The Startling History of the Jump Scare

From 1942’s Cat People to cerebral jolts in Hereditary and Get Out, this cinematic scare tactic still shocks.

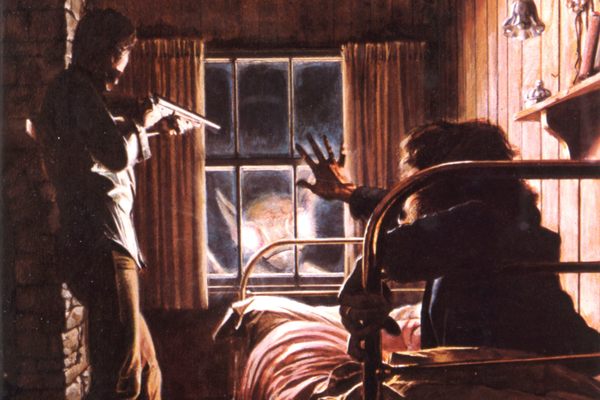

One of the most iconic moments in Brian De Palma’s 1976 movie Carrie comes right before the credits roll. By now the titular Carrie is dead, having massacred her high school bullies, stabbed her abusive mother, and destroyed her family home with herself inside. After the dust settles, we cut to a dream sequence with the sole survivor of this killing spree, a teenager named Sue.

For more than a minute, the camera lingers on Sue approaching the site of Carrie’s death and then laying down a bunch of flowers—a mournful moment abruptly interrupted by Carrie’s bloody hand bursting from the ground and grabbing her arm. The movie ends with Sue waking from this nightmare, screaming in her bed.

Carrie’s final-act stinger was a turning point for jump scares, interrupting what appeared to be a peaceful epilogue. It united viewers in a shared moment of tension-puncturing shock and, over the next decade, directors such as Tobe Hooper, Sam Raimi, and George Romero scrambled to deliver bigger and badder scares. Nowadays it’s hard to imagine horror cinema without this kind of short, sharp shock. Yet in the early years of film, different flavors of fear were in vogue, drawing from the 19th-century heyday of gothic literature and live horror theater.

Catering to a ravenous appetite for ghost stories, Victorian theater-makers used illusions like Pepper’s Ghost (which projected a translucent figure using a sheet of glass) and the Corsican Trap (which made an actor appear to rise from the ground). In Paris, the Grand Guignol Theatre became famous for embracing visceral morbidity, specializing in gory dramatizations of real-life murder and mutilation.

“As opposed to a slice of life theater, they developed a slice of death theater,” says Richard J. Hand, a professor of media practice at the University of East Anglia. He says that to satisfy the audience’s craving for gruesome thrills, Grand Guignol performances involved copious fake blood and depicted people being decapitated, skinned alive, and splattered with acid. Foreshadowing the notoriety of slasher cinema, the Grand Guignol promoted anecdotes of fainting audience members requiring treatment from the theater’s in-house physician. But while the gratuitous gore and marketing hype might prefigure modern slasher flicks, these early forms of shock entertainment are not precursors to the cinematic jump scare.

According to Hand, an expert on past and present horror theater, the element of surprise works differently on the stage than it does on a screen. Movie scares need to be fast and sudden, but in a live show, slowness is more effective. “You have that captive audience in that shared space, in that shared time,” says Hand. If something happens too quickly, the audience might miss it. Instead, theater relies on gradually building tension between the viewer and performer.

As scary fare transitioned from stage to screen, it took several decades for filmmakers to develop the correct formula of pacing and sound design to make audiences leap out of their seats.

The first cinematic jump scare is generally agreed to be in 1942’s Cat People. To modern eyes it’s pretty tame, featuring the abrupt arrival of a bus on a deserted street. Scare techniques only really began to escalate after American film censorship laws relaxed in the 1970s, ushering in an era of ax murderers, demonic possessions, and malevolent clowns. Eighties slashers perfected a reliable delivery system for adrenaline-inducing shocks and, while they’re not exactly considered high art, this kind of scare-centric filmmaking continually makes bank at the box office.

To state the obvious for a moment, horror thrives on provoking negative emotions like dread, disgust, and terror. There’s growing evidence that experiencing fear in a controlled environment can be therapeutic, but no one actually watches Saw or Terrifier for self-improvement. They’re here for entertainment, and the science of why people enjoy these negative emotions is still a developing field.

In a 2022 Atlas Obscura story on fear, cognitive scientist Marc Anderson offered an intriguing theory about why people derive pleasure from jump scares, characterizing “fun” as a “meta-cognitive signal that the brain produces when we learn something faster than expected.” Human beings enjoy novelty, and when we process a sudden scare, our brains reward us for learning fast.

Behind the camera, crafting those jolts of terror is no easy task, says Stephen Cognetti, the writer and director behind the Hell House LLC franchise.

“Before I even jump into a script, I want to have a few scares,” he says. From camera angles to pacing, he begins every project with a precise idea of how these scenes will be filmed. “I’m very controlling about it because even in the editing process, one frame too much or too soon is just—it’s not right, it doesn’t work. I hate when I see a scare I’ve done that was edited by someone else, and they held onto something too long or too short.”

Cognetti, who aims for strategic, well-crafted shocks, compares an effective scare to a rollercoaster ride—a slow build to a sudden drop—and also to comedy, “where there’s a setup and a punchline and a payoff.” Of course, some punchlines elicit more of a groan than a laugh.

“I always say that you can make anybody jump if you just have a cat jump out of a closet,” says Cognetti. “That’s cheap, it’s easy, and I think audiences will get that jump but they won’t appreciate the scare afterwards. They won’t respect it.”

The jump scare’s reputation as a cheap tactic often comes up in discussions about recent “elevated horror” or “post-horror” movies such as Hereditary, The Witch, or Get Out, which explore more serious themes than, say, Scream. Critics praise these films for avoiding trashy shock value, but the truth is they still include jump scares. They just deploy them in unexpected ways.

According to David Church, author of the book Post-Horror: Art, Genre, and Cultural Elevation, elevated horror movies are often structured to disrupt our expectations. Modern audiences are acclimated to seeing a high volume of scares, to the point where “it becomes like a game the viewer plays with the director over where the jump scare’s going to come.” But post-horror movies are “minimalistic and austere,” using jump scares sparingly—and imbuing them with more narrative weight.

For instance, the biggest shock in Hereditary comes when a main character leans out of a car window and gets decapitated by a telephone pole. It’s a scream-worthy surprise, but it’s also a traumatic event with far-reaching consequences for the other characters. It’s the polar opposite of a cat jumping out of a closet.

Church also says that post-horror films “tend to deny audiences the jump scare as a reliever of tension,” embracing open-ended narratives and remixing classic horror tropes through an art cinema lens. For viewers who expect horror movies to be “smoothly oiled machines for generating jump scares,” he says, this ambiguity can be frustrating, which explains the divisive reactions to experimental films like Skinamarink and In A Violent Nature. Riffing on familiar subgenres (haunted houses and rural slashers, respectively), these movies both have extended periods where very little happens, elongating the buildup to a scare that may or may not arrive. To some viewers, they’re clever innovations in ambient dread. To others, they’re just a snoozefest.

Carrie’s finale allowed its audience to let off steam, punctuating the end of a tragic story. This kind of tactic still works, but after decades of Screams and Halloweens and Evil Deads, the next obvious progression is prioritizing quality over quantity. Instead of provoking shock for its own sake, a new generation of filmmakers are using momentary terror to create a more lasting impact. Post-Horror author Church highlights the success of the recent elevated horror indie hit Longlegs as proof that audience tastes are expanding, signaling a desire for deeper emotional payoff alongside the old-school scares of commercial hits like Alien: Romulus or Terrifier 3.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook