Why Doesn’t Tennis Have a Single Professional League?

Qatar Open, Doha. (Photo: Kate/flickr)

Qatar Open, Doha. (Photo: Kate/flickr)

These days, most casual tennis fans know the sport by knowing its superstar international players: Serena Williams, Roger Federer, Novak Djokovic, and Maria Sharapova, among others, are household names, even in countries like the U.S. where tennis is, give or take, only the 6th-most-popular sport.

But there is a strangeness at the heart of the sport that separates it from most other popular athletics in America: there is no one league. Like the New York City subway system, actually a smashed-up combination of several earlier networks, loosely linked together in a desperate effort to make the sport make sense. (It doesn’t entirely succeed.)

For fans, this means that, at any given moment, some of the world’s best players might be competing in a little-known tournament near you.

Wimbledon Championships, 1883. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Wimbledon Championships, 1883. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Competitive tennis took off in the late 19th century, the time period when Wimbledon, the U.S. Open, and the French Open, three of the biggest four tournaments currently in the world, were established. The Australian Open dates back to 1905. In 1913, the national tennis associations of 15 nations came together to create one worldwide governing body, at first called the International Lawn Tennis Federation (ILTF). (The “lawn” part was later removed.) The ILTF formalized the rules of the sport, declared an official language (French, with an English translation), located the headquarters (Paris), created a team championships (later to be called the Davis Cup, sort of a World Cup of tennis in which players represent their country). Written into the rules was a little gift for England: the world championships on a grass court would be held, forever, in Great Britain.

But the ILTF, like FIFA for soccer, was simply an umbrella organization: leagues sprouted up all around the world, and individual tournaments, and the entire thing turned into chaos.

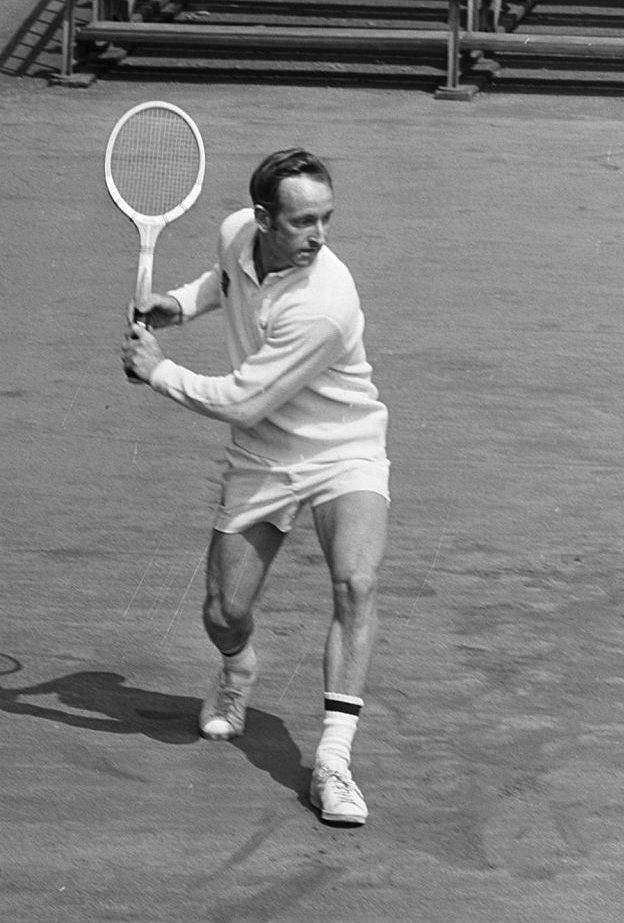

Rodney Laver at the 1969 Top Tennis Tournament in Amsterdam. (Photo: Evers, Joost/Anefo/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0nl)

Rodney Laver at the 1969 Top Tennis Tournament in Amsterdam. (Photo: Evers, Joost/Anefo/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0nl)

The tournaments now known as the Grand Slams were all independent tournaments, and all were only open to amateurs, which sounds bizarre by today’s standards. Tennis was, until 1968, structured sort of like figure skating: The tournaments were for “amateurs,” and once you turned pro, you performed in exhibition matches organized by a league, and could compete in less popular tournaments like the Wembley Championship and the Tournament of Champions. Amateurs who competed at Wimbledon or the U.S. Open were compensated for travel expenses and nothing else. No prize money. Like in college sports, the promoters and stadiums and league officials raked in money on the much-more-popular amateur tournaments, while the players either went penniless or (more often) broke the rules and accepted money to appear. Eventually, they’d turn pro and be forgotten.

Everything changed in 1968, because the Grand Slams opened their doors to professional players. The period after 1968, up to the present, is referred to as the “Open Era.” All of a sudden, there was money to be made in tennis, not just by the promoters and officials but by the players as well. Professional players signed contracts with a few competing leagues, which dictated which tournaments the players would participate in. By 1970, there were two dominant leagues: National League Tennis (NTL) and World Championship Tennis (WCT).

This, too, was chaos, because if one particular league didn’t like one particular tournament, every player would simply not play. In 1968, the WCT’s eight best players didn’t compete in the French Open. In 1970, NTL players boycotted the Australian Open. It would be as if the NBA boycotted the Olympics one year. Who would watch Olympic basketball with nobody from the NBA?

Competition was insane. Leagues banned their players from playing in the world’s most popular events. Third-party leagues sprung up and only added to the confusion. WCT absorbed NTL, which made things simpler but also increased WCT’s bargaining power, which was very bad. Eventually the ILTF, in 1972, flipped out and simply banned all professional contract players from playing in any of the big events, including the 1972 French Open and Wimbledon.

The Chennai Open . (Photo: Ashok Prabhakaran/flickr)

The Chennai Open . (Photo: Ashok Prabhakaran/flickr)

To fix these ridiculous problems, the players took matters into their own hands. In 1972, male players founded the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP), basically a union to protect their interests. In 1973, female players, having been left out, formed the Women’s Tennis Association (WTA). This led to the ILTF saying screw it, and combining with the WCT, which lasted for a whopping four years before the WCT separated again. Throughout the 1980s, the WCT operated a smaller tour while the ILTF (by this point simply the ITF) operated the Grand Slams.

Eventually, in 1990, the ATP took over the WCT’s tour, and named it the ATP World Tour, which began with nine tournaments across the world. More importantly, the ATP began doing their own rankings, which the ILTF/ITF was forced to begin using as well.

What this means is that for the world’s top players today, there are near-constant tournaments to play in. Of course you literally can’t (and wouldn’t want to; tennis is a physically demanding sport) play in every tournament, so you pick and choose which ones to compete in. “Nobody plays every single one; sometimes there are two or three a week,” says Joel Drucker, who covers tennis for the Tennis Channel (and pretty much everywhere else). Partly that decision will be made by how healthy the player is, but also largely by points, which make up a player’s overall world ranking.

Djokovic in Dubai. (Photo: Marianne Bevis/flickr)

Djokovic in Dubai. (Photo: Marianne Bevis/flickr)

Each tournament is worth a specific amount of points, and the tournaments are classified into a few tiers based on how many points and how much prize money they offer. The smallest tournaments are classified as the IFT Men’s Circuit Tournaments, which offer, for the winner, only 35 points, and around $10,000 to $15,000 in prize money. (In all the tournaments, those who don’t win still get some points and some money depending on how well they performed.) There are hundreds of these tournaments, all around the country.

The next step up is the ATP Challenger Tour, which gives up to 125 points and around $220,000 in prize money for the victor. Then the ATP World Tour 250 series, the ATP World Tour 500 series, the ATP World Tour Masters 1000 series, and finally, the Grand Slams. (Those numbers refer to the maximum number of points you can get. The Slams are worth 2,000 points for the victor.)

What this means is that, at pretty much any given moment, there is a tournament going on somewhere near you. Most of these aren’t even televised; nobody much cares about a Challenger tournament in Marrakesh or Knoxville or Tianjin. But the 250, 500, and 1000 series routinely host the world’s best players (sometimes they have to pay the players to come, but still) in much smaller and more intimate arenas. If you want to see Roger Federer play Novak Djokovic, the best place to do it isn’t the U.S. Open or even Wimbledon. It might be, like…Cincinnati. Or Rotterdam.

Queen’s Club London Double semi-final in 2012, with Novak Djokovic and Jonathan Erlich v Julien Benneteau and Michael Llodra. (Photo: Kate/flickr)

Queen’s Club London Double semi-final in 2012, with Novak Djokovic and Jonathan Erlich v Julien Benneteau and Michael Llodra. (Photo: Kate/flickr)

I spoke to a few tennis experts about their favorite tournaments. “Indian Wells [in California’s Coachella Valley] has a great atmosphere, kind of like a spring training. They have all the best players, their venue is significantly more intimate than the Slams, it’s [held in] March, so the players are still quite kind of chilled out, and you can see them up closer,” says Drucker. The players love Indian Wells (except, maybe, for Serena and Venus Williams, who boycotted the event for over a decade) as well as the Queen’s Club Championships in London and the Dubai Tennis Championships, which until recently were delightfully known as the Dubai Duty Free Tennis Championships.

Fans tend to love the Halle Championships in north-central Germany, a high-tech grass-court tournament that serves as a warmup for Wimbledon. Or you could go for Monte Carlo, overlooking the Mediterranean. Or the neon purple-and-green courts at the Qatar Open, in the desert of Doha. The one that everyone seems to agree is the worst? The China Open, in Beijing, which fans describe as having horrible weather, egregious air pollution, and no love from fans.

The tournaments tend to air on the Tennis Channel, and old matches routinely show up in their entirety on YouTube. But the best thing about these smaller tournaments is exactly that: they’re smaller. Courtside seats at the U.S. Open finals will run you over $8,000, minimum. In Cincinnati, to see the same players? Less than $600.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook