About

On March 30, 1892, more than 1,000 people descended on Camden, New Jersey, a city of 60,000 on the Delaware River across from Philadelphia. They had arrived to pay their last respects to America’s greatest poet of the era, Walt Whitman. After years of declining health, Whitman passed away at his home on Mickle Street on March 26th at the age of 72. Crowds swarmed Whitman’s home for a chance to file into the parlor for a last look at Whitman in his oak coffin, though so many flowers and wreaths had been sent that the coffin was nearly subsumed by greenery.

At two o’clock, hundreds of the crowd followed the coffin in a spirited two-mile procession to Harleigh Cemetery. There, an eclectic and decidedly unconventional selection of readings were offered from the Koran and the Bible, as well as from works by Confucius, the Buddha, Plato, and Whitman’s own opus, Leaves of Grass.

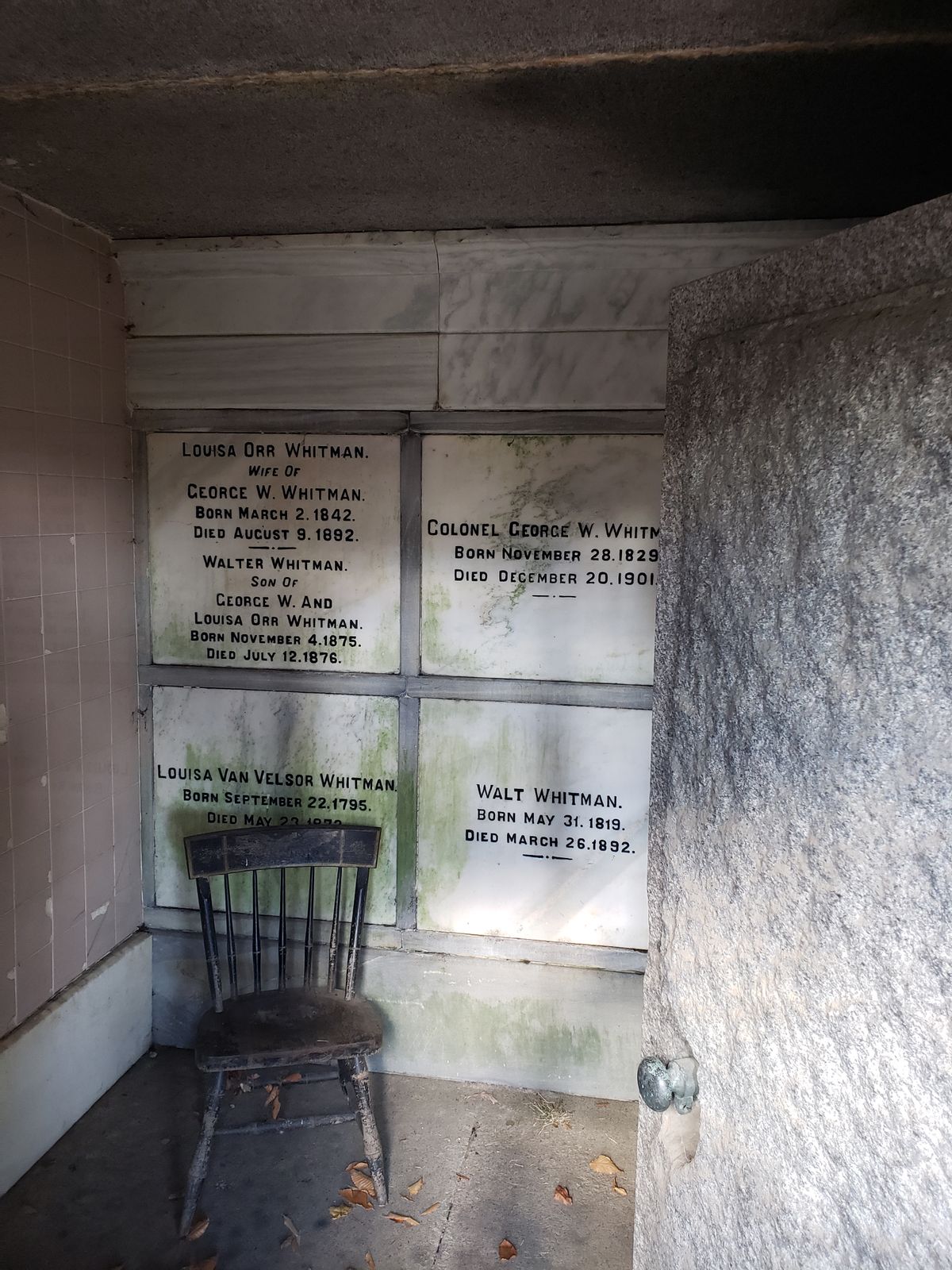

At the conclusion of the service, Whitman’s coffin was sealed into its final resting place in a grim and imposing gray granite mausoleum. The story of how this mausoleum was ready for this day is a tale of two years of active planning (and decades of mental preparation) by the poet himself.

Whitman arrived in Camden from Washington, D.C., in 1873 after suffering a stroke, moving in with his brother George Washington Whitman’s family. George’s household included his wife and children along with the brothers’ ill mother who was in the last few months of her life. George was a fairly prosperous and level-headed engineer, as grounded in the real world as his brother Walt was engrossed in metaphor.

In 1884, George moved to a new home for business reasons, and so Walt purchased a two-story row house on Mickle Street (now Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Blvd.) two blocks from George’s former home. It was in this house that Whitman would spend the rest of his life, frequently bedridden.

The small household included Mary Oakes Davis, a widow who served as his housekeeper in exchange for free rent, and another brother, Eddy, described as an “invalid” since birth. Mrs. Davis also managed a small personal menagerie which included a cat, a dog, two turtledoves, a canary, and likely much more. With a constant stream of friends and admirers, including Oscar Wilde and artist Thomas Eakins, the house was a cluttered and active place.

Despite the distractions, Whitman was intellectually active in the Mickle Street house, producing four separate edited versions of his poetic masterwork, Leaves of Grass, the last of which is commonly known as “The Deathbed Edition.” But there was no escaping his failing health. The house, with its peeling wallpaper and stacks of paper and dusty manuscripts on every floor and surface, mirrored his physical deterioration. His suffering worsening, Whitman’s thoughts turned still further towards preparations for his death.

As a volunteer nurse in the Civil War, Whitman observed the deaths of scores of soldiers, just as likely to be agonizing and slow as peaceful and quiet. His thoughts on death and eternity turned up frequently in his poems and letters. As he wrote in Leaves of Grass: "I bequeath myself to the dirt to grow from the grass I love, / If you want me again look for me under your boot-soles."

Now, though, the plans Whitman developed for his internment rejected a traditional in-ground burial. Instead, he designed a granite mausoleum, inspired by William Blake’s 1813 etching, “Death’s Door.”

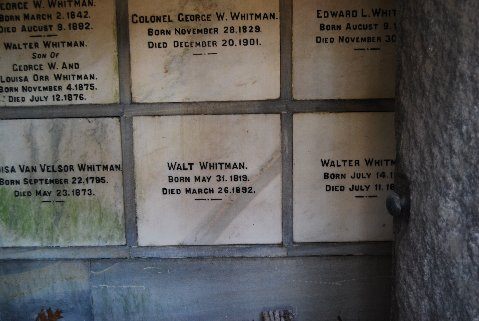

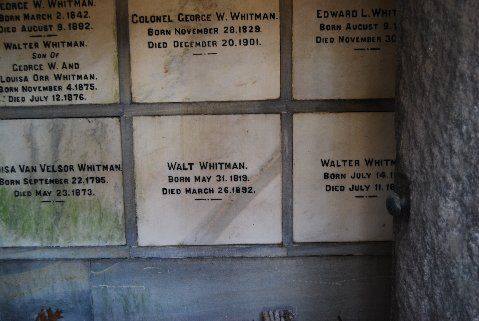

Nearby Harleigh Cemetery Association gifted Whitman a 20-foot by 30-foot plot on the edge of the cemetery where the tomb could be set into a hillside. In 1890 the poet commissioned a Philadelphia builder to construct the mausoleum for a whopping $4,000—twice the cost of his house on Mickle Street. Granite blocks from Quincy, Mass., some weighing eight to ten tons, were laid for two seven-foot high columns and a twelve-foot wide lintel framing a doorway. Whitman’s plan for a granite door was abandoned as being heavy to be practical, so an iron gate with a bronze lock was used instead, with a false granite slab installed to resemble a door left ajar. The walls were a foot-and-a-half thick, supporting a triangular pediment reaching 15 feet towards the sky. The interior was inlaid with white marble and red-brown tiles, and six bays in which Whitman intended to reunite his parents and four siblings after their deaths.

Whitman regularly visited the cemetery to review the progress being made on the structure. So pleased was he with how his vision was coming to life that he shared photographs with newspaper reporters, urging them to write stories about the project. This was a monument that the poet felt he deserved, not grandiose or especially elegant, but rugged and grounded, with rough-hewn stone rising from the earth. (Today, Whitman would not appreciate the landscape of his mausoleum—instead of the vine-covered leafy hillside he envisioned, the backdrop is a constant stream of diesel-belching trucks servicing a loading dock at the rear of the medical facility next door.)

In one last defining gesture, Whitman had the pediment inscribed with two words to last for eternity: WALT WHITMAN. While other family members might be interred within, visitors must never forget the name of the man himself.

In a somewhat macabre twist, however, the masons who chiseled Whitman’s name into the pediment also carved the date, “May 31, 1890” beneath it, somehow under the impression that the vault was a gift to Whitman from friends on the occasion of his 71st birthday. Whitman promptly ordered the date to be cut off, leaving the inscription on the pediment somewhat off-kilter in its raised position above the center line.

The builders completed their work in October 1891, but by then Whitman had become certain he was being swindled and thus balked at the final bill. Eventually, he paid $1,500, with the balance evidently being settled by one of his close friends and literary executors, Thomas Biggs Harned. This did little to assuage Whitman’s friends who had been not-so-privately complaining of the extravagant outlays for the mausoleum while Whitman was subsisting in near-penury and dependent on the generosity of his friends.

After Whitman’s death, his parents’ remains were moved to the tomb from graves in Brooklyn and Camden. In time the burial house would also come to hold the coffins of Whitman’s siblings Hannah, George, and Eddy, along with George’s wife Louisa and their infant son. By design, Whitman in his oak coffin resides in the center, with his family members above and beside him, reunited in eternity.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The GPS coordinates listed here lead to the cemetery's entrance. Go during the day, and be sure to check out the numerous other old family mausoleums throughout the cemetery!

Located at the intersection of Vesper Blvd. Just past the cemetery offices, stay to the left and follow the road a short distance down the hill to the grave site.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

June 12, 2019

Updated

August 10, 2023