About

In Middletown, Rhode Island—across from a post office, behind a Christmas paraphernalia store and kitty-cornered from a budget motel—lies a 30’ x 40’ cemetery dating to 1801 and the burial place of Colonel George Irish.

A dry-stack stone wall protects the eighteen-headstone lot from the surrounding bustle. The carved remembrances are faint, with only some words and names that remain legible. Some stones have tilted with the settling of the earth over the centuries; some bear large well-worn holes. John “Walt” Walters, owner of the headstone restoration business Graveyard Groomer in Indiana, has seen such holes, but remains baffled by their cause. Cheryle Caputo, a co-founder of the volunteer group Friends of Burial Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts believes that they’re bullet holes. Because the headstones are likely carved from slate—which was more common in the region at the turn of the nineteenth century than the marble or granite later used for carvings—its flinty nature would explain the irregular shapes of the holes. And who knew that a national corps of “graveyard rabbits” exists who document and restore headstones, and study genealogy and burial customs? Their moniker is drawn from an eponymous nineteenth-century poem by Frank Lebby Stanton, the first professional columnist for what became the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

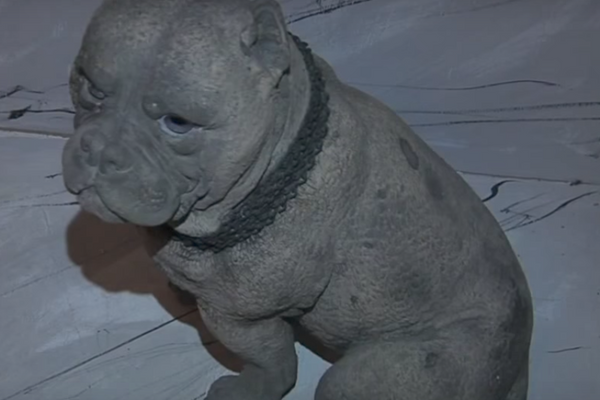

As to the past of the cemetery itself, George Irish was born in Middletown in 1729; his Rhode Island roots date back to the mid 17th century through his maternal line, his paternal ancestry is English traced through his great-grandfather who immigrated to Plymouth, Massachusetts. His tombstone has a face carving that brings to mind Ebenezer Scrooge’s vision of Marley in the doorknocker. Irish was an influential man, owning the West Indies trade brig Friendship and farms named Peleg Kinyon in Hopkintown, Redwood Farm in Middletown, and Benja Clarke in Stonington, Connecticut. He was also a grain merchant. Through his successes he helped fund the Revolution with a loan of 3,257 pounds sterling; he worked directly with George Washington and served as a colonel for the First Rhode Island Militia in 1776-77. In his father Jedediah Irish’s will he was left “Six hundred Pounds old Tenor & all my Shoe Makers Tools.” It would seem that George exceeded his father’s more humble expectations.

Irish fathered 11 children, losing two sons to drowning accidents. There’s lovely non-legalese language in his will (written just 7 days before his death), including referring to his wife, Sarah, as his “Beloved” and descriptions of tracts of land bounded by a barn, a stream and chestnut trees. His children and grandchildren bore nostalgic names like Bartholomew, Hannah, Martha and Patience; there’s also an aunt named "Thankful" in his family tree. He left great wealth in the form of land to most of his children, but curiously only $100 to his eldest child, Mary—to be paid 2 years after his death. Perhaps most unusual for the era, he granted freedom to his “Black man Jupiter” and promised a home for him with whichever of his sons he chose to live with.

Aquidneck Island, home to this pocket graveyard, has 181 registered cemeteries in Newport, Portsmouth, and the rest of Middletown, many of which are large and quite grand considering its Revolutionary War lineage and Gilded Age wealth. That this wee spot has survived in this commercial district is a testament to the respect Rhode Islanders have for their history and its model citizens. Flags and flowers are still brought to the graves.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

High Street, across from the Middletown, RI post office and Residence Inn

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

March 11, 2015