The Long, Surprising Legacy of the Hopkinsville Goblins

Or, why families under siege make for great movies.

One main theme of Steven Spielberg’s 1993 classic Jurassic Park may be that amusement parks are incredibly hard to operate, but an equally important lesson of that film (and the Michael Crichton book on which it is based) is that monsters bring families together. Alan Grant has no interest in having children with Ellie Satler, at least until he has to rescue the grandchildren of the park’s founder. They form a makeshift family and the rest is cinema history. Families under stress are a recurrent feature of Spielberg’s movies, from 1977’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind to the 2005 adaptation of War of the Worlds, and the countless films they have inspired. Fractured or broken, they come back together as something monstrous or terrifying emerges, re-binding through shared adversity. Spielberg, who was himself deeply affected by his parents’ divorce, seems to ask: What kind of monster or world-shattering event would be enough to keep a family together? So one can see why he might have been attracted to the story of the Hopkinsville Goblins.

The story comes to us from the local newspaper Kentucky New Era, which, on August 22, 1955, reported strange goings-on the previous night, eight miles north of Hopkinsville, Kentucky. At about 11:00 pm, two cars arrived at the local police station, blasting out of the night filled with at least five adults and several children, all of whom were highly agitated. “We need help,” they told the police. “We’ve been fighting them for nearly four hours.”

Once they’d calmed down enough to talk, they unfurled a strange story. One of the men, Billy Ray Taylor, had been visiting from Pennsylvania. At one point, he went outside to fetch water from the farm’s well. As he walked through the failing light, he saw a circular-shaped object hover through the air before coming to rest in a nearby gully.

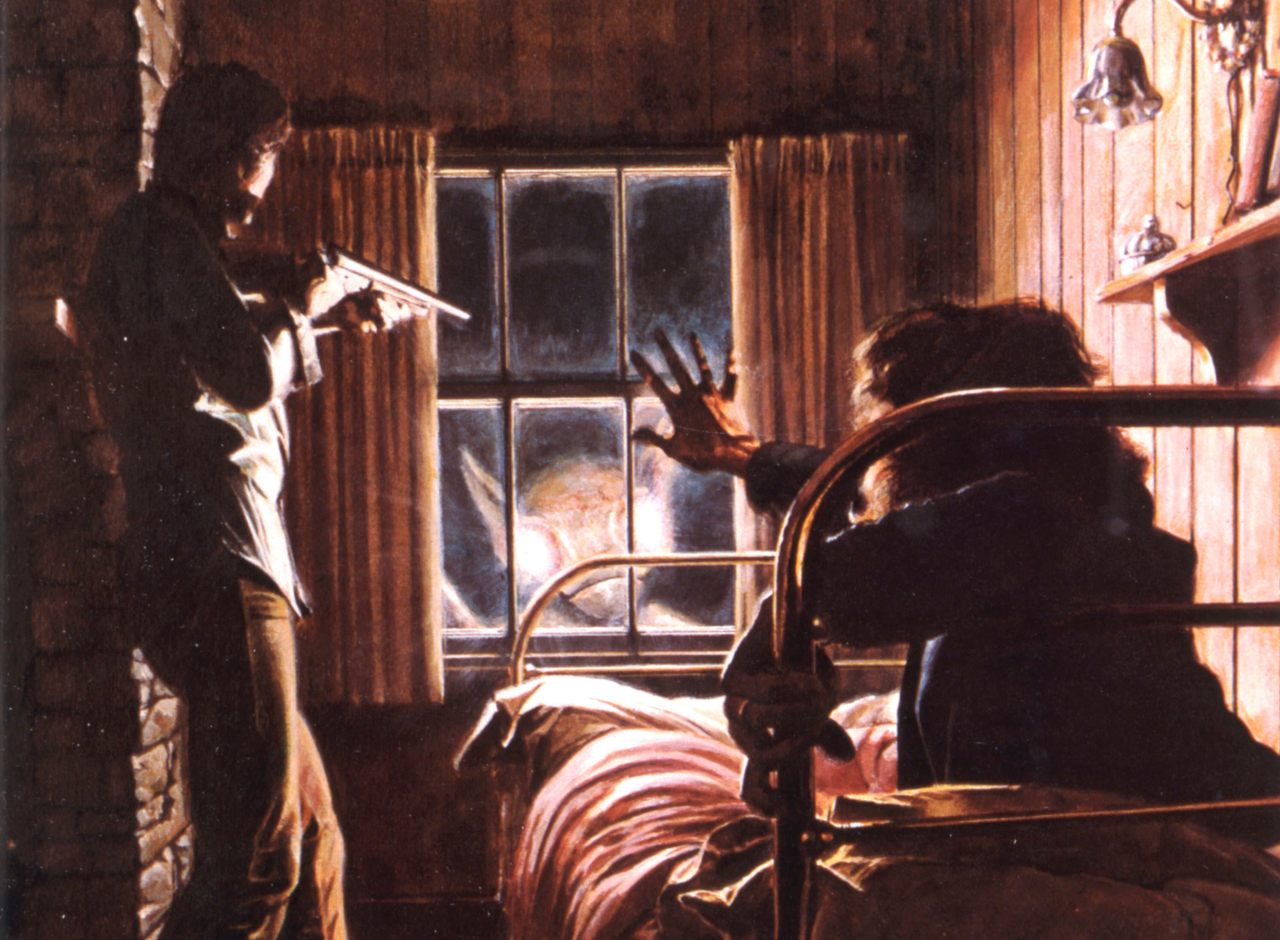

Concerned, Taylor retreated inside and returned with a shotgun to investigate. As he walked into the gloom, a strange, goblin-like thing with glowing eyes appeared and moved toward him. It had “huge eyes,” and hands out of proportion with its body, and looked to be wearing some kind of “metal plate.” Taylor retreated to the house yet again and grabbed a .22 caliber pistol, while Lucky Sutton grabbed a shotgun and joined him.

A creature—whether it was the same one, they didn’t know—appeared in the window, and Sutton unloaded his shotgun at it, blowing out the window screen. When they went outside to see if they’d hit anything, Taylor felt a “huge hand” reach down from the low roof above and grab his hair. He pulled away and the two men went looking for their quarry. They found one creature in a tree and another on the roof of a nearby house. Sutton fired another shotgun blast at one, which knocked it down but didn’t appear to have done serious damage. At that point, the goblins, as the family described them, disappeared. Barricaded inside once again, the families waited for a chance to escape, at which point they drove like hell for the police station.

The police who arrived on the scene found no goblins, no footprints of anything goblin-like, no flying saucer full of goblins, no evidence that anything had landed nearby. They found just a screen with a shotgun hole in it. And, despite all the excitement, that was it. Except it wasn’t. Not by a longshot.

Most skeptics (and pretty much anyone who’s taken a serious look at the story) now agree that what the families saw that night was most likely a pair of great-horned owls. Many cryptids and alien sightings, it seems, can be traced back to a strange encounter with wildlife in an unfamiliar setting. It seems plausible, for example, that the initial mothman sightings were a crane, and many supposed chupacabra sightings have been revealed to be coyotes or dogs. (In fact, as I write this, a new study in the Journal of Zoology suggests that Bigfoot sightings correlate with increased black bear activity.) We’ve already examined here how much of the lake monster mythos might simply be lake sturgeon: an animal that arises from a natural landscape in a way we’re not used to. And rather than accept that the natural world is sometimes just strange, supernatural or extraterrestrial explanations somehow make more sense to folks. What makes the Hopkinsville incident particularly noteworthy is its strange aftermath. This story, little known outside the world of ufologists and cryptozoologists, ended up having a massive impact on American, even global, pop culture.

On the heels of the massive success of Spielberg’s Close Encounters of the Third Kind, Columbia Pictures wanted a sequel. He was wary, but didn’t want Columbia to make one without him. For inspiration, he turned to J. Allen Hynek. He was an astronomer who’d been brought on by the Air Force to advise Project Blue Book, the umbrella investigation into unidentified aerial phenomena (UAP). Hynek started out as a skeptic, and helped the Air Force come up with alternative explanations for supposed UAP sightings. But gradually he came to believe in their existence and publicly criticized the Air Force for refusing to accept his conclusions. Hynek had advised Spielberg on Close Encounters (the film’s title itself derives from a classification system that Hynek invented); in the course of their discussions, Hynek told Spielberg the story of the Hopkinsville Goblins.

Spielberg wrote a treatment based on the incident, and turned to filmmaker John Sayles for a script, Night Skies. To flesh out the plot, Sayles gave the aliens that besieged the family their own personalities. Scar was a particularly evil one who could kill things simply by extending a long, bony finger that emitted a glowing light. Buddy, on the other hand, was nice.

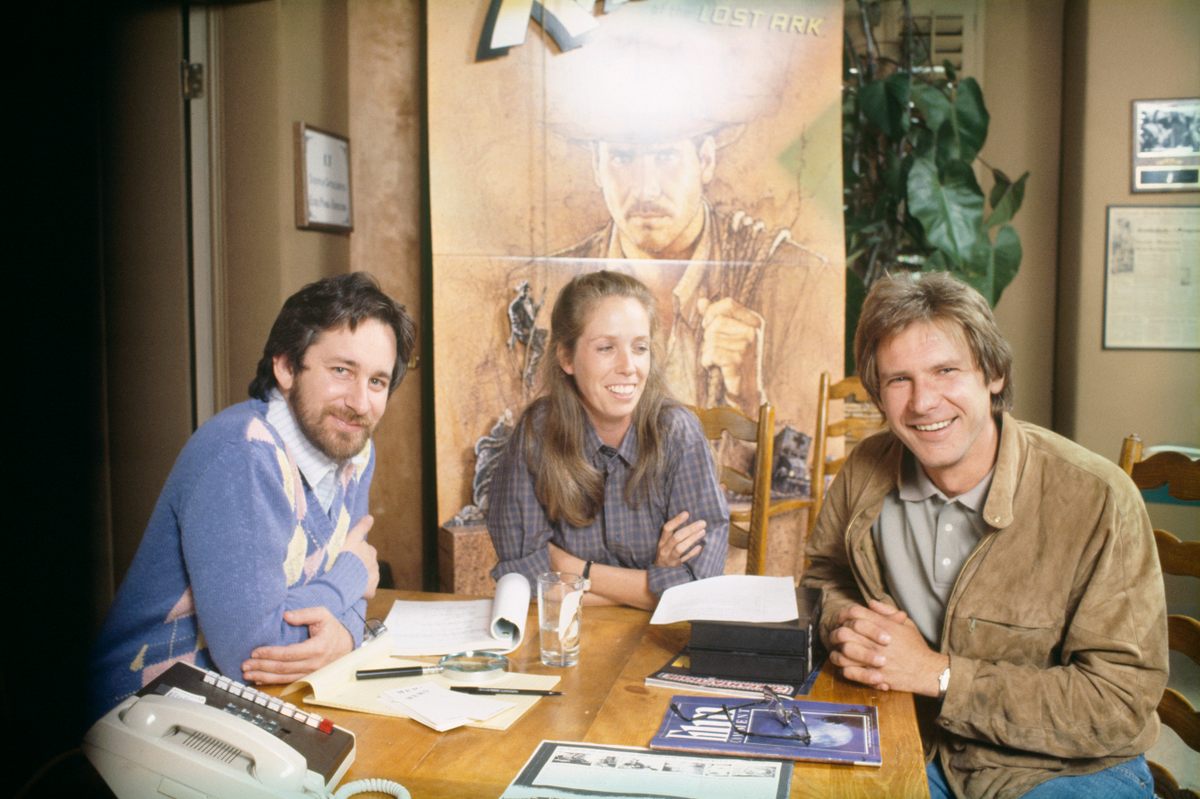

Spielberg, at some point, began having second thoughts about turning the Hopkinsville incident into a horror action movie. He was shooting Raiders of the Lost Ark and found himself wanting to return to the “tranquility” of Close Encounters. He shared Sayles’s script with screenwriter Melissa Mathison, who seized on Buddy alien, along with Scar’s light-emitting finger, and discarded the rest. She wrote an entirely different kind of alien movie, involving a sympathetic alien and a small child: She called it ET and Me.

E.T. the Extra Terrestrial (as it came to be called) was not the only film to emerge from Spielberg and Sayles’s unproduced script. Like a wet Mogwai, Night Skies continued to spin off new ideas and films. Gremlins, for which Spielberg acted as executive producer, also borrowed heavily from its ideas, with magical gremlins replacing the aliens and “Scar” evolving into the evil version of friendly Mogwai, Stripe. The concept of a family under siege from supernatural forces found its way into another script Spielberg ended up cowriting, Poltergeist. As the storied legacy of Night Skies circulated through Hollywood, its influence continued to be felt beyond films Spielberg was involved in: the B-movie Critters, M. Night Shyamalan’s Signs, 2023’s No One Will Save You.

These stories about monsters and ghosts and aliens threatening families—that must come together to fight them—struck a chord in Ronald Reagan’s 1980s, when many felt as though the institution of the family was under attack from all manner of corrupting influences. The strangest and most visible form of this happened in 1983, when the mother of a child who attended McMartin Preschool in Southern California began alleging that bizarre and extreme forms of child abuse were happening there, including Satanic rituals, human sacrifice, and supernatural events. A moral panic surrounding the threat of “Satanic” preschools gripped the nation; ultimately hundreds of people were thrown in jail based on nothing more than the coerced testimony of preschoolers. The suburbs, a hysterical public came to believe, were literally under attack by dark forces.

In such a landscape, the narrative of monsters at the edge of the homestead and family bonding in its defense was an increasingly appealing narrative. Spielberg’s films clearly tapped into this anxiety, turning it into horror, sci-fi, and, in the case of Gremlins, comedy, literalizing those inchoate fears into genre entertainment. Film critic J. Hoberman explains in Make My Day: Movie Culture in the Age of Reagan that although they may seem tonally opposed, “Poltergeist and E.T. both treat what Spielberg called ‘the lifestyle of suburban America’ as essentially apocalyptic, TV normality refracted through the Book of Revelation. A photo-realist appreciation for the nuances of tract-house life barely conceals the hysteria that underlies the two movies (not to mention Close Encounters). In Poltergeist, the suburb (which Spielberg would maintain was based on Scottsdale, Arizona, where he grew up) has been constructed atop a graveyard; in E.T. it is a pit stop for a sentient being from outer space.” As the director himself would later put it, “Poltergeist is what I fear and E.T. is what I love. One is about suburban evil, and the other is about suburban good.”

But well before suburbs, even before the country was founded, the settler culture of European Americans cleaved to the story of invasion of the home by alien forces. It is, in many ways, the central founding narrative of what would become the United States. In 1676, the Massachusetts Bay Colony was attacked by combined forces from the Wampanoag, Nipmuc, and Narragansett peoples, who raided the town of Lancaster. During the attack, the village minister’s wife, Mary Rowlandson, was taken captive; she was held for three months before release. Her subsequent record of the ordeal, The Sovereignty and Goodness of God, Together with the Faithfulness of His Promises Displayed: Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, became a bestseller upon its publication in 1682.

Rowlandson’s book spawned a genre—the captivity narrative—that became, as historian Richard Slotkin wrote in his 1973 book Regeneration Through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600–1800, “the first coherent myth-literature developed in America for American audiences.” Stories of the abduction and restoration of white settlers by Indigenous Americans, he noted, completely dominated “the list of frontier narratives published by Americans between 1680 and 1716, replacing narratives of soldierly exploits in the sermon-narrative literature.” They were stories in which homesteads were seen as under perpetual attack from outside, with only the mercy of God and the rifles of strong, masculine patriarchs could keep the family together.

These narratives re-emerge in the popular American consciousness at various moments. If there is a single, enduring myth that keeps white American culture together, it is that the home is perpetually under siege, and defense of the home helps bind the family. After World War II, when a generation of men who’d fought overseas came home to domestic life and desk jobs, a yearning for masculine began to express itself in pop culture. One form this took was a newfound fascination in Bigfoot; another was in frontier narratives of “cowboys and Indians,” including a rebirth of captivity narratives. Perhaps the most famous of these, John Ford’s 1956 The Searchers, in which John Wayne must rescue his niece (played by Natalie Wood) from a band of Comanches.

That story was not far from John Sayles’s mind when he was writing Night Skies for Spielberg. When he was designing his alien antagonists, he named his villain after Henry Brandon’s character in The Searchers: a Comanche chief named Scar.

Colin Dickey is the author of five books of nonfiction, including Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places, and, most recently, Under the Eye of Power: How Fear of Secret Societies Shapes American Democracy. He also hosts Atlas Obscura’s Monster of the Month.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook