About

In 1851, a group of fishermen from southern China shipwrecked on Whalers Cove, a rocky beach on California's Central Coast. They were some of the earliest Chinese people to set foot in the state. In Point Lobos, now a scenic coastal park just south of Monterey, they felt a spiritual connection to their home across the Pacific, and built a dozen cabins using pine and redwood lumber. They raised families there while fishing for shrimp and abalone.

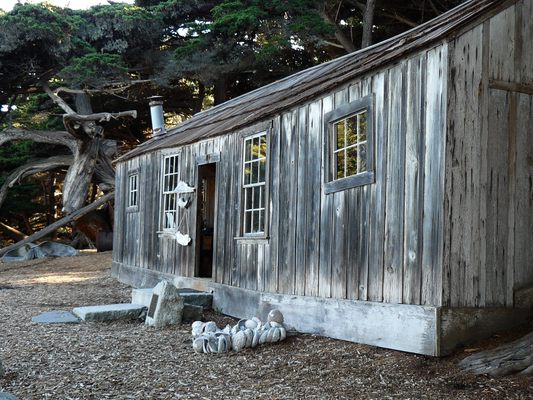

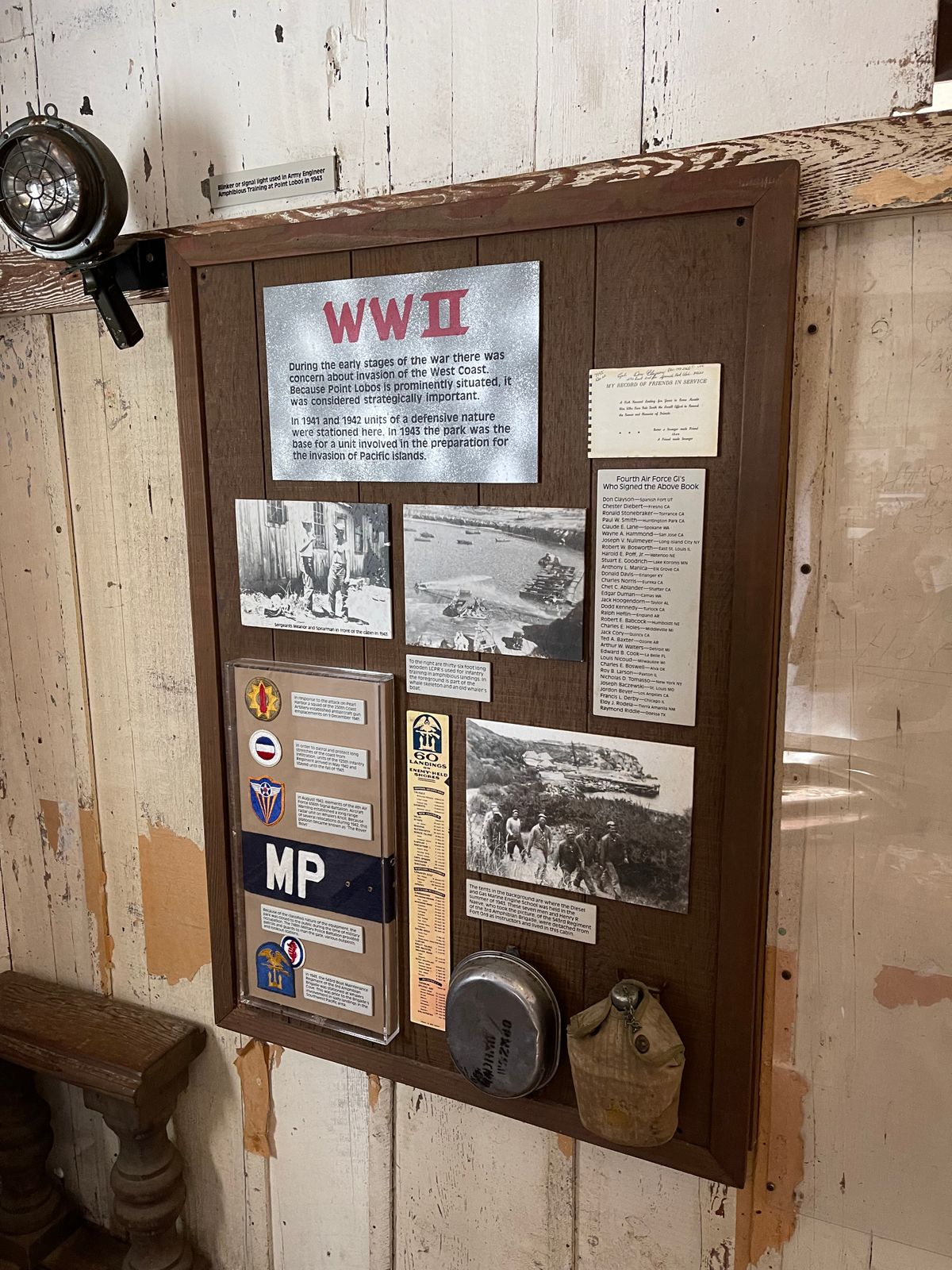

Today, only one building, the Whalers Cabin, remains. In 1994, it became a cultural history museum, replete with artifacts from the seafaring clans that inhabited Point Lobos through the turn of the 20th century: first the Chinese, then the Japanese and Portuguese. The multimedia collection spans nearly a hundred years of immigrant history. Vintage photographs of fishing crews adorn the walls. Shelves hold broken pieces of Chinese ceramics, fishing gear, and replicas of cottages. Abalone shells and whalebones lie outside the shack, around large pots used to cook blubber.

For a while, the region around Point Lobos, from Carmel River South to Big Sur, was a “wonderful place of tolerance and collaboration, where the Chinese, Portuguese, and Californians were all living shoulder to shoulder,” according to Sandy Lydon, a historian and author of Chinese Gold, an account of 19th century Chinese history in California. In 1859, eight years after the Chinese seamen arrived, their first descendant was born: a girl named Quock Mui. She learned to speak five languages and became the liaison between different ethnic groups, later adopting the nickname "Spanish Mary." A photograph of her in old age hangs in the cabin.

The peace lasted until 1879, when rampant anti-Chinese sentiment—and the arrival of a new property owner—swept families like the Quocks out of Point Lobos. Most resettled a few miles north to Pebble Beach and Pacific Grove, and went on to transform the Monterey Peninsula into a commercial fishing empire. But the discrimination, from competitors and elected officials, continued there. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, a ban on Chinese fishing methods, and a village fire of suspicious origins eventually wiped out the Chinese enterprise by the early 1900s.

It took many decades for the state of California to recognize the immense contributions made by its Chinese immigrants. Today, a wealth of literature commemorates the railroad builders and gold miners who had long been written out of history. But the fishermen who toiled alongside them and established the state’s first commercial fisheries remain obscure. Whalers Cabin is one of the few exhibits dedicated to their memory.

Related Tags

Know Before You Go

The Point Lobos State Natural Reserve charges an entrance fee of $10 per vehicle. It opens at 8:30 a.m. and closes at 5 p.m. The best time to go is the summer, as the cabin is often closed during winter months. Wear hiking shoes to check out the beautiful coastal trails along the coves. Dogs are not allowed in the park, and neither are drones.

Community Contributors

Added By

Published

March 6, 2020