Could an Infamous WWII Bunker Become a Symbol of Peace?

The tunnels under Okinawa’s Shuri Castle should be preserved as a reminder of the costs of war, advocates say.

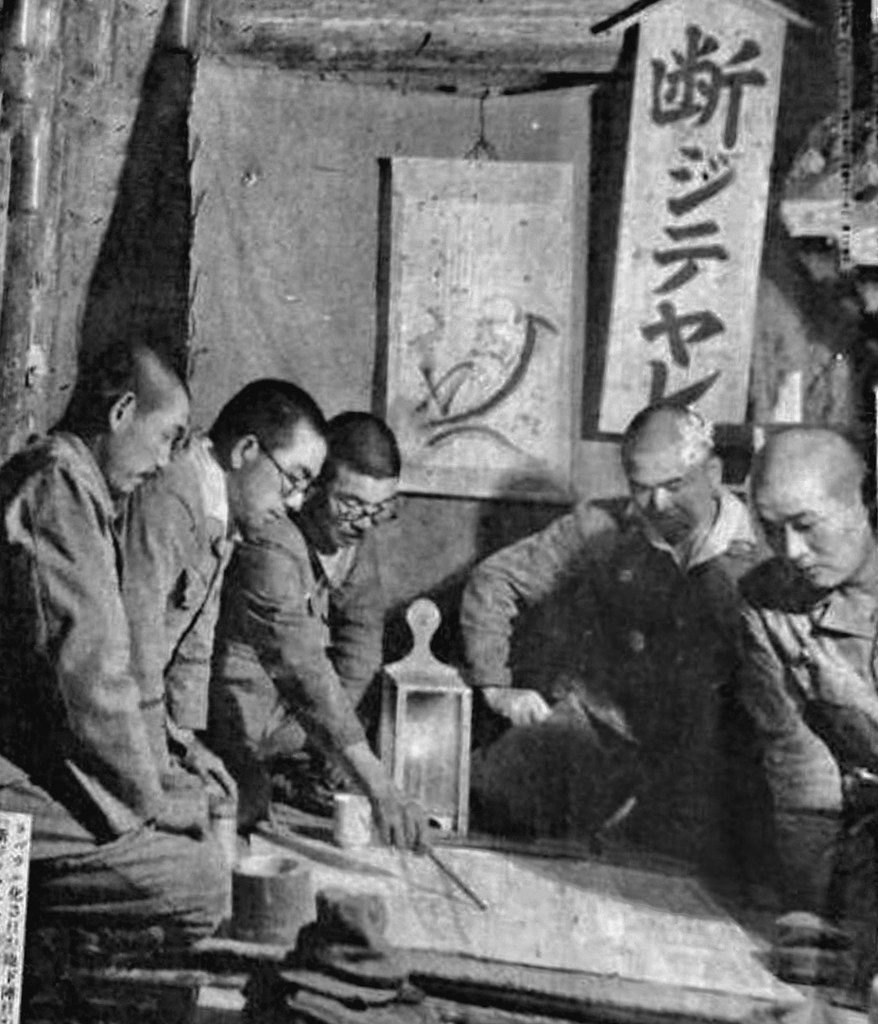

At a nighttime command conference convened on May 21, 1945, Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima, commander of the 120,000-man Japanese 32nd Army in Okinawa, decided that his troops would have to evacuate their underground headquarters deep beneath historic Shuri Castle and retreat further south. The ferocious Battle of Okinawa had been raging for eight weeks, and Ushijima’s well dug-in Japanese fighters had made American forces pay dearly for every small gain thus far. But by late May, US army and marines were closing in on the beautiful ancient capital of Shuri, where Ushijima had established what he had promised would be his final line of defense.

On May 27, under the cover of darkness and a tight blanket of secrecy, troops of the 32nd Army fled from Shuri, leaving noncombatant Okinawan civilians to fend for themselves. Unprotected from naval, aerial, and artillery bombardment, more than 100,000 Okinawans—one-quarter of the population—perished in the fighting or committed suicide under orders from the Japanese military instead of surrendering. The large underground headquarters where these fateful decisions were made, called Dai 32 Gunshireibu-go, or 32 Gun-go for short, survives in silent testimony to the horrific events. Now, over 75 years later, a motivated group of people, including one of general Ushijima’s grandsons, is working to preserve the cramped tunnels and ensure that the memory of what transpired there is not forgotten.

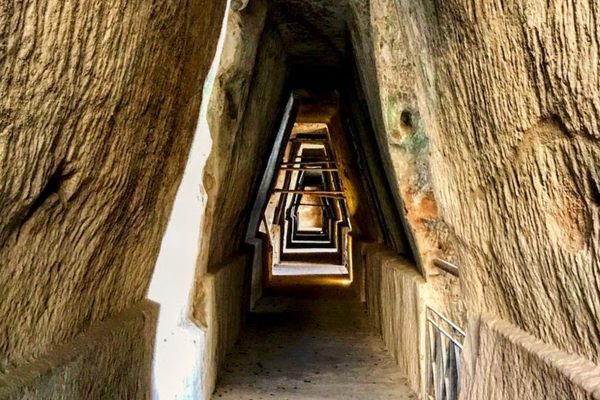

Today, the five main entrances to the underground headquarters are overgrown and damaged but still visible, along with a few concrete remains which protrude above the ground surface. Everything significant is hidden from daylight, a dank and inaccessible crypt. Although an information board in Shuri Castle Park marks the site, few tourists—few local residents as well, in fact—seem aware of the relic’s existence or significance. After General Ushiima’s orders to abandon the headquarters on May 27, 1945, demolition charges were detonated to block the entrances and deny American forces access. The site has remained inaccessible to the public since then, marked only by locked gates. Only a few people have entered the tunnels since 1945, including construction workers who installed steel reinforcement in some sections in the 1990s, as well as Okinawa Prefecture staff conducting safety evaluations, occasionally accompanied by small camera crews to document the inspections.

Japan is dotted with massive defensive installations like this built by the Imperial Japanese Forces prior to and during the Second World War. Most are too stoutly built to be easily demolished and all are fraught with controversy, standing in ignominy and obscurity. The particularly horrific wartime experience of Okinawa, however, as well as its postwar occupation by the US until 1972 and the large proportion of land still used for U.S. military bases, has given rise to an extremely powerful local peace movement unique to the prefecture.

In most parts of Japan, the threat of harassment and violence from right-wing ideologues who oppose any attempts to paint the Japanese military in a negative light makes such an honest public reckoning of wartime history impossible. But in Okinawa, there is a publicly supported peace museum; several memorials marking sites where civilians died in great numbers; a shrine honoring the souls of all who died, even enemy combatants; and an official curriculum of peace studies which begins in elementary school. In this environment, the underground headquarters has the potential to become a uniquely powerful vehicle for teaching younger generations about the horrors of war.

The movement to preserve and reopen the tunnels to the public, called the Association for the Preservation and Opening of the 32nd Army Underground Headquarters, is spearheaded by Hojun Kakinohana, an 86-year-old former prosecutor and emeritus law professor at Ryukyu University in Naha. Born and raised on the small Okinawan island of Miyako-jima, where he was a middle school student when the war ended, Kakinohana now lives in Shuri.

“Although I had known since my university years that an underground headquarters existed, I didn’t know the actual location until I was shown the entrance while peace-walking ten years ago,” he says, referring to organized walking tours to visit battle sites and memorials to learn about their history. “I was surprised that it was not open to the public. I realized that it is the site of tragic and inhuman decisions to sacrifice the civilian population, including giving drugs and hand-grenades to the injured and ordering them to commit suicide.”

Kakinohana spent several formative years in the United States, obtaining his doctorate in law at Stanford University as a Fulbright scholar and undertaking additional study at the University of Michigan. His focus was on human rights issues, and this shapes his view of 32 Gun-go and the military evacuation. “The Japanese military did not inform the public, because they truly did not consider the lives of Okinawans to be valuable. Because of our history and different culture and dialect, Okinawans were considered lesser humans by the Japanese government. Even today, the political system never makes it clear whose protection should be prioritized. During the war, the Japanese military considered its own protection to be paramount. I want people to understand that they considered the sacrifice of the lives of Okinawans to be acceptable for this.”

Shuri Castle is an unparalleled symbol of Okinawan culture and history. The castle, completed in the 14th century and designed to emulate at a smaller scale the Forbidden Palace in Beijing, sits atop the most defensible hill in the region with panoramic views of the surrounding terrain extending to the ocean in three directions. “At the time it was built, the Japanese military were aware that Shuri Castle and other monuments were of historical value, but the hill on which they stood was considered more important as military bases,” says Makoto Nakamura, the Executive Director of the Friends of the Okinawa Peace Memorial Museum, one of the most knowledgeable people on the history of 32 Gun-go. “Siting the headquarters underneath, it was a pragmatic decision based on military needs alone.”

Using only picks and shovels, soldiers, and conscripted laborers, including local high school students, began construction of the underground headquarters tunnel network in December of 1944. Work continued until shortly before the Battle of Okinawa began in early April 1945. The underground complex is composed of five tunnels which branch from a long central corridor, with a combined total length of about two-thirds of a mile. At its greatest depth it lies about 100 feet below Shuri Castle. Just six feet wide by six feet high, with suffocating heat, moisture, and poor air quality, the headquarters was nevertheless fully equipped with the facilities necessary for battle and command. The tunnels contained barracks and operational facilities for about 1000 officers, enlisted soldiers, workers, students, and others, including, by reliable accounts, conscripted sex workers. There were offices and kitchens and mess facilities, as well as living spaces. Large suites and conference rooms were provided for the commanding officers.

By the end of the Battle of Okinawa, Shuri had been reduced to a moonscape and the ancient stone walls of Shuri Castle itself were rubble. Only charred stumps remained of its sacred centuries-old forests, and the entrances to this dark, underground world were nearly obliterated.

Shuri Castle has suffered destruction by fire five times over its history and has been repeatedly rebuilt. After the Battle of Okinawa, a meticulous restoration of its main structures was finally completed in 1992. In October 2019, however, a large fire tragically destroyed the castle’s opulent seiden, or main hall, and several other important buildings. Rebuilding is currently underway and scheduled to be completed in 2027. The significant attention to Shuri and the large allocation of government funds for rebuilding the castle have helped focus the energies of those seeking to preserve 32 Gun-go.

“Right now there’s a lot of public interest in restoring Shuri castle,” says Shunji Fukumura, an Okinawa-based architect who is involved in planning for making 32 Gun-go publicly accessible. “But we believe the Dai 32 Gunshireibu-go is essential to understanding the fate of Shuri Castle itself. A lot has been written about Ushijima and the headquarters, but to really grasp what happened it’s essential for people to be able to see the place with their own eyes, to physically experience it like at Auschwitz or the Atomic Bomb Dome in Hiroshima.”

Making the cramped, partly collapsed tunnels accessible presents tremendous technical challenges. Fukumura has proposed constructing a new, more spacious concrete tunnel alongside the original that would allow people to see key parts of 32 Gun-go, while maintaining the original structure. Okinawa Prefecture has been very supportive of these restoration efforts, convening an active committee to study and publicize the issue, and advocates hope that the project can be piggybacked on to the well-financed restoration of Shuri Castle.

One of the more surprising supporters of the efforts to restore and open the underground headquarters is Sadamitsu Ushijima, grandson of Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima. He is a recently retired elementary school teacher living in Saitama, near Tokyo. “When I was a child, my family presented my grandfather to me as a great and kind man.” By age 13, Ushijima says, he had learned more about the war and the Battle of Okinawa and began to think more critically about his grandfather’s role. But he avoided going to Okinawa until 1993, when he was in his 40s.

On that trip Ushijima made time to visit the Peace Museum and attend a peace walking tour of war sites. “Of course, I didn’t tell anyone of my connection to the Battle of Okinawa,” he says. “But the guide noticed that my name differed from my grandfather’s by only one character. I felt as if I had been discovered.” He saw the actual written orders his grandfather had made for his troops to fight to the end and to sacrifice their lives through suicide attacks, even though their defeat had already been sealed. He saw the underground bunker at Mabuni, at the extreme southern end of the island, where his grandfather himself committed suicide as US forces closed in on June 22, 1945. “I realized that it was time for me to learn more about my grandfather, and I began spending more time in Okinawa,” he says. “I want people to understand the terrible unnecessary human loss of life that occurred because of my grandfather’s orders.”

More than 75 years have passed since the Battle of Okinawa, but that has made this reckoning more urgent, not less. As Hojun Kakinohana put it, “The human lessons we can learn from this headquarters are vastly more important than what Shuri Castle has to teach us. It’s about the value of life and the uselessness of war. I’m in a hurry to see it reopened and hope it will be designated a world negative heritage site. There are not many of us who experienced that war left to tell our stories. We’ll be gone soon. So I’m in a hurry.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook