Searching for Genesis StoryTime, a Lost Canadian Cable Channel

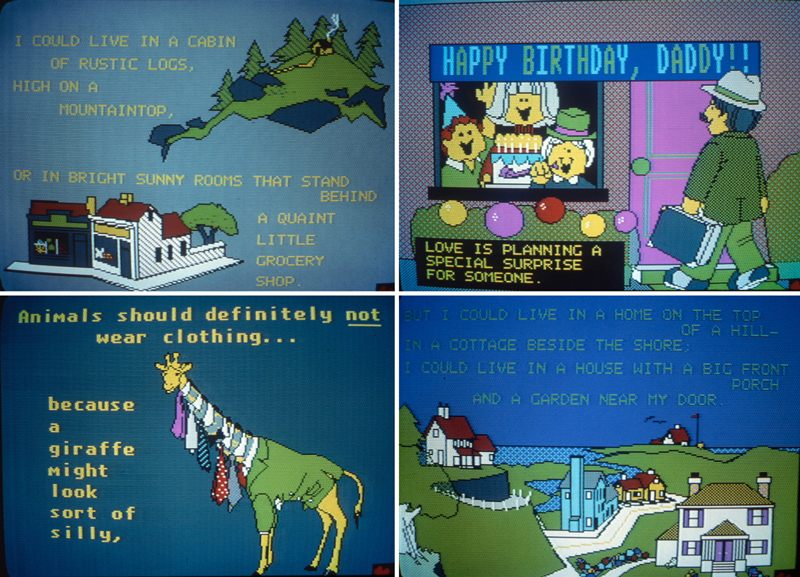

It used a technology known as videotex to distribute children’s books over television screens.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

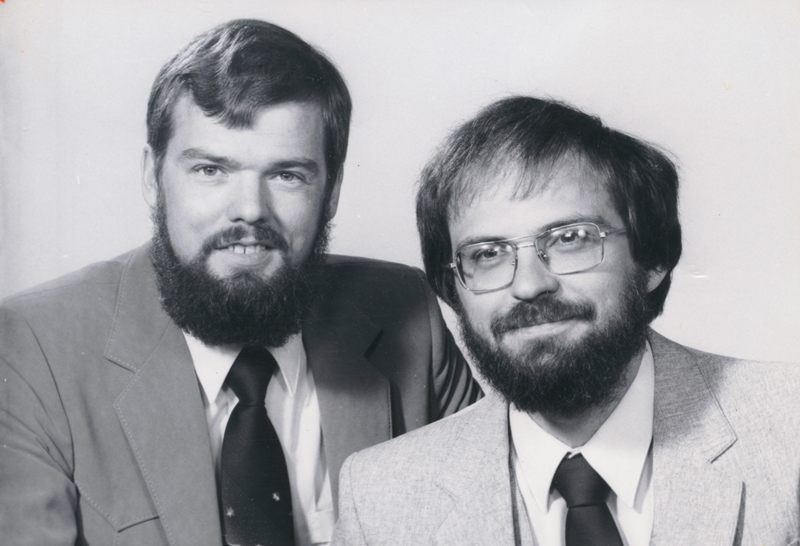

The late 1970s and early 1980s were an exciting time for technology and communications. Engineers and programmers were racing to put new developments to use, some seeking to make the world a better place, others just wanting to see how the technology would develop. Greg Stetski and Art Doerksen wanted to do a bit of both.

Genesis StoryTime debuted in 1982 to a small contingent of cable service subscribers in western Canada. The brainchild of Stetski and Doerksen, two Canadian engineers, Genesis StoryTime used a service known as Telidon to distribute children’s books over television screens. Describing the technology powering the channel can be challenging—it’s somewhat similar in nature to the technology used on the Prodigy computer network, an infamously hard-to-archive service—but comparing it to flight information monitors at airports, in which a computer is used to display simple information over a variety of screens, is useful.

Developed by Canada’s Communication Research Centre, Telidon is videotex technology that uses coordinated shapes to create simple graphics and even crude animation. Some hail Telidon as a pioneer of the graphical web. Unfortunately, because of the constraints of this technology, graphics were about all Genesis StoryTime had to offer. Sound wasn’t available. While some saw this as a limitation, Stetski and Doerksen saw an advantage.

“The channel was always intended to be silent,” Stetski says from his home in Manitoba, Canada. “We wanted to use television to bring parents and kids together.”

Publishers were quick to jump into the project, and soon the channel had more than 300 stories. With a 90 words-per-minute read rate, stories typically ran from 10 to 15 minutes. While the majority of the content came from mainstream authors, like Roger Hargreaves of Mr. Men fame, Stetski estimates about 10 percent were Bible stories. The decision to run the Bible stories was somewhat practical as the rights were in the public domain. However, Stetski kept them in rotation out of personal conviction, despite financial pressure to do otherwise.

“[One cable system owner] said if I got rid of the Bible stories he’d put us in every home in Florida,” Stetski says. Still, he kept the faith.

The channel steadily grew to reach 40 cable stations across North and Central America, and Stetski says they hit between two and three million at one point. Nevertheless, footage of Genesis StoryTime is incredibly difficult to come by. It was never intended to be recorded then played. What aired was a computer program generating a series of coordinated graphics and text. As a result, there are almost no long-lost VHS copies. Nothing to upload to YouTube.

One writer referred to footage of Genesis StoryTime as a “pop culture ghost.” Even the Barco Library at the Cable Center, an archive dedicated to the preservation of audiovisual resources and equipment exclusive to the cable and media industry, only has still images of Genesis StoryTime.

As near as we can figure, this, from Stetski’s personal collection, is the only known footage of content from Genesis StoryTime on the internet.

Locating even a brief glimpse of Genesis StoryTime was no small effort. We reached out to niche YouTube channels and specialty archives. We even called the Christian Broadcasting Network because there was a tip they had aired some of the Bible stories, but weren’t attached to the Genesis cable system—in other words, they had tapes. None of it panned out it, until Stetski himself shared the clip above with us. But as we waited and looked, we learned more and more about the channel and the men that sweated through to make it a reality. Then we learned what happened after it failed.

By 1990, the Genesis Research Corporation, the company behind Genesis StoryTime, was collapsing when the owner of a Winnipeg commercial real estate firm swooped in to save the day.

“We had come to a place where we needed someone else to come take it over,” Stetski said to the Winnipeg Free Press in 1990. “We were on the verge of shutting it down and that’s when Helmut came on the scene.”

Helmut Sass purchased Genesis Research Corporation after seeing StoryTime while on vacation in the U.S. His intentions for the company weren’t profit-oriented. “My motive isn’t so much to make money in this, but to provide wholesome stories for children again,” Sass told the newspaper.

The timing of the transition also provided an opportunity for Art Doerksen to change his life. “He gave me all his parkas and winter boots and moved to Vancouver!” Stetski says. Doerksen ultimately ended up pursuing a career in alternative medicine, becoming involved in the design and marketing of zappers, devices that purportedly kill “parasites, bacteria, viruses, molds, and fungi.” Though the two remained friends until Doerksen’s death in 2016, Doerksen wasn’t involved in the next iteration of Genesis StoryTime, known as Story Vision Network, and rarely returned to Winnipeg. Nevertheless, Stetski attributes much of their success to Doerksen, and called him “one of the best engineers in Canada.”

Story Vision Network wouldn’t fare much better than Genesis, with the channel ceasing operations in the late 1990s. Stetski had moved on. He became a preacher and executive director of the Union Gospel Mission Winnipeg, a post he only recently retired from.

He would also go on to continue the work of Genesis StoryTime, albeit in a different form. Since he still retained the rights to the images that accompanied the Bible stories, he began distributing them as PDFs to churches and youth groups around the world. His organization, Bible for Children, now offers 60 Bible stories in dozens of languages. The nonprofit is even on the App Store and Google Play.

The men behind Genesis StoryTime leave a hazy legacy. Their work was innovative and somewhat popular. Stetski says that Genesis StoryTime was receiving 200 to 300 letters a month from children requesting stories or generally just saying they liked the channel. However, evidence of their endeavor is scant, relegated to newspaper clips and the occasional blog bemoaning the lack of footage. These days, Greg Stetski is better known as a pastor, Art Doerksen is better known for his advocacy of alternative medicine, and Genesis StoryTime remains largely a footnote in television history.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook