they could live and get jobs and carry on a life that they couldn’t have in the more congested East.” Consider Joseph Lobdell, born and assigned female in Albany, New York. When he surfaced in Meeker County, Minnesota, he became known as “The Slayer of Hundreds of Bears and Wild-Cats.”

In 1912, Allen was arrested in Portland, on the charges of “white slavery,” as he had traveled across state lines with a woman named Isabelle Maxwell, a sex worker who was posing as his wife. In reality, Maxwell was Allen’s partner, and the two had fled across the region to stay one step ahead of the law. Portland police sentenced him to 90 days in jail for “vagrancy”—one of those vague charges that stood in for gender non-conformity.

This opportunity for reinvention seemed to be particularly available to people assigned female at birth who lived their lives as men. In a 1908 interview with The Seattle Sunday Times, Allen articulated his discomfort with his assigned sex. “I did not like to be a girl; did not feel like a girl, and never did look like a girl,” he said. “So it seemed impossible to make myself a girl and, sick at heart over the thought that I would be an outcast of the feminine gender, I conceived the idea of making myself a man.” Allen’s identity fascinated local papers, which cast it as part of the zeitgeist of the American frontier. One publication framed him among “the scum of the West” for his active career of saloon brawling, bootlegging, bronco busting, and horse stealing. The press gawked at his swagger, foul mouth, and penchant for hard drink. Allen found near-infinite possibility in men’s attire, and worked as a bartender, barber, and longshoreman.

From 1880 to 1930, Seattle’s population ballooned from around 3,500 to more than 350,000, a testament to the opportunities the town presented. According to Boag, local papers offer some of the most thorough, extensive records of people who were likely trans on the frontier. Naturally these publications lacked the language or understanding of gender we have today, and the papers paid their bills with sensation, scandal, and shock. So they got a lot of mileage out of encounters between “civilized” society and gender non-conforming individuals.

Allen’s identity was notable for how public it was. On the other hand, many trans people lived out their lives without drawing the attention of local papers. In Boag’s research, a trans person’s assigned sex was most likely to be discovered upon death or serious illness. When 80-year-old lumberjack Sammy Williams died in Montana in 1908, the undertaker discovered his assigned sex, dumbfounding the community that had only ever known him as a man.

It was easy for tabloids and historians of the time to explain away trans men as a quirk of the frontier. It was, after all, a land dominated by men: violent, physically demanding, and steeped in the oppression of women. It seemed logical that certain women might choose to disguise themselves as men for safety, or to gain access to power and agency—with no queer motive. “If people thought you were a man, you wouldn’t be bothered or molested, there’s good evidence that some women dressed as men to get better paying employment,” Boag says. The best job most women could hope for in the Old West was cooking or housekeeping. On the other hand, someone assigned female at birth who passed for a man could earn real wages.

In the 1870s, Jeanne Bonnet, who was assigned female at birth, was arrested several times in San Francisco for dressing like a man. Though Bonnet explained this sartorial choice as a career choice—they worked as a frog catcher, a job that simply could not be done in a dress—they wore men’s clothing throughout their life, suggesting a motivation more personal than a paycheck.

This idea—among others—that a person might assume another gender identity for purely practical reasons, is part of the reason that there is little explicit record of a queer history of the Old West, and says almost nothing about those people assigned male at birth who lived their lives as women. Trans women had little safety or comfort to gain by living as women, and Boag encountered far fewer of their stories in his research. Consider the case of the woman only known by a married name, Mrs. Nash. Born in Mexico and assigned male at birth, Nash worked as a laundress for the Seventh Cavalry in Montana for over a decade, during which time she married three different enlisted men.

When Nash died of appendicitis in 1878, the woman preparing her body for burial discovered her assigned sex. In the months following, national papers covering her case claimed she had always been seen as an outsider of suspect gender, but eyewitness accounts collected in the Bismarck Tribune described her as a respected woman, interior decorator, midwife, and prized tamale cook who was a core part of the Fort Lincoln community. Nash, who was Mexican, also had her race cited as a way to cast doubt on her character, according to Boag. This wasn’t uncommon, as racialized descriptions were connected with a kind of effeminacy, at least in the case of trans women.

As the West changed, so too did its apparent prevalence of non-conforming dress, which could not coexist with settled, civilized America. “As the frontier closed and the Wild West disappeared, these people who found a life there, found validation there, also disappeared from our history,” Boag says. Now, the Pacific Northwest pays homage to its trans forebears in the Museum of Trans Hirstory & Art (MOTHA), a series of events and installations—a fittingly transient existence when considering the wandering nature of Allen and others. Chris E. Vargas, a trans man who lives in Bellingham, Washington, created MOTHA after confronting the huge gap of knowledge between the Pacific Northwest’s well-covered gay history and less-researched trans history, he said in an interview with Seattle Weekly.

The one thought that has stayed in Boag’s mind throughout his research was the sheer resilience of the trans people who struck out for a life on the frontier. In particular, he felt drawn to the case of Alice Baker, who was assigned male at birth and worked as a schoolteacher in Harrah, Oklahoma. After someone reported her to the police, she traveled to a number of places (Segundo, Colorado; Portland, Oregon; Kansas City, Kansas) until she was caught, each time starting anew with an arsenal of names (Alice, Mabel, and Madeline Baker, and Irene Pardee). These encounters with the law, however, did not seem to stop Baker from living as her true self. In her time on the lam, she received marriage proposals from several evangelical ministers and a lawyer, the latter of whom she married. Before Baker dropped off the map in 1913, she had traveled to Japan, where she and her husband sold counterfeit bills for gold. “I had the evidence that, place after place and year after year, she survived,” Boag says. “She was clearly someone who really struggled and succeeded despite all the setbacks that came with being herself.”

* As the term “transgender” did not emerge until the late 20th century, it was not a category these people would have used themselves, writes Emily Skidmore in True Sex: The Lives of Trans Men at the Turn of the Twentieth Century. But Skidmore sees trans, rather than transgender, as a helpful umbrella term to acknowledge and encompass the gender variance expressed by historical individuals, and so we use the same terminology in this article.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook