Coltsville, USA: Inside America’s Gun-Funded Utopia

Coltsville (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Just off Interstate 91 near Hartford, Connecticut is an architectural oddity that would look more at home in Moscow’s Red Square than alongside a placid section of the Connecticut River. Visible from the road is a giant dome in the shape of an onion, colored bright blue, emblazoned with gold stars, and topped with a statue of a rampant horse.

Underneath that blue dome lies the abandoned ruins of a factory once owned by a man who changed American history, the innovator of the revolver, Samuel Colt. Sprawling around the crumbling red brickwork of the old Colt’s Patent Fire-Arms Manufacturing Company, once the largest private armory in the world, are the remnants of Coltsville, the utopian village he built for his workers.

A model of 19th century industrial paternalism, Coltsville included a church, a social hall for dances and lectures, workers’ housing, a giant landscaped park home to deer and peacocks, sculpted botanical gardens, and thousands of feet of greenhouses filled with tropical fruit and flowers. Samuel Colt felt such responsibility for the welfare of his workers outside the factory that he went so far as to build a tiny German village for his skilled craftsmen from Germany, complete with a beer hall and ski chalets.

Remarkably, most of the idealistic village created 150 years ago is still intact, although it has not been preserved in any way, and is little known outside of Hartford.

Samuel Colt’s brief but brilliant career, which ended when he died in 1862 at the age of 47, is principally known for developing the first practical revolver. While sailing on the brig Corvo, bound for Calcutta, 16-year-old Samuel Colt was struck by the rotating locking mechanism of the ship’s capstan. Inspired to apply the principal to pistols, he carved a wooden model of a firearm with a revolving cylinder. Prior to the revolver, the flintlock pistols and muskets popular at the time were time-consuming to load and dangerous to handle. Colt’s invention meant you could rapidly fire six shots without reloading.

Such was the demand for Colt’s revolvers that he built a giant manufacturing plant in his hometown of Hartford,. Selecting 250 acres south of the city that were prone to flooding from the bordering Connecticut River, Colt devised a dyke to protect the estate and persuaded the New York, New Haven and Hartford railway to construct a branch line running alongside the factory.

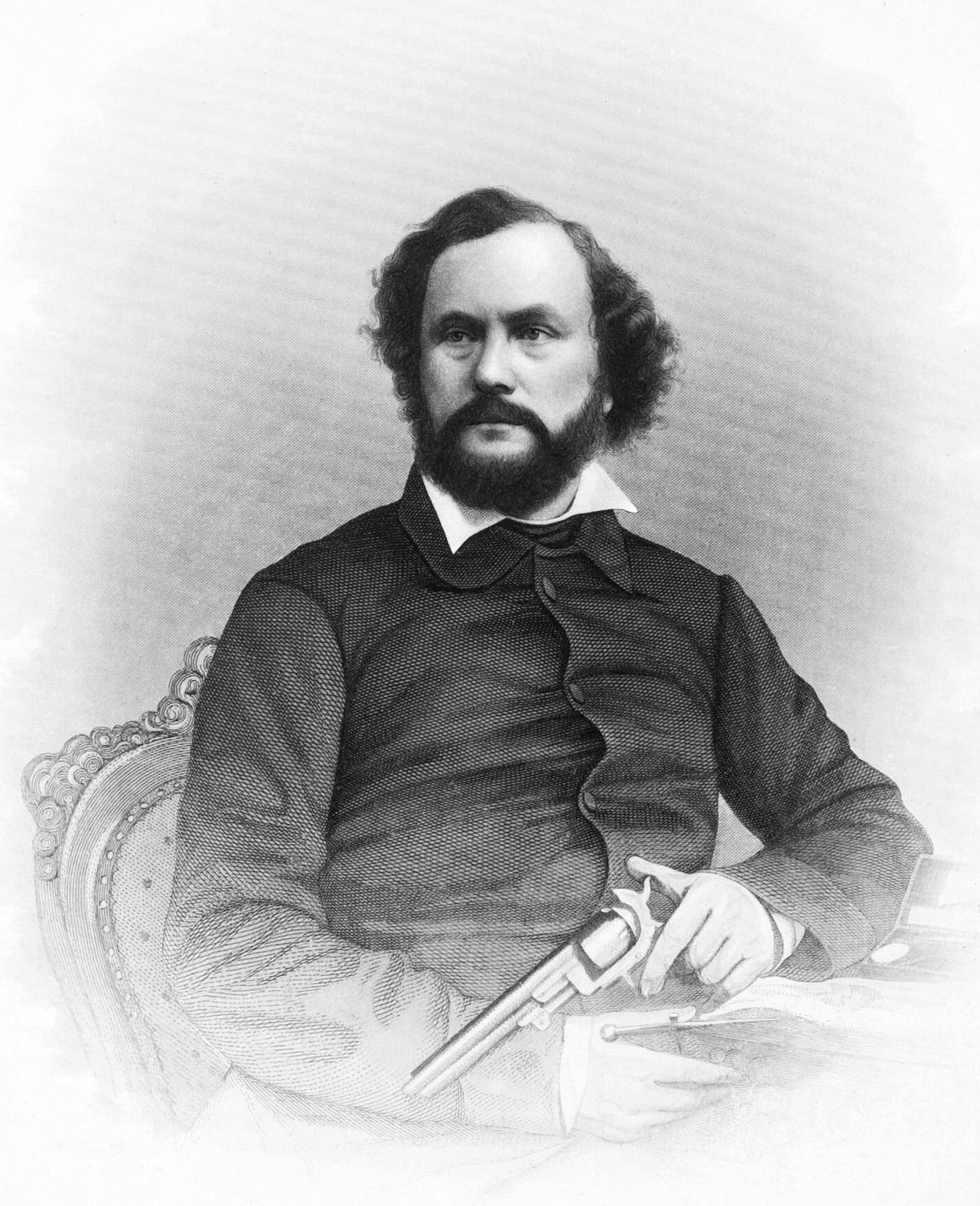

Engraving of Samuel Colt with the 1851 Navy Revolver by John Chester Buttre, c.1855 (Photo: Public Domain)

Engraving of Samuel Colt with the 1851 Navy Revolver by John Chester Buttre, c.1855 (Photo: Public Domain)

Colt’s Manufacturing Company abandoned the property in 1994, moving west of the city. The railway line is still there, rusted and unused. Before the construction of Interstate-91, the red brick facade of the main entrance looked directly onto the river.

The giant blue dome that looks wildly out of place in Connecticut was actually inspired by the Orthodox churches in St. Petersburg, Russia, where Colt presented Czar Nicholas I with a gold, engraved Dragoon revolver. This cobalt symbol of Colt’s flamboyance sat atop the east armory, which was similarly ornate and remarkable for a 19th-century factory, designed in the style of the Italian Renaissance. The original sign that hung above the main entrance is still there, decorated with an oversized Colt revolver.

As innovative as Colt’s revolver was, his manufacturing plant was even more so. He advanced the concept of interchangeable parts, and introduced the concept of production lines six decades before Henry Ford. At the plant in Hartford, 80% of the work was done by steam driven machines.

Colt himself designed the factory with his architect nephew H.S.Pomeroy, and the company president Elisha K. Root. It was laid out in an H-shaped pattern where parts were produced in the wings and fed into the central assembly line. Today about half of the plant is gone, including the old central assembly line. South of the east armory, past the ruins of the iron foundry and the finishing shop, are the remnants of the old forge and blacksmith’s shop. In its heyday, the Colt factory was turning out over 150 guns a day.

The ruins of the iron foundry. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The ruins of the iron foundry. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Hartford’s most famous resident, Mark Twain, visited the plant in 1868, describing a “dense wilderness of strange iron machines, a tangled forest of pulleys, wheels and all the imaginable and unimaginable forms of mechanism. It must have required more brains to invent all those things than would serve to stock 50 senates like ours.”

Where once the factory would have reverberated with the unrelenting pounding of drop hammers and production lines, powered by the enormous steam engine located in the rafters, today there is only silence.

The company’s first sales triumph occurred when Captain Samuel Walker ordered 1,000 revolvers for his Texas Rangers. He improved the revolver design with the 1851 Navy model, but it was the Colt Single Action Army model that has gone down in history as the “gun which won the west.” Also known as the Colt .45, or the Peacemaker, it was the workingman’s gun of the frontier and played a vital role in the westward expansion of the United States.

Colt’s advertising ran that “Abe Lincoln may have freed all men, but Sam Colt made them equal.” The guns carried by Wyatt Earp, Jesse James, Wild Bill Hickcock and Doc Holliday sprang from the now-crumbling buildings and silent smokestacks of Coltsville. When Theodore Roosevelt’s Rough Riders charged up the hill at San Juan, they did so brandishing Colt .45s.

But Colt’s success with the revolver is really only half the story. Together with his wife Elizabeth Jarvis Colt, he created an entire thriving village intended to promote the welfare of the workers. Across from the street from the remains of the armory, running along Huyshore Avenue, were the workers’ homes. Originally there were 50 brick buildings, each capable of housing six families, but today only 10 remain.

Women inspecting Colt .45 parts, at Colt’s Patent Fire Arms Plant in Hartford. (Photo: Library of Congress)

The newer white paint is fading to reveal the original red brick underneath, and the wooden balconies are somewhat dilapidated. But the buildings are still occupied, and now serve as low-income housing. Bushes growing over the gateway obscure an old sign for Colt Estates.

Walking further down Van Block Avenue, past an industrial wasteland to Curcombe Street, is a peculiar collection of cottages that would look more at home in the Swiss Alps. These are the remnants of what was once a flourishing sub-community within Coltsville. To persuade skilled workers to emigrate from the German-speaking lands, Colt built a replica Alpine village complete with Swiss chalets, and named it Potsdam, after the Prussian royal city outside of Berlin.

His remarkable attention to detail saw the cottages designed with low-pitched roofs, and elaborate overhanging eaves with diamond-shaped wooden balconies. He even built a traditional beer hall, or Bierpalast, called Germania. In the age of industrial giants and robber barons, such benevolence was extraordinary, a far cry from the factory conditions that led to such disasters as the Triangle Shirt Waist factory fire in New York.

The Colt 1851 Navy, the favored gun of Doc Holliday, from the Museum of Connecticut History (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The Colt 1851 Navy, the favored gun of Doc Holliday, from the Museum of Connecticut History (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Not that Colt wasn’t a ruthless businessman. He unrelentingly pursued patents for his revolvers, suing competitors until he monopolized the industry. He was equally firm with his employees: a sign on the factory floor stated “everyman employed in my armory is expected to work 10 hours during the running of the engine and no one who does not cheerfully consent to do this need expect to be employed by me.”

Yet at the same time he introduced mandatory one-hour lunches. Along with Elizabeth, he built a church, a concert and dance hall that could seat 1,000 residents, and a newspaper reading room. He encouraged social clubs for the new craze of bicycling. The Colt Brass Band was dressed in dazzling uniforms of Prussian blue.

When Samuel and Elizabeth got married in Coltville, the Hartford Courant wrote a dispatch from the reception:

“The steamboat Washington Irving started from the wharf at the foot of Van Dyke Avenue in front of the armory at 12 o’clock. The steamer was gaily decorated with flags, and as she swung out into the stream a grand salute of rifles was fired from the cupola of the armory by a company of the workmen.”

Surrounding the armory and workers’ housing was a giant park. Home to wild deer, livestock, peacocks and orchards, it resembled an English country estate. The sculpted lawns, botanical gardens and lakes provided greenery for his worker’s leisure hours. The jewel of the estate is still there, a pink-hued mansion the Colts called Armsmear.

Armsmear mansion. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Armsmear mansion. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Armsmear was an ornate home set high on the hill overlooking the grounds running down to the factory. Designed in the style of a luxurious Italian villa, with towers and domes, it was surrounded by large reflecting pools decorated with fountains. Alongside Armsmear was a greenhouse where fruits and flowers from all over the world—like pineapples, figs, and grapes—grew.

When Elizabeth’s father saw it, he was astounded: “Such profusion of rare flowers I have seldom seen … the most singular sight was that of cucumbers hanging down from the vines which were trained up to the roof by hundreds.” Elizabeth described the home as “suggesting at once elegance and refinement” with “large halls for state occasions and crowds, as well as cozy cabinets and boudoirs for household comfort and genuine sociability.”

But the Colts married life was short and filled with tragedy. When Elizabeth was 35 and had been married to Samuel for just over five years, he died suddenly at the age of 47. Of their four children, three died in childbirth or shortly thereafter. The sole survivor, Caldwell Colt, drowned at sea during a sailing trip off the coast of Florida.

When Samuel Colt succumbed to gout in 1862, Elizabeth inherited a controlling interest in a company valued at an estimated $15 million dollars (approximately $341 million in today’s money). At the time, Colt firearms were producing an estimated 1/996th of the entire gross national product of the United States. Despite living in an age where she couldn’t vote, Elizabeth steered the company until 1901 (with her brother Richard Jarvis as president), becoming one of the most prominent female industrialists in America.

The Memorial Church of the Good Shepherd. (Photo: Library of Congress)

The Memorial Church of the Good Shepherd. (Photo: Library of Congress)

She continued to develop Coltsville, building a beautiful new Gothic church, the Memorial Church of the Good Shepherd, as a tribute to her late husband and children. Located adjacent to the armory, the church features an exquisite stained glass portrait of Samuel Colt, and still serves as a bustling community church in Hartford. Across the street from the Good Shepherd Church, Elizabeth built a parish hall in honor of Caldwell to be used for local events. Decorated with ship motifs, with interiors resembling the bows of a ship, today the hall is used as a venue for the parishioner’s social activities.

With no remaining children, Elizabeth willed her extensive collection of rare art to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, one of the oldest art galleries in America. The Elizabeth Hart Jarvis Colt Memorial Wing was the first American museum wing to bear the name of a female patron.

As for her elaborate palazzo mansion, Armsmear, she simply gave it away. In the terms of her will, it was to become a retirement home for widows, which is what it is today. Walking through the neatly tended gardens, in the shade of the towers of the stately home, I spoke with a woman named Fay who lives in Elizabeth’s grand personal chambers.

Charles Loring Elliott’s 1865 painting of Elizabeth Colt and son. (Photo: Courtesy Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art)

Elizabeth also gave away more than 200 acres of landscaped grounds, this time to the city for use as a public park. Although peacocks and wild deer no longer frolic here, Colt Park is a popular picnic spot, home to baseball fields and sweeping views.

At the top of the hill is a statue of Samuel Colt, a frieze commemorating the day he presented a Colt Dragoon model to the Czar of Russia, and a statue of a worker polishing the distinctive cylinder chamber that made Colt his fortune. The memorial reads: “on the grounds which his taste beautified, by the home he loved, this memorial stands to speak of his genius, his enterprise and his success, and of his great and loyal heart.”

Today the condition of Coltsville is somewhere between Chicago’s celebrated Pullman Historic District, the first model industrial community in America, and Henry Ford’s abandoned rubber plantation utopia, Fordlândia, which is decaying in the Brazilian jungle. Whilst Pullman’s village was effortlessly designated a National Park, Coltsville faced years of struggle to receive similar landmark status, due almost entirely to what was produced there.

Guns have long been a divisive subject. Plans to turn the industrial community into a National Park have been championed since the Colt company vacated the premises in 1994, without success, and the plant was allowed to fall into ruin.

The cobalt dome. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

While Hartford’s other famous resident, Mark Twain, is easy to promote as a tourist attraction –the home where he wrote many of his most famous works was designed by the same architect as Armsmear—a sprawling, mostly derelict, 19th-century factory centered around the manufacture of arms and ammunition was a much harder sell, especially after the tragic Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting in Connecticut in 2012.

However, after nearly two decades, Coltsville finally received congressional approval to become a national park in December 2014. The plans call for “a Coltsville National Historical Park dedicated to the accomplishments of Samuel Colt and the role that his firearms and factory played in the Industrial Revolution.”

Parts of the old east armory are already being renovated for what will be a 10,000-square-foot museum and visitor center. Other sections of the plant will be made into apartments, offices and schools, with apartments already rented in part of the old south armory, alongside a school for art and design.

Yet the future of Coltsville remains uncertain. The old finishing shop, blacksmith’s, and foundry remain in an advanced state of dilapidation. The workers’ housing is suffering from years of neglect. Large tracts of industrial wasteland lead the way to the rundown remnants of the Alpine chalets of the German-themed section, Potsdam. But the historic park, church, memorial hall, and Armsmear itself are still focal points in the community created by Samuel and Elizabeth Colt over 150 years ago.

Samuel Colt’s memorial site, Cedar Hill Cemetery. (Photo: That Hartford Guy/Flickr)

Samuel Colt’s memorial site, Cedar Hill Cemetery. (Photo: That Hartford Guy/Flickr)

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook