About

Across the waters from the Cannaregio district of Venice, a red-walled island houses the city's dead. New by Venice standards, the cemetery has been the only official Christian burial grounds since the early 1800s.

When the independent Republic of Venice fell to Napoleon in 1797, the residents were forced to endure the city changing-demands of the new Empire, which included removing the gates to the Jewish ghetto (which had previously been closed nightly), and by declaring that the dead could no longer be buried within the city. The existing tradition had been to bury the dead in the churches or below city paving stones, which was less than sanitary by the standards of most cities of the era, and most definitely a problem in a city which floods several times annually. In their defense, victims of Venice's many plagues were deposited on remote islands, often before they had actually expired.

The modern island is composed of two smaller islands, joined along the canal in 1836. It was named for the existing church dedicated to the archangel Michael designed in 1469 by Mauro Codussi, the famous architect who had his hand in many of the Venetian Renaissance churches and landmarks of the era, including the enormous clock tower in Piazza San Marco. The church and chapel are adjacent to the entrance to the island from the ferry landing. The entrance to the cemetery is past the cloisters of the old monastery. The burial areas are divided into categories, with the majority devoted to Catholic graves. Smaller sections are for Greek Orthodox, for foreigners, and for Protestants. Small sections are dedicated to childrens' graves and for gondoliers. Jewish residents were buried separately in the Lido.

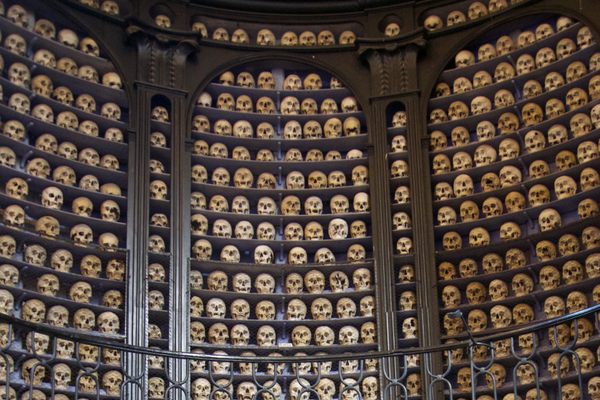

The grounds are green and expansive, covered in rows of modern tombstones, and dotted with statuary, trees, and occasionally a small family chapel or mausoleum. Parts are clean and well attended, other corners have fallen into disrepair. Walls form the ossuary where bones are retired after 10 - 12 years in the ground. This is a place of modern burials, and it has been noted that there are not many famous names to be spotted, but the composer Igor Stravinsky and poet Ezra Pound still call it home. Every year on the Festa dei Morti, or All Soul's Day (Nov 2), locals say mass in remembrance of the dead, and visit the cemetery en masse, and the ferry is free. Small traditional pastries called Fave, or Fave dei Morte (for 'beans' or "Beans of the Dead" in Italian) can still be found to commemorate the ancient tradition of eating and distributing beans to the poor during All Souls.

Visitors to the island should bear in mind that many of the burials on the island are recent, and locals may be in mourning. Modest attire and quiet voices are appreciated. Maps may be available in the cloisters if they are open.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

Take the vaporetto number 41 or 42.Photography is forbidden within the cemetery walls, so be discreet. Also, beware of the seagulls.

Flavors of Italy: Roman Carbonara, Florentine Steak & Venetian Cocktails

Savor local cuisine across Rome, Florence & Venice.

Book NowCommunity Contributors

Added By

Published

July 6, 2009

Sources

- Venice

- http://www.nytimes.com/1993/05/16/travel/venice-s-isle-of-the-dead.html?scp=4&sq=venice%20michele&st=cse

- Italy Heaven - San Michele Visitor Information

- http://www.italyheaven.co.uk/veneto/venice/sanmichele.html

- William Dean Howells, <cite>Venitian Life</cite>, 1883 (via Google Books)

- Description of Venetian Funeral, circa 1880, pg 286

- http://books.google.com/books?id=40MNAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA286&dq=venice+funeral+tradition

- <cite>Festivals for the Dead</cite>, New York Times, Dec 7 1881 (PDF)

- http://query.nytimes.com/mem/archive-free/pdf?_r=1&res=9A02E2DF163DE533A25754C0A9649D94609FD7CF

- Judi Culbertson and Tom Randall, <cite>Permanent Italians</cite>, (out of print but available used)

- http://europeforvisitors.com/venice/articles/to_die_in_venice.htm

- Hugh Honour, <cite>The Companion Guide to Venice</cite>, 1997 - pg 243