Inside One Family’s Mission to Revive an Abandoned Appalachian Trout Farm

The Walkers’ hatchery now provides rainbow and brook trout to Michelin-starred restaurants across the East Coast.

Ty Walker squats on the grassy banks of a 150-foot-long, 10-foot-wide earthen pond lifting a net filled with thrashing young rainbow trout from the churning spring water. He nudges a pair of curious Great Pyrenees away, then carefully drops a dozen fish into a large bucket of water and hoists it onto a scale for his wife, Shannon, to log the results in a notebook.

“We’re calculating average weights to get a bead on how fast the fish are growing and when they should be ready to harvest,” says Ty. It’s also an opportunity “for a health checkup.”

The monthly survey takes about a day and involves netting 10 sample groups from each of the Walkers’ seven ponds and five concrete raceways. Together the impoundments hold three species and more than 20,000 trout at various stages of development. Ty and brother-in-law Matt Wagner hand-harvest and process about 400 16-inch fish a week—a size that takes about a year for rainbows and up to two years for brook trout to reach. They’re then packaged, placed in coolers, and shipped overnight from the Walkers’ farm in Virginia to top East Coast fine-dining establishments like the two Michelin–starred Blue Hill at Stone Barns in New York.

“Beyond shipping, we do everything the old-fashioned way, like they did back in the 1930s,” says Ty. “It’s a lot of work, but it’s the only way you can consistently raise fish that taste like you pulled ’em right out of a mountain stream.”

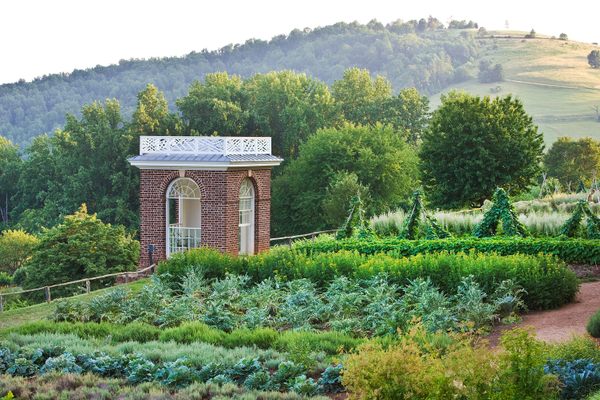

The method works because the Walkers’ Smoke In Chimneys fish farm is actually a restored 1930s U.S. Department of Interior trout hatchery and research center that sits in the Blue Ridge Mountains on the edge of the George Washington & Jefferson National Forest.

Here there are no electric pumps, water filters, aquaculture tanks, mechanical agitators, antibiotics, oxygen monitors, or chemical additives. Impoundments are gravity-fed by water from an artesian spring that surges from the limestone bedrock at a rate of 2,000 gallons a minute. Swift-flowing, two-foot-deep raceways mimic currents in steep mountain streams and help fish develop strong musculature. Packed, flow-through, shale-bottom ponds lined with aquatic plants, grasses, pollinator gardens, and nearby forests act as living ecosystems replete with naturally occurring microbes, insects, amphibians, and crustaceans. The au naturel diet is supplemented by top-shelf feed from Canada.

“I’ve been a chef for 20 years and eaten tons of [freshwater] fish,” says Patrick Pervola, research and development chef at the Michelin-starred Washington, D.C., restaurant Albi. He and boss Michael Rafidi—a James Beard 2024 Outstanding Chef award finalist—buy about 120 Smoke In Chimneys trout a week. They like to pan sear them whole with, say, crab tabouli, blistered asparagus, chermoula, smoked serrano, and amba yogurt. “This isn’t just the best trout I’ve tasted, it’s some of the best fish I’ve tasted, period.”

But while accolades from star chefs have gotten easier to come by, the Walkers’ rise to agricultural stardom was once far from assured.

Ty was raised in the Blue Ridge Mountain foothills of rural Franklin County, Virginia, and introduced to the farm and fishing life by his grandparents.

“They bought a 300-acre farm in the 1970s and made it their primary profession,” he says. Ty remembers summer afternoons spent picking strawberries in a two-acre vegetable garden or fly-fishing for brook trout in nearby mountains. Winters brought tractor rides with grandpa to feed cows. “I appreciate it now, but back then farming was something I had to do, not something I wanted to do.”

Ty went on to study business at James Madison University where he developed dreams of becoming a DJ. Gigs at frat parties and university events inspired a post-grad move to Los Angeles. Relentless cold calls brought work at weddings, film premieres, and, eventually, festivals like Sundance. Five years flew by like a disco-bedazzled fever dream. Then Shannon visited on a 2014 whim, and everything changed.

“We’d become friends during my senior year at JMU and stayed in touch, but when she came out it was just—boom!—head-over-heels,” says Ty.

Shannon was four years his junior and had spent the intervening time in Towson, Maryland, eking out a communications degree as she nursed her mom through what proved to be terminal cancer. She landed a job in corporate marketing and spent two years with Ty in L.A. before the couple married in 2016.

“We were walking on Sunset Boulevard with the traffic, noise, trash … and thought, ‘Is this really how we wanna live?’” says Ty. Long talks unearthed yearnings for a quieter lifestyle centered around nature. “My grandparents were into retirement age, so helping them with the farm seemed like a good start.”

To prepare, they enrolled in a sustainable farming internship with Rogue Farm Corps, based in Eugene, Oregon. The newlyweds spent a whirlwind year working on dozens of partner farms learning to raise hogs, sheep, cows, turkey, and chicken, grow vegetables, and tend orchards.

“The work was grueling and we weren’t making any money,” says Ty. “Shannon took it like a rock star, but I struggled bad.” Still, the takeaways proved worth it: “We learned to eat off the land and realized we loved working with animals more than vegetables.”

The Walkers returned to Ty’s Franklin County family farm in 2017. Within a year they were raising heritage-breed pigs, wagyu-style beef cattle, broiler chickens, and milk cows. Things were chugging along when a real estate buddy called about an abandoned trout hatchery for sale in the 122-person village of Newcastle.

“We went up there mainly out of curiosity,” says Ty. But what they found blew them away. Empty impoundments swallowed by brush behind a rundown farmhouse on a creek were one thing. But an overgrown dirt road leading to a pair of wooden Department of Interior buildings full of old hatchery gear and a large springhouse straddling an artesian spring surging from the exposed bedrock was awe-inspiring.

“I thought, ‘This could be amazing or a financial catastrophe,’” says Ty. Yet after the Walkers meditated under a mature hazelnut tree with their one-year-old daughter, they chose to gamble on possibility.

The family moved in 2019, took jobs in a grocery store to get by, and funneled their savings into a sweeping restoration. They spent months clearing trees, brush, and high grass from impoundments, then borrowed a backhoe to remove decades of mud and detritus. Repairs were made to the farmhouse and outbuildings. Pipes that carried water from the springhouse to the impoundments were excavated from high grass and mud. And the list goes on.

It was a year before they could even consider fish. And that brought more hurdles.

“We couldn’t figure out how to turn on the water,” says Ty. Luckily, inquiries at a local country store brought the help of a hunched octogenarian and former facility employee named Jerry. “He comes out with this four-foot wrench and goes digging through the grass and finds a valve I didn’t know existed. Then he throws the wrench on and tells me to put some ass into it.”

After Ty turned the wrench, water surged through the farm for the first time in decades.

“Jerry grinned and I just hollered for joy,” says Ty. “I’d been struggling to keep the faith and suddenly I knew we were in business.”

But the Walkers weren’t in the clear yet. Internet searches as well as calls to agricultural extension agents and trout farmers in other states for info about gravity-fed facilities turned up nada. Current literature focused entirely on large-scale, high-tech aquaculture or tiny homestead pond systems.

“I was panicking,” says Ty. Then he thought of eBay. And, voila, “I find an out-of-print book that’s part diary, part manual written by an expert researcher back in the 1930s.”

Ty followed it like a bible—and it worked. Still, there was the issue of processing the fish for human consumption. Virtually all of Virginia’s USDA-inspected fish processors are located on or near the Chesapeake Bay, “which is a four-hour drive from our farm,” says Ty.

That’s because the handful of other commercial trout farms in the state are tiny, sell almost exclusively at farmer’s markets, and process their own fish. Most coastal facilities process thousands of fish and shellfish a day, so demand doesn’t justify investment in a new plant in the mountains. And setting up—much less operating—a private processing facility is costly, time-consuming, and labor-intensive. That means, while Virginia is home to 3,500 miles of wild trout streams and brook trout is the state fish, virtually all trout sold within its borders comes from out-of-state aquaculture farms like Carolina Mountain Trout, which sells about 1,000 tons of rainbow trout a year.

The Walkers turned to a USDA-inspected Roanoke community kitchen as a temporary fix to meet their processing needs. But it wasn’t ideal.

“We’d pack our gear, drive an hour, get set up, then rush to finish before the next member came in,” says Ty. “Then you still had to clean up, drive home, unpack, and load the fridges.”

Nonetheless, the stopgap helped the Walkers introduce Smoke In Chimneys to area restaurateurs as they worked to build-out a small, certified kitchen of their own about five minutes from the farm.

“When Ty showed me what they were doing I was stunned,” says chef Tyler Thomas of Roanoke’s River and Rail restaurant. “The fish tasted like it’d been pulled wild from a stream hours before. It was sweet, nutty—just perfect. What they’ve accomplished is next-to miraculous.”

Today Smoke In Chimneys is sold in about 250 restaurants and gourmet eateries up and down the East Coast. These include celebrity chef Patrick O’Connell’s three-star Michelin restaurant, The Inn at Little Washington, where he offers a seasonal appetizer of smoked trout mousse topped with trout roe and served over house-made, ricotta-stuffed everything doughnuts. At Maryland’s Thacher & Rye, James Beard best chef semifinalist Bryan Voltaggio prefers a trout amandine served over marcona almond milk with smoked turkey–braised collard and kale greens, and creamy cheddar corn grits.

The Walkers’ completed their processing facility in 2023 and launched an online store that lets customers order fish, trout cakes, and seasonal dips.

A new outdoor dining area has brought quarterly farm dinners with star regional chefs. And a recently completed onsite Airbnb cabin lets visitors experience the farm firsthand.

“Sometimes I look out at the ponds and mountains and see my kids playing in the yard and it all feels so surreal, like, ‘How’d I get so lucky?’” says Ty, now a father of three. “I can’t tell you how fulfilling it is to wake up every day knowing my job is to help more people taste locally-raised trout than ever before.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook