What It’s Like to Live on the Sea Floor to Simulate Life in Space

Researchers squeeze into an underwater habitat off Florida to help prepare for missions to the Moon and beyond.

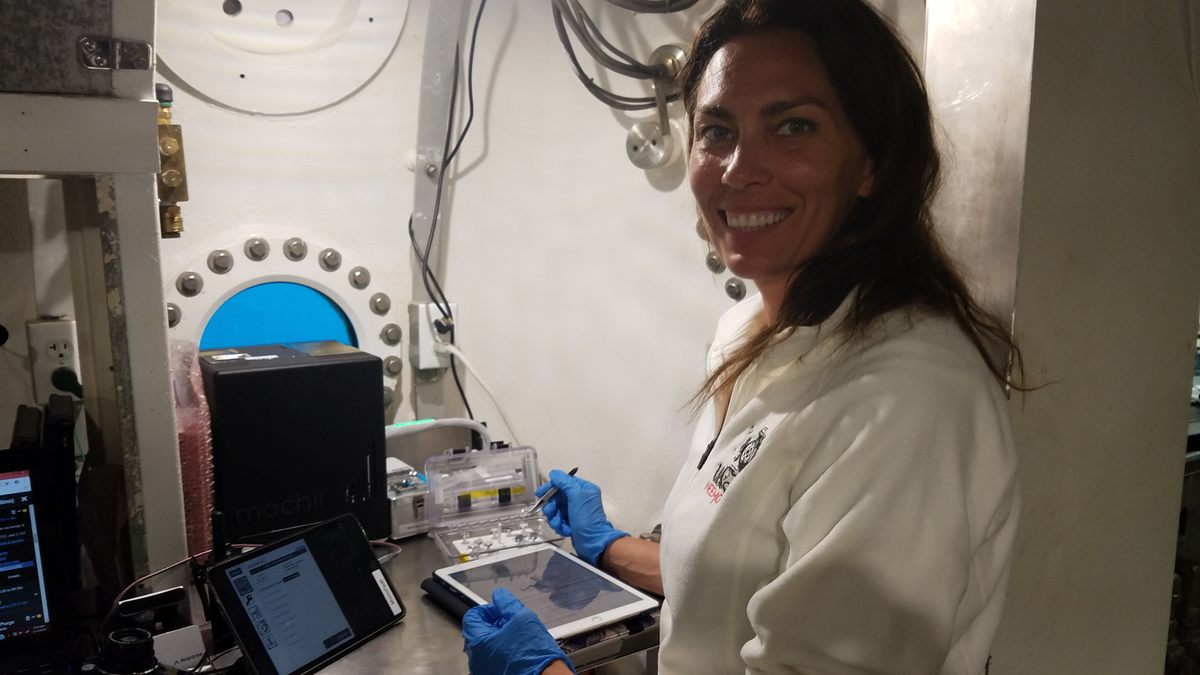

To Csilla Ari D’Agostino, the Aquarius Reef Base—submerged in green-blue water, encrusted with algae and barnacles—looked more like a shipwreck than a place to live. D’Agostino is a comparative neuroscientist at the University of South Florida, and an avid diver who has visited the underwater worlds in Hawaʻi, Indonesia, the Philippines, Ecuador, the Maldives, and more. In June 2019, she spent nine days living inside the Aquarius facility, 62 feet underwater, more than six miles off the coast of Key Largo, Florida.

D’Agostino packed into the 400-square-foot laboratory and living space with five other crew members of NASA’s Extreme Environment Mission Operations, which conducts expeditions to simulate the environments that astronauts might face in the course of space exploration. Down on the ocean floor, the crew mimicked rescues, tested out new equipment, and—for D’Agostino’s work—kept meticulous logs of what they thought and felt along the way.

Atlas Obscura caught up with D’Agostino once she had readjusted to life on the surface.

What can researchers learn about humans in space by studying them underwater? After all, the moon is very different from the ocean floor.

Basically, the idea is that we can simulate weightlessness because we are underwater. That’s the only possibility on Earth unless you do an airplane ride where there’s a few-second free-fall to mimic weightlessness. Other than that, the only option is underwater.

It’s important to understand how equipment responds when there’s no gravity, or there’s a different kind of gravity than we experience on land—and how our body can handle that kind of equipment. We might think, “Oh, we can just easily pick that up and put it here or there,” but it’s different.

When we went out of the habitat, we sometimes tested equipment that needs to function in different gravities. We had our regular dive gear and a heavy helmet on, which weighs 32 pounds. Still, we were kind of floating. On Mars and the lunar surface, there is a certain amount of gravity, so we put lead cubes on to weigh ourselves down to get as close as possible to the kind of gravity we would experience. We had a cart that we loaded with some of the equipment we needed to collect and analyze samples. If we didn’t have enough weight on, we couldn’t pull with enough power to actually move the cart.

Our crew tested a lunar evacuation system that the European Space Agency has been working on. If an astronaut is unconscious or injured, or not able to help themselves, another astronaut would need to transport that person to safety. Sometimes it’s hard to handle things in bulky dive gear or space suits, and hard to move even not-so-heavy objects, so they developed equipment to make this process easy—to pick up and transfer an unconscious astronaut from one point to another. The whole purpose was to test the equipment and give feedback to improve and optimize things.

How did you get down there, and then in and out of the habitat?

You swim down, like a regular scuba diver. There’s a “moon pool” [also known as a wet porch]. Imagine that you turn a cup upside down, and press it down in the water. The air is still inside the cup; you’re in an air bubble. We just swam underneath and went inside the habitat. The habitat is basically open—there’s an opening to the water all the time. But the air pressure in the habitat means the water can’t enter.

We could easily go in and out of the habitat to conduct experiments, but not up to the surface. After 24 hours at that pressure, our bodies became saturated with nitrogen. Without a decompression protocol, we could die. That’s the other thing that’s similar to space: You can’t just return to land.

I know that astronauts sometimes take things with them to space, from seeds to a ham sandwich. Did you pack anything special?

There’s not much room to store anything at all. Just basic clothing, whatever you need for diving, and maybe one or two smaller personal items. I took a family picture, and a Hungarian bookmark—I’m from Hungary—from my parents. Red, white, and green—the colors of the Hungarian flag—are embroidered on it.

There’s no room for extra stuff, and it can also be dangerous for various reasons. Things can be flammable down there that wouldn’t be flammable on land; because under the higher pressure, oxygen is more flammable. Somebody a couple missions ago was trying to use a hair dryer, and it got a little spark because there was a little piece of hair stuck in it. Chemicals that you would use for experiments or preservation on land could cause serious issues down there.

What did you do your last night on land? Any last hurrahs?

We knew we’d be eating basically freeze-dried camping food down there; it’s not like everyone’s taking their favorite meals. We knew that the next nine days were going to be a little restricted. Before we left, the crew, together with our spouses, went to a very nice restaurant by the sea and we ate everything we wanted. I had chocolate cake, and I was really full!

Basically, down there, you just put hot water in a packet, let it sit for 10 minutes, and then it’s a warm meal. Mainly, I ate chicken breast with mashed potatoes. That was my favorite. They also had beef, rice, and vegetables. It was pretty good, surprisingly. Well, after eating the same thing for nine days, it wasn’t that enjoyable. But it was relatively good.

How did you spend your days down there?

Our schedule was very tight, and was determined months before the whole mission. It was on software called Playbook that we checked all the time—you saw the current time and your scheduled tasks. We knew that when we woke up, we had 10 minutes to do this, 30 minutes to do this, two hours to do this.

In the mornings, we had to fill out a test about how stressed we were, and then check on our iPad to see what our tasks were. Sometimes there were things we needed to do before breakfast, such as test our blood before eating or drinking anything. Usually in the morning we had a meeting with surface mission control to go through what we needed to pay attention to during the day. We had a radio channel kind of thing, like a walkie-talkie, and they also had 24/7 video access to us. There was a meeting in the evening, too—what went wrong, why did it go wrong, how should it have been better, what’s the plan for tomorrow.

Everything was scheduled very specifically. Some experiments needed more space, or space that other people would use for other experiments, so we couldn’t overlap, because there’s such limited room inside. If an experiment needed two laptops, we had to work after each other—we couldn’t fit two laptops on the desk. Sometimes technical issues came up, things shifted, and we had to work hard to get back on the schedule.

Sometimes we would go outside and do more physically strenuous stuff for five hours [to simulate spacewalks]. We tried to shift so everybody had a day of rest inside and then a day outside and then a day inside. It didn’t always work like that, but that was the goal.

There was a way to get a bit of exercise inside, too. We had to test an exercise machine that they are planning to send to the International Space Station [ISS]. The goal was to give feedback—what’s good, what’s not so good, how should it be better? It was kind of like a rowing machine, but you do it standing, and the weight is attached to your waist, and you basically do squats. There were different playful things on the screen that give you directions about when and how to squat. We were laughing so much.

Was there anything about life in the habitat that was harder or easier than you expected?

The shower and bathroom area was really, really small. Six of us needed to use one bathroom. It was basically just a curtain in the corner. People were working around you when you were in the bathroom. They had stuff to do in the meantime!

I know you were interested in tracking cognitive performance—reaction time, memory, decision-making, and more—and also data about sleep quality and stress. How did you measure that?

We used questionnaires, which included questions about how you feel, whether you’re stressed about what’s coming up today, whether you feel rested. We had many, many questionnaires, and specific times we would answer them. When we wanted to look at how task load influenced our performance, we would ask questions when we came back from five hours of doing technical stuff on the coral reef. Then we would ask questions about how physically strenuous it was, and how much time pressure you felt, and how mentally difficult the task was. People either filled out the questionnaires on paper, if they were in the habitat, or on waterproof iPads if they were outside.

On the iPad, we used the same software that they use on the ISS to evaluate working memory, problem-solving ability, reaction time, and more. These are short, couple-minute tests. I was curious to see how the workload, pressure, stress, the time, all these variables would affect it. We did it before the whole mission, inside the habitat multiple times, outside when we went to the simulated spacewalk. We wanted to see how simply being in the water affected your reaction time, compared to how five hours working on a mentally or physically demanding exercise underwater was influencing these variables. I’m still analyzing lots of data, and then we need to publish it in scientific channels. It’s probably going to take a couple months or even a year.

How did you sleep? It’s hard for me to picture sleeping underwater for so many nights.

We didn’t really feel like we were underwater. At first, when we got inside the habitat, we felt a little bit of pressure in our ears, but we got used to it in like half an hour. After that, you don’t really feel like you are underwater. It’s just the basic white noise, all the hums, of the systems operating. I didn’t care—if I am sleepy, I will sleep.

I knew I had to wake up at 6:30, and we had a schedule until the end of the day, and then I added some more experiments I wanted to do that were not NASA-related. I also have a National Geographic Ocean Explorer project, and I wanted to run a small remotely operated vehicle from the habitat at night [to study sponge spawning]. I had to wait until it was completely dark. Those days were the ones with the longest daylight, so I had to wait until almost 10:00, and then had to start doing something. I didn’t go to bed until 11:00, maybe.

Every single day was scheduled, and I didn’t really have time to check my emails, and my students were helping coordinate some things on the surface. Sometimes at night I woke up thinking, “Oh my god, I didn’t check my email,” and responded to emails then. I didn’t sleep much, but I didn’t feel sleep-deprived then. After the whole mission, I felt that I needed much more sleep than normal. I think my body was just catching up.

How did nine days underwater stack up to other diving you’ve done?

What made it easier is that we prepared for a long time and very, very thoroughly for everything—for all kinds of circumstances. We knew that about 100 people were watching us continuously, and would help us if anything went wrong. If you think about it, it’s probably safer than much of the regular scuba diving people do around the world. We mentally and practically prepared so much, so I wasn’t that stressed. Sometimes, when I go on a regular scuba dive and we don’t expect difficult conditions and those do come up during the dive, that can be more stressful.

I’ve always loved reading astronauts’ accounts of looking down and seeing Earth far below them. You kind of had the opposite perspective. What did you see, and how did it affect the way you think about the planet?

We had windows, so we could see outside. We saw everything you see diving in a tropical ocean—turtles, rays, groupers. Because there were lights around the habitat, plankton and little organisms came to the window or near the habitat, and those attracted bigger fish, and then those attracted bigger fish, too. Of course, we couldn’t spend too much time on the animals.

We could also see the light, and approximately how the weather was—sunny or stormy, maybe, if the visibility got bad because waves had stirred up the sand. We had some kind of connection with the land, but we were very much aware that we were trapped, in a way—we couldn’t just return whenever we wanted to.

It was some kind of relief to be back to our normal environment. It made me appreciate the forces of nature, and the sea, and the life-forms that are able to adapt to it. It wasn’t even that harsh where we were—but imagine how many deeper, harsher places there are. It made me appreciate what’s able to cope in those circumstances. Obviously, we are not able to—we’re dependent on technology.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook