About

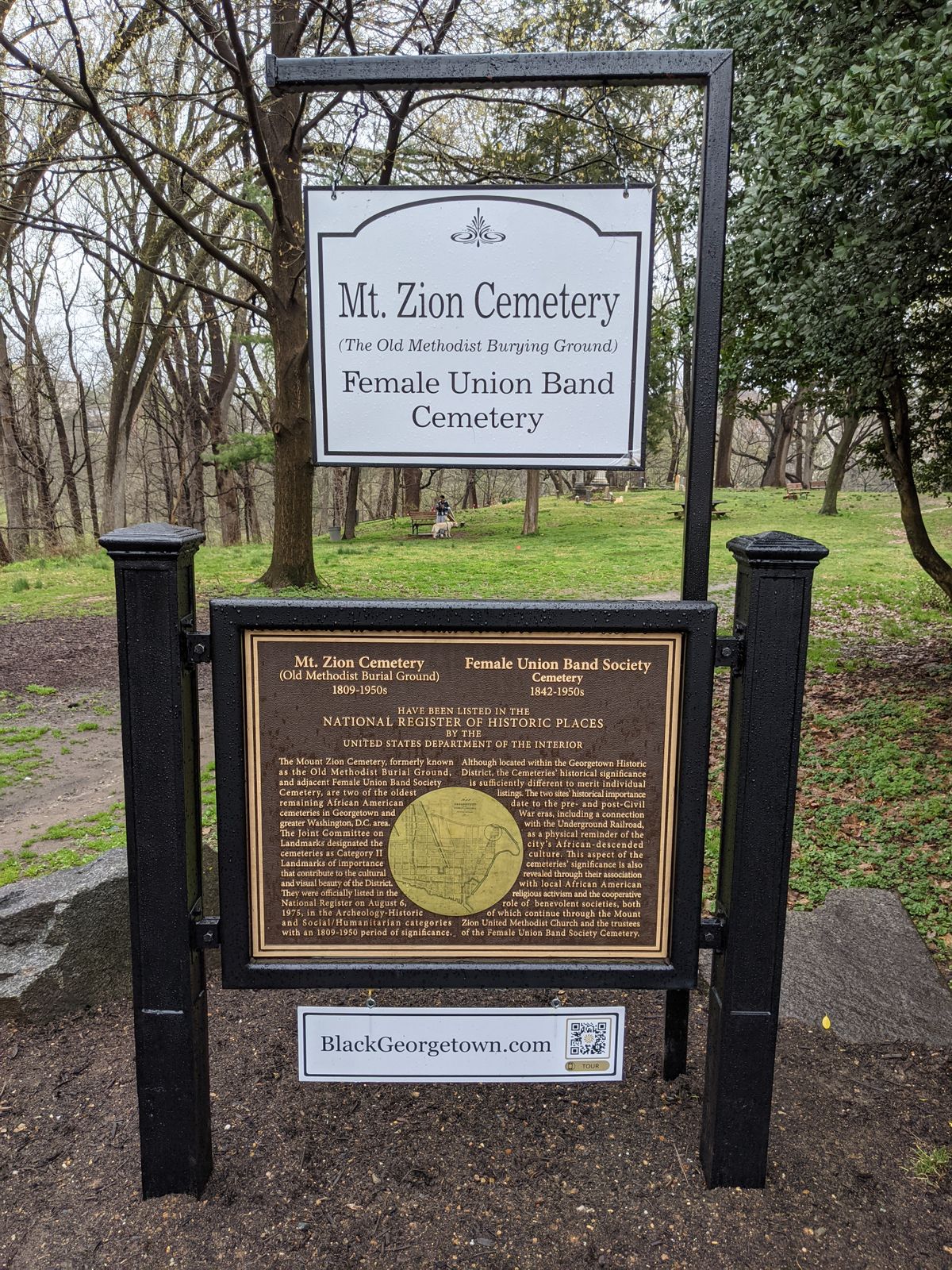

Tucked away in the corner of the Mount Zion Cemetery in the hills above Washington, D.C.’s Rock Creek, an unassuming outbuilding may have been a waystation on the Underground Railroad. It’s one of many Black history sites in the District nearly lost to midcentury redevelopment.

The hiding spot is a eight-foot-by-eight-foot windowless brick structure that was once used for wintertime corpse storage when the ground was too hard for digging. To have spent the night in such horrifying proximity to human-filled coffins speaks to the desperation that enslaved people must have felt for freedom.

Because of the clandestine nature of the Underground Railroad there is no written record of enslaved people sheltering at Mount Zion. Still, oral histories passed down through generations of Georgetown’s Black community have kept the site’s significance alive.

“This was a safe place for the slaves because it was deep in the woods and covered over so that it was only visible from one side” local historian Neville Waters told The Washington Post. “And since bodies of the dead were kept here, nobody would have thought to look inside.”

Enslaved people fleeing Virginia would have spent the night at the Mount Zion Cemetery before continuing north or west into abolitionist territory. Washington was not a destination, but a thoroughfare on the Underground Railroad. Some of the most prominent families in the city where slavery sympathizers, counting among their ranks the Alexanders’, Lee’s, and Peters’. Still, there were some allies in Georgetown who are said to have frequently left food and water out at the Mount Zion Cemetery for those escaping slavery.

Today the hiding spot sits unlocked and unmarked, obscure to all but a few locals. It’s something of a miracle that the site has survived at all. The cemetery closed in the 1950s, and within a decade it was lost beneath a tumble of vegetation. Many of the headstones were stolen, sanded down and reused anew. The few white graves at Mount Zion were exhumed and reinterred next door at the exclusive Oak Hill Cemetery alongside the many politicians and millionaires.

During the 1960s the plight of Mount Zion came to the attention of the Afro-American Bicentennial Corporation. The group undertook the first efforts to rehabilitate the dilapidated cemetery. Thickets were cleared, saplings pulled, and gravestones piled. The forest was pushed back and a small stairway was cut to provide access to the entrance of the cadaver storage building. A planned museum never materialized, but today the site is quiet park, and a partial-win for the preservation community.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

August 15, 2017