The Ornate Ice Cream Saloons That Served Unchaperoned Women

They welcomed women back when American restaurants prohibited dining without a man present.

On August 28, 1900, Rebecca Israel decided to treat herself to dinner at Cafe Boulevard, a fashionable restaurant in the heart of Manhattan’s Jewish theater district. Despite being polite and well-dressed, Rebecca was refused a table and asked to leave. The restaurant’s owner, Igantz Rosenfeld, had a strict policy against serving women who were unaccompanied by men. Rebecca sued him for discrimination, but the case was dismissed by the New York Supreme Court in 1903.

Throughout the 19th century, restaurants catered to a predominately male clientele. Much like taverns and gentlemen’s clubs, they were places where men went to socialize, discuss business, and otherwise escape the responsibilities of work and home. It was considered inappropriate for women to dine alone, and those who did were assumed to be prostitutes. Given this association, unescorted women were banned from most high-end restaurants and generally did not patronize taverns, chophouses, and other masculine haunts.

As American cities continued to expand, it became increasingly inconvenient for women to return home for midday meals. The growing demand for ladies’ lunch spots inspired the creation of an entirely new restaurant: the ice-cream saloon. At a time when respectable women were excluded from much of public life, these decadent eateries allowed women to dine alone without putting their bodies or reputations at risk.

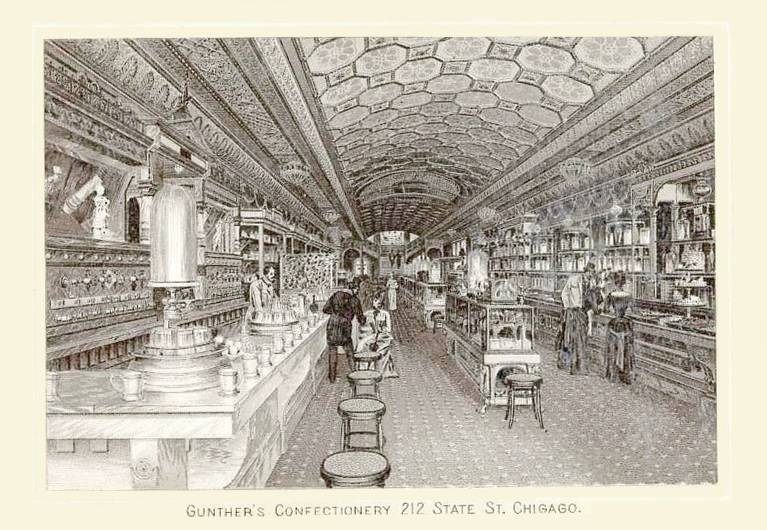

The first ice cream saloons were humble cafes that served little more than ice cream, pastries, and oysters. As women became more comfortable eating out, they expanded into opulent, full-service restaurants with sophisticated menus that rivaled those at most other elite establishments. In 1850, a journalist described one ice cream saloon as offering “an extensive bill of fare … ice cream — oysters, stewed, fried and broiled; —broiled chickens, omelettes, sandwiches; boiled and poached eggs; broiled ham; beef-steak, coffee, chocolate, toast and butter.” According to the historian Paul Freeman, the 1862 menu of an ice cream saloon in New York ran a whopping 57 pages and featured mother of pearl detailing.

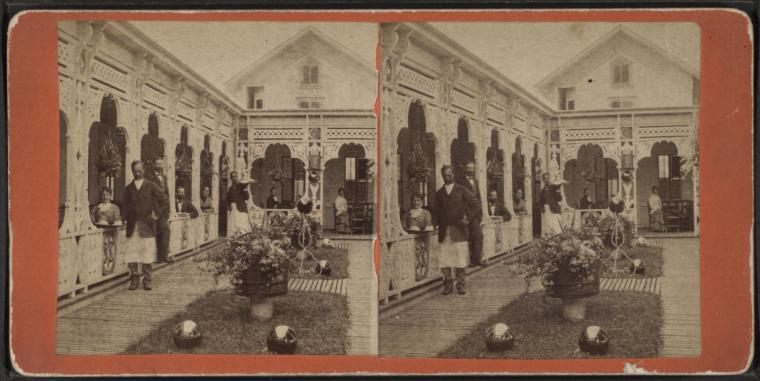

Ice cream saloons proliferated in urban shopping districts in the 1850s and were immensely popular with the growing number of wealthy women who spent their afternoons shopping and promenading along the avenues. After a long day at the department store, the carriage trade headed to the ice cream saloon, to, in the words of one commentator, “exchange a dish of scandal or gossip, as well as sweetmeats.” Towards the end of the century, department stores started to open their own restaurants. But as the New York Times noted in 1866, for a long time ice cream saloons were “almost the only place where ladies could go unattended by gentlemen and satisfy their appetites, rendered sharp by their shopping excursions.”

Beginning in 1839 with the Tremont Hotel in Boston, large hotels regularly set aside space for a ladies’ ordinary, a separate dining room for women and children. Men were only admitted if they were dining with women, generally their wives or other female relatives. But few establishments had the space or resources to provide unescorted women with such posh accommodations, and those that did were only accessible to the elite.

Unlike ladies ordinaries, ice cream saloons didn’t formally restrict male patronage. Instead, they established themselves as respectable restaurants simply by catering to women’s culinary and decor preferences. Though many ice cream saloons offered hearty meals, they tended to emphasize oysters, ice cream, and other light bites. “Special pains are taken in many places to cater to these fair lunchers,” wrote the New York Times in 1890. “While women are not all light eaters, most of them are partial to dainty tid-bits, pastry and ice cream.”

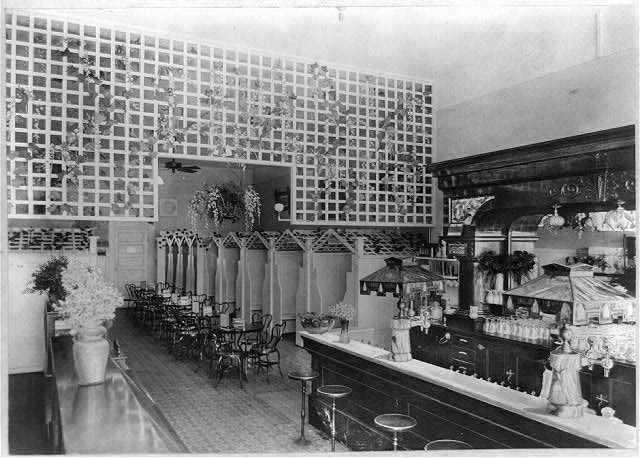

In an effort to create a female-friendly atmosphere, many restaurants were outfitted with domestic decor. Heavy draperies, plush armchairs, and marble fireplaces were used to create a parlor-like atmosphere. Newspaper advertisements often used domestic language to signal that ice cream saloons were respectable places for women to dine alone. In 1888, an advertisement for a ladies’ lunch room in San Francisco claimed to be “the only quiet, home-like down-town Restaurant for Ladies and Gentlemen.”

According to food historian Cindy Lobel, this is why some women’s restaurants began to be referred to as parlors, or more specifically ice cream parlors. As a result, many Americans still go to “ice cream parlors” today.

In New York, the most famous ice cream saloon was Taylor’s Saloon, which was crowned “the largest and most elegant restaurant in the world” by Putnam’s Monthly in 1853. The 7,500-square-foot dining room was lavishly decorated with marble floors, mirrored walls, ceiling frescos, and a 17-foot tall crystal fountain. Bowl upon bowl of fruit and candy were displayed on large marble countertops, along with intricate sugar sculptures and freshly cut flowers. The magnificent scene was described by Isabella Bird, an Englishwoman visiting the United States, as “a perfect blaze of decoration … a complete maze of fresco, mirrors, carving, gilding, and marble.”

Although ice cream parlors had an air of dainty domesticity, they also developed more sultry reputations. At the time, they were one of the few places where both men and women could go unchaperoned. As a result, they became popular destinations for dates and other illicit rendezvous. “Did a young lady wish to enjoy the society of the lover whom ‘Papa’ had forbidden the house?” the New York Times wrote in 1866. “A meeting at Taylor’s was arranged, where soft words and loving looks served to atone for parental harshness, and aided the digestion of pickled oysters.”

Innocent young couples weren’t the only pairs tucked together in the velvet booths. During a trip to Taylor’s, one writer observed “a middle-aged man and woman in deep and earnest conversation. They are evidently man and wife—though not each others!” Moralists were also outraged by the presence of pimps, prostitutes, and women “who were not over particular with the company they kept.” These scandalous scenes prompted rumors of ice cream “drugged with passion-exciting Vanilla” that seduced virtuous women into taking “the first step…which leads to infamy.”

These charges did little to dissuade respectable women from patronizing ice cream saloons. In fact, their reputation as “a trysting ground for all sorts of lovers” may have made the saloons all the more enticing. According to the Times, Taylor’s “always maintained its popularity, in spite of (or perhaps because of) rumors that it afforded most elegant opportunities for meetings not entirely correct.”

In time, restaurateurs came to recognize that serving women was a lucrative business. By the end of the 19th century, women had a variety of restaurant options to choose from, including more reasonably priced lunch rooms and cafeterias. To compete, the gilded ice cream saloons gradually evolved into more modest establishments, which made them available to working-class women. But while eateries such as Taylor’s served mainly the wealthy, ice cream—and the palatial establishments where it was served—played an important role in ensuring that American women could enter a restaurant with or without a man.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook