About

"On reaching the spot where the body had been devoured, a dreadful spectacle presented itself. The ground all round was covered with blood and morsels of flesh and bones, but the unfortunate jemadar's head had been left intact, save for the holes made by the lion's tusks on seizing him, and lay a short distance away from the other remains, the eyes staring wide open with a startled, horrified look in them. The place was considerably cut up, and on closer examination we found that two lions had been there and had probably struggled for possession of the body. It was the most gruesome sight I had ever seen. We collected the remains as well as we could and heaped stones on them, the head with its fixed, terrified stare seeming to watch us all the time, for it we did not bury, but took back to camp for identification before the Medical Officer. Thus occurred my first experience of man-eating lions, and I vowed there and then that I would spare no pains to rid the neighbourhood of the brutes."

-J.H. Patterson, "The Man-eaters of Tsavo", 1907

For nine months in 1898 workers on the British Kenya-Uganda Railway were terrorized, attacked, and eaten by two enormous lions. At least 35 people, and possibly as many as 135 (depending on the source), were killed by the stealthy lions named by natives "Ghost" and "Darkness."

The railway project was intended to link Mombasa, Kenya to Lake Victoria in Uganda in order to create a trade route for raw materials and British goods into Uganda. The project relied on the skills of thousands of imported Sikh laborers from British India along with local laborers. The lions were only one of many problems encountered during the construction process. To start with, much of the construction crossed through Masai tribal lands. In 1895, 500 workers were killed by Masai in retaliation for the alleged rape of two Masai girls.

Back in Britain, many saw the project as a colossal waste of money. At the House of Lords the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, groused about the lack of progress on the railway: "The whole of the works were put a stop to for three weeks because a party of man-eating lions appeared in the locality and conceived a most unfortunate taste for our porters. At last the labourers entirely declined to go on unless they were guarded by an iron entrenchment. Of course it is difficult to work a railway under these conditions, and until we found an enthusiastic sportsman to get rid of these lions, our enterprise was seriously hindered."

From March to December the two lions picked off workers. Efforts to barricade work camps failed, and the work crew became increasingly terrified.

Tsavo lions are different from savanna lions. They are exceptionally large, and the males are maneless. Their behavior in the wild is also different, and they may have become accustomed to seeing humans as easy prey following years of slave trains passing through their territory, where bodies of the dead were left where they fell.

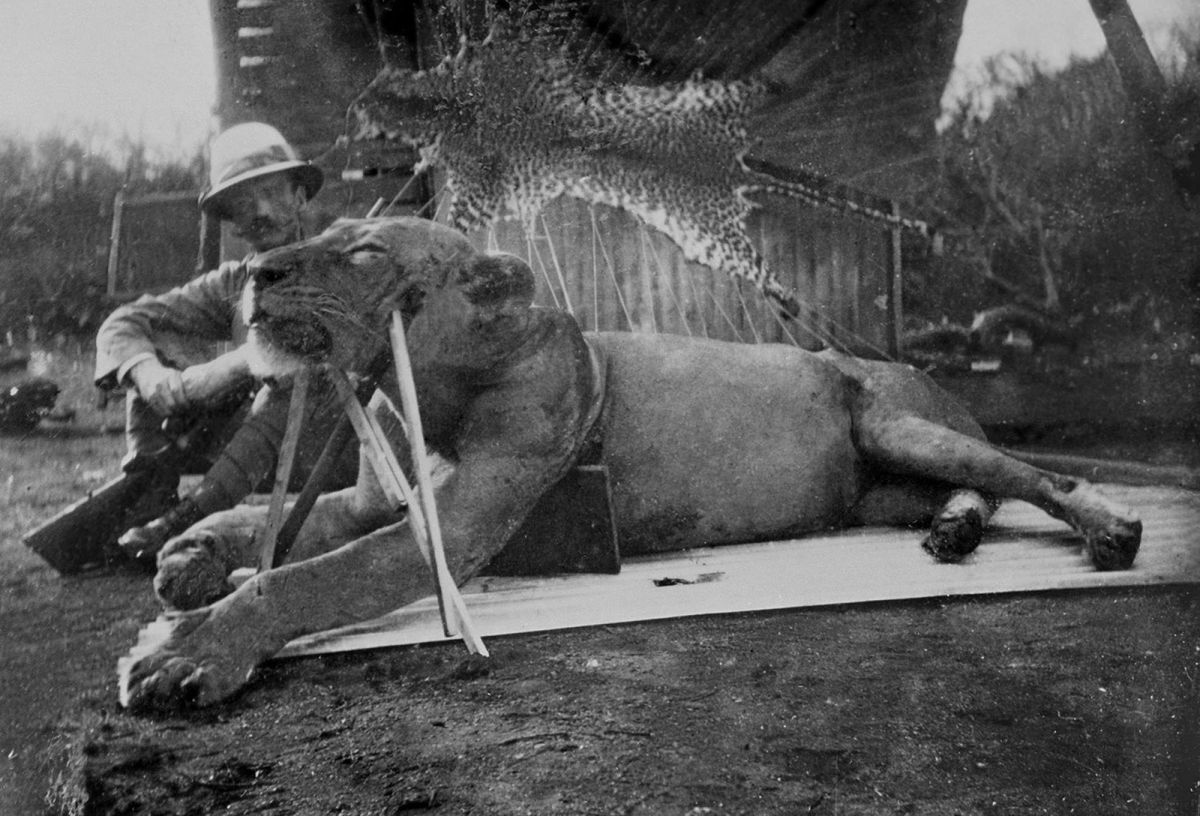

It fell to railway engineer J.H. Patterson to stalk and kill the man-eaters. Patterson was a skilled hunter, but not a professional marksman. He finally tracked and killed the first lion in December of 1898, and then shot the second lion three weeks later. It took 10 shots to kill the second lion. In his own words:

"...in a short while I heard the lion begin to creep stealthily towards me. I could barely make out his form as he crouched among the whitish undergrowth; but I saw enough for my purpose, and before he could come any nearer, I took careful aim and pulled the trigger. The sound of the shot was at once followed by a most terrific roar, and then I could hear him leaping about in all directions. I was no longer able to see him, however, as his first bound had taken him into the thick bush; but to make assurance doubly sure, I kept blazing away in the direction in which I heard him plunging about. At length came a series of mighty groans, gradually subsiding into deep sighs, and finally ceasing altogether; and I felt convinced that one of the 'devils' who had so long harried us would trouble us no more."

In the wake of his heroism, Patterson went on to be a game warden in Kenya, and the book he wrote in 1907 about his time in Africa has become a classic of adventure writing.

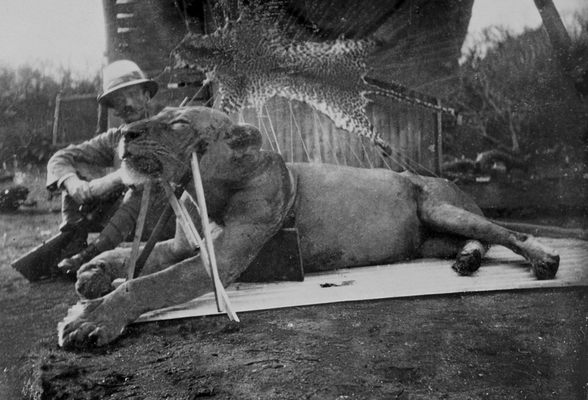

In 1924 Patterson visited the Chicago Field Museum to give a talk on his experiences with the man-eaters of Tsavo. After seeing the collections and receiving an enthusiastic welcome he offered the remains of the two lions, which had served as trophy rugs in his home for 25 years, to the museum for $5,000.

Thanks to the skills of taxidermist Julius Friesser the lions are exceptionally lifelike for mounts of their age, particularly considering their years as floor coverings. The resulting lions are somewhat smaller than the size reported by Patterson in his book, which may have to do both with exaggeration or mismeasuring on his part and some trimming of the skins required, both for creating tidy rugs and later for fitting over three-dimensional taxidermy forms. They are displayed next to their skulls, also preserved by Patterson. In a separate display, the Field Museum also houses the largest man-eating lion on record. Measuring 10 feet, six inches in length, the "Man Eater of Mfuwe" was responsible for the deaths of 6 people, and was shot in 1991 by a hunter.

Since the 1990s the Field Museum has been actively involved in further field research in the Tsavo National Parks. Researchers have studied the Tsavo maneless lions, and have located the man-eater's lair as shown in Patterson's book.

The story's fame was re-kindled by the 1996 film The Ghost and the Darkness, named for the two lions.

In surprise the railways are still in use today. under the control of the Kenya Railways Corporation. As their territory is encroached upon, the Tsavo lions continue to occasionally snack on humans.

Related Tags

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

July 1, 2012