About

The tiny, wood-framed house stands alone beside a dry stone wall next to an unpaved road. Known as Innis (or Ennis) House, it is now part of the Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park. The road that runs beside the house is the infamous Sunken Road, the site of the bloodiest military engagements of the First and Second Battles of Fredericksburg during the U.S. Civil War. Many of the over 12,000 Union casualties, of which roughly 1,900 were KIA, during the First Battle of Fredericksburg died at Sunken Road.

Innis House is a modest building of only three rooms and 1-½ stories. Built sometime before 1850, the house was purchased by Martha Stephens in April 1861 and occupied by Stephens' son, John Innis, and several other presumed family members. Stephens also owned and resided in the house located next door. At the time of the Civil War, the property was on the outskirts of Fredericksburg in an area known as Marye's Heights.

On December 13, 1862, nearly 30,000 Union soldiers descended on the Sunken Road. They met and engaged 10,000 Confederate soldiers, who were sheltering behind the stone wall bordering the road and positioned on the surrounding heights. Innis House's residents had wisely decamped to parts unknown, and Confederate sharpshooters occupied the house's upper half-story. The house found itself on the battle's frontline and in the direct crossfire of the combatant armies.

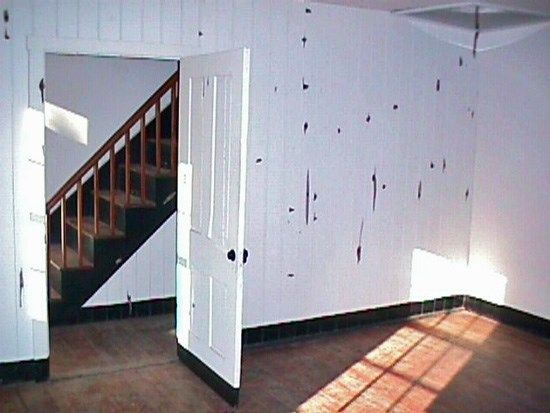

By day's end, bullets and mortar shrapnel perforated the house from top to bottom. In writing about the assault on Sunken Road, Confederate General Lafayette McLaws said that Innis House "had no space as large as two hands on it that had not been pierced." To add insult to injury, the sharpshooters occupying the house left graffiti scrawled on the upper-story walls.

After the war, Innis House resumed its duty as a domicile. Although Stephens replaced some of the damaged exterior wood, bullets remained embedded in the timber frame. The tiny house continued as a private residence until 1969 when the U.S. National Park Service (NPS) acquired it and the surrounding property. In 1985, after lengthy exterior restoration, work to return the house's interior to its wartime appearance commenced. By removing modern wood partitions and peeling off multiple layers of wallpaper and newspaper from the interior walls, conservationists discovered dozens of bullet holes and scars from artillery damage—preserved for almost 125 years. Newspaper pages also covered the second-story walls, and removal revealed wartime graffiti, including names, regiments, and the pencil drawing of a bird in a frame. Rather than repair or replace the damaged walls, the NPS left them unaltered. More than a century later, it is still shocking to see such graphic and tangible evidence of the 1862 conflagration on the Sunken Road.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The Park Service opens the Innis House to visitors on special occasions such as Memorial Day weekend and the battle anniversary. When the park is open, between sunrise and sunset every day, visitors can easily view the interior damage through the first-floor windows.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

January 6, 2022