The Greatest Witch Movie Ever Made

Why do modern witches embrace “The Wicker Man”?

I came to Salem on a witch hunt.

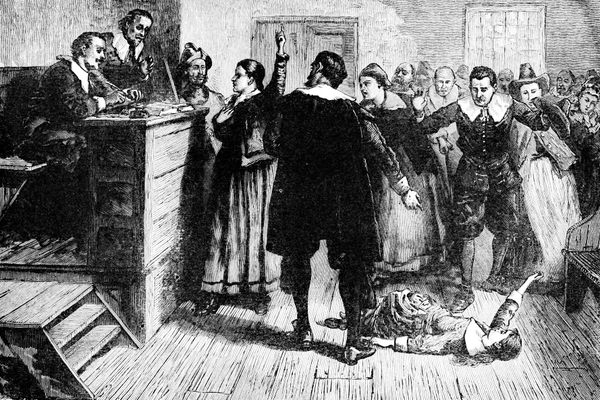

Obviously not the kind of witch hunt that made Salem infamous. That 1692 episode of mass hysteria sentenced 20 innocent Puritans to death, almost entirely women, in an American chapter so wrong it literally birthed the phrase “witch hunt.” My visit would be less dramatic. I was behind the wheel of a borrowed Toyota Scion, searching for the Salem Witchcraft Festival—four days of workshops and panels from witches, folklorists, and other pagan practitioners. For those who believe in, study, or are simply curious about witchcraft, it’s an opportunity to meet and learn from their community. The vibe is an intriguing mix of esoteric spiritualism and tightly scheduled lectures, like a software convention if Dell representatives wore a lot more black.

I came to the festival for a special screening of The Wicker Man. The gathering’s cofounders, Jacqui Allouise and Matthew Venus, included the 1973 horror film as a marquee event of the weekend. The cult classic was followed by a discussion between occult figures like writer and former MTV News anchor Meredith Graves, who established “Witchstarter” in 2022, and consultant-practitioner Sasha Ravitch. What made this panel unique was that it discussed The Wicker Man from the perspective of witches, rather than someone actually scary, like a film critic.

The Wicker Man recently turned 50, and the man looks damn good for his age, let alone for someone whose face is made of twigs. In 2020, the Independent placed it “among the most influential horror films of the last 50 years.” It’s been called “the Citizen Kane of horror movies.” Even Christopher Lee himself said The Wicker Man was “the finest film I’ve ever been in,” and that dude played freakin’ Saruman in Lord of the Rings.

As my trip to Salem all but confirmed in my mind, however, it goes beyond those accolades: The Wicker Man may be the greatest witchcraft film ever made.

More precisely, The Wicker Man is probably the most beloved movie among witches. It was chosen above any other film to show before a panel of witches, in a theater of witches, in a place with the nickname “Witch City.” And while that name is so insensitive I could feel Elizabeth Proctor rolling her eyes at me from beyond the grave as I typed it, this accolade highlights The Wicker Man as uniquely important among covens. It’s this passion for the movie so many witches hold that I find remarkable.

The film, directed by Robin Hardy, follows Sergeant Howie (Edward Woodward), a police officer who flies to the remote (and fictional) Scottish island of Summerisle to investigate a little girl’s disappearance. Howie is welcomed warmly by the townspeople, including the innkeeper’s daughter, Willow (Britt Ekland), and their leader, Lord Summerisle (Lee). But the dogmatic Christian officer is appalled by the community’s belief in what he views as heathen gods, and he begins to suspect they plan to kill the missing girl in an occult ritual.

This description, however, doesn’t do justice to how unique, enigmatic, and straight-up strange The Wicker Man is. And these mysterious qualities, while rather witchy themselves, don’t reveal why The Wicker Man is so special. After all, there are dozens of witchcraft films more recent (The Witch), more successful (Harry Potter), or more explicitly about witches (The Craft) that could have been celebrated in Salem. Why The Wicker Man?

Modern witchcraft is hard to define—an issue it shares with many religions. Witchcraft itself is diverse in its beliefs, cultures, and rituals. Some witches don’t consider it a religion at all, but simply a lifestyle rooted in reverence for nature. Some witches consider Wicca distinct from witchcraft, others do not. Some witches reject distinctions altogether. But, generally speaking, witches and other sources I consulted consider it a spiritual practice—often with pagan roots and incorporating ritual—that includes folk magic, Wicca, esotericism, herbalism, and other beliefs sometimes called New Age. Modern witchcraft is often traced back to the mid-20th century, when a renewed interest in environmentalism, the founding of Wicca, the seeds of second-wave feminism, and a postwar world searching for spiritual guidance led people to beliefs outside mainstream or patriarchal “major” religions like Christianity.

Of course, I’m in no position to make broad claims on behalf of a spiritual practice I don’t belong to. I don’t call myself pagan (though an angry Catechism teacher once called me a heathen). So I reached out to some knowledgeable witches, including Amanda Yates Garcia, author of Initiated: Memoir of a Witch and host of the Between Worlds podcast, to hear their thoughts. We met in the lobby of Salem’s historic Hawthorne Hotel, a few blocks from where Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote The Scarlet Letter, which as a writer made me feel incredibly inadequate.

Garcia was raised by practicing witches who hosted moon circles right in their California home while enjoying some wine, and she says the film resonates with her for its accurately unembellished portrayal of contemporary paganism. “What witchcraft looks like in a hereditary witch’s family is not what it looks like in cinema,” she said. “It’s casual. It’s in your living room. It doesn’t have the romance of the Scottish Highlands. You know, huge icons and glamorous women and castles. So I think there’s that appeal.”

In fact, The Wicker Man’s scenery is almost dull. The film is part of a trio of influential witchcraft films—including Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) and Witchfinder General (1968)—known as “The Unholy Trinity.” But, unlike the other two parts of the trinity, The Wicker Man is set in contemporary times, and features no clear supernatural elements. It gives Summerisle’s villagers an eerily quotidian feel, enhanced by the brilliant work of costume designer Sue Yelland and casting director Maggie Cartier. When Sergeant Howie spots three figures glaring at him from behind ritualistic animal masks, the figures are also wearing typical 1970s hand-me-downs. Take out the occasional human sacrifice, and you could be watching a Michael Apted documentary. “Perhaps it all seems so real because the ‘old ways’ sit like vivid fissures in the surface of modernity,” said Sight & Sound, the British Film Institute’s monthly magazine. “The present is piled on top of the past, evoking a distinctly plausible world of folk tradition.” Far from being a comfort, this familiarity feels off-putting, in the uncanny valley, suggesting a mysterious world just below the ordinary.

Or, as Willow the innkeeper’s daughter might put it, “Some things in their natural state have the most vivid colors.”

The witchcraft that does find its way into The Wicker Man is also unspectacular. As a lay person, I didn’t even process some of it as witchcraft at all. “You’ll actually see people do witchcraft all through the film,” said Rebecca Beyer, a witch and botanist from North Carolina and author of Wild Witchcraft. “But it’s the way that people do magic in folk ways, accurately, and so it’s very subtle like that.” Nobody is turned into a frog in The Wicker Man. Instead, the frog is placed into a child’s mouth. Beyer, who practices Appalachian folk magic, was familiar with this tradition. “She is doing an English folk remedy, because the frog croaks. So when you put a frog in someone’s mouth with a sore throat, it takes away the sore throat. It absorbs it. It’s called ‘sympathetic magic.’” These specific rituals aren’t necessarily practiced by today’s witches, and some folklorists have pointed out inaccuracies in the movie, but the film still rings more true to witches than the stereotypical “cackling hag” that persists even today.

Not to say witches haven’t achieved incredible leaps forward since 1692, despite continued stigma (and worse). According to a survey of religions in the U.S. by Trinity College, the number of Wiccans grew from 8,000 in 1990 to more than 300,000 in 2008. During the same period “paganism” became Canada’s fastest-growing religion. And in 2017, the Department of Defense added “Wicca” to its list of recognized faith groups for members of the United States military.

What does The Wicker Man movie actually have to say about witches, though? Couldn’t one look at the villager’s duplicity toward Howie and the violent final act as a bleak depiction of witchcraft? Jason Mankey, author of The Horned God of the Witches, understands why pagans would still embrace the film. “The Wicker Man was the first movie to portray pagans in something close to a sympathetic light,” he told The Independent in 2020. “Sure, they have to sacrifice a person on May Day every once in a while. But for the most part their society feels like a rather joyous one.” And Vivianne Crowley, a Wiccan high priestess and former lecturer at King’s College London, told Religion News Service she was “astonished” by the movie when she saw it in 1974. “Suddenly paganism was out there and given a serious role in this movie even if some of the presentations weren’t particularly positive,” she said.

After decades of being portrayed as one-dimensional demons or angels, as the Wicked Witch or Glinda the Good, here was a film that portrayed witches as something more complex. As people capable of both great joy and kindness, and great acts of brutality. In other words, as humans.

All of this, of course, still doesn’t fully explain the unique allure of The Wicker Man. Maybe nothing can. Any film that pauses the action for a nearly four-minute maypole dance sequence is tricky to categorize. Its appeal is largely ephemeral, as if it casts a spell of its own over its audience. This is, after all, a movie so confounding the only way the 2006 remake could hope to top its oddity was to cast Nicolas Cage.

Shortly before I left Salem, while speaking with Garcia, I realized we hadn’t talked about the film’s biggest star (literally and figuratively), the actual wicker man. Unlike the movie’s other depictions of witchcraft, there’s no archaeological evidence pagans used them, and no reliable accounts of the ritual ever happening. Why, I asked, did the same filmmakers who spread so many familiar details throughout Summerisle conclude The Wicker Man with such a spectacular act of witchcraft fiction?

“I don’t think the filmmakers were interested in accuracy. I don’t think that that was their primary reason for making their film,” Garcia said. “I think that they were just putting in things that they thought had cinematic or visual interest.” Given what we had been discussing, this answer surprised me. But, she added, the visuals themselves brought the audience to a place that feels akin to the world of witchcraft: “That kind of magical realm of enchantment.”

Accurate or not, that final image, darkness falling on Summerisle as Howie howls through an agonizing end, threatens to break that enchantment. It’s a chilling conclusion, even if it is set to the jovial tune of the “Cuckoo Song.” (In fact, that song is half the reason the movie gives me nightmares.) It inevitably makes us think about our own deeply held beliefs. Even if wicker men were dreamed up by Caesar, sacrifices—animal and human—were a part of ancient religions. (Google “bog body” if you’re as morbid as I am.) Modern witchcraft, obviously, is not specifically drawing from those traditions. But it’s a tension between the past and the present that resonates with just about anyone (witch or not) who watches The Wicker Man—which, frankly should be everyone.

Beyer, who was, like me, in that enthusiastic crowd of modern witches celebrating the movie in Salem, doesn’t dismiss this tension. In fact, she suggests the unanswered questions are an essential part of what makes The Wicker Man great. “I think the movie is supposed to kind of leave the viewer asking, like, what parts of the past do we preserve? What parts of folkways are important to hold on to?”

It’s a question we may never have a perfect answer for, except that we should hold on to The Wicker Man as long as we can.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook