A Forgotten Botanist’s Stunning 19th-Century Manuscript Is Now Online

It is considered one of the most comprehensive works on Cuba’s flora during the colonial period.

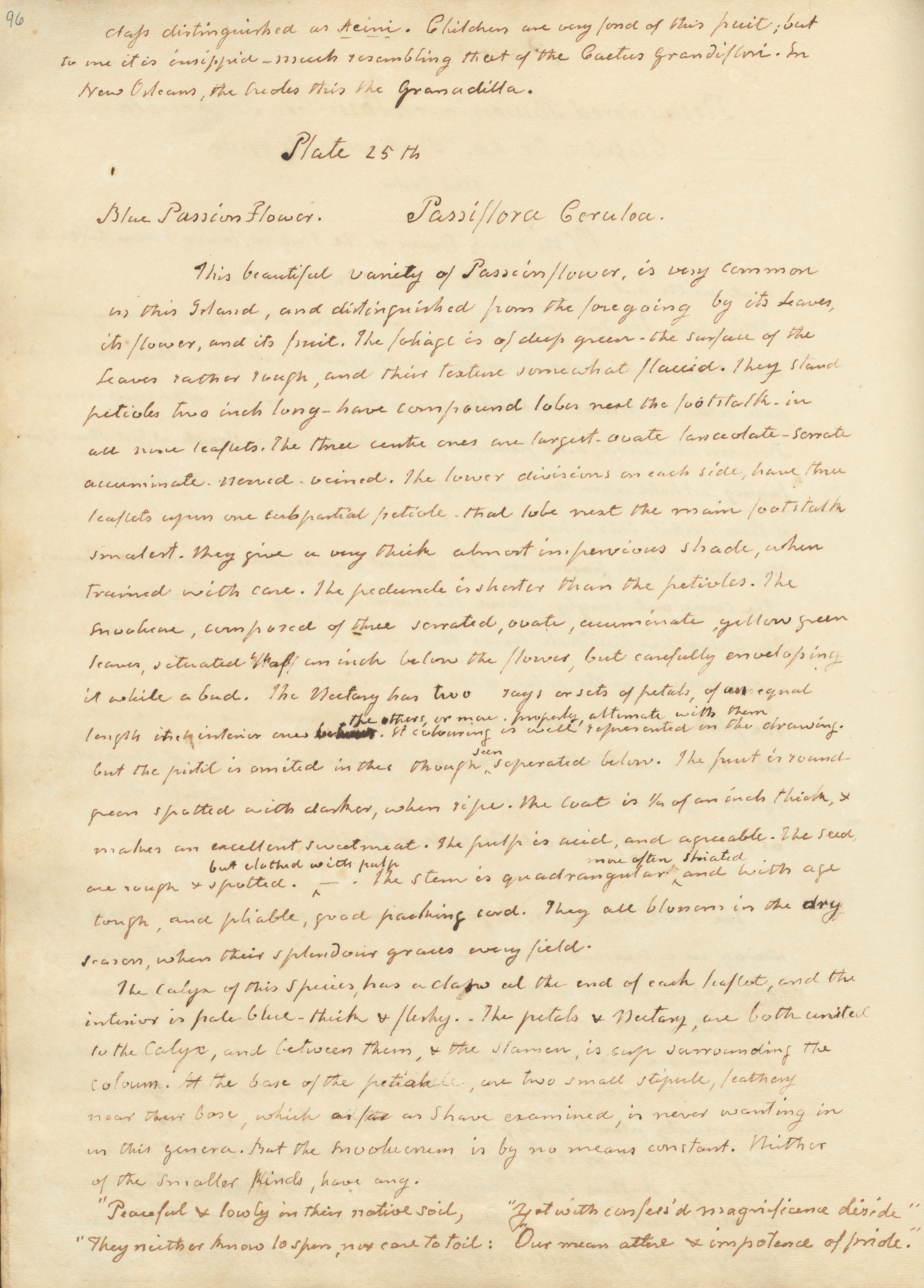

After the death of her husband Charles in 1817, an American woman named Nancy Anne Kingsbury Wollstonecraft moved to the Cuban province of Matanzas and began studying the island’s plant life. In the mid-1820s, she compiled that research into a stunning and extensive manuscript entitled Specimens of the Plants and Fruits of the Island of Cuba. Nearly two centuries after her own death in 1828, her work has been digitized and made available for download at the HathiTrust digital library, by way of Cornell University’s Library Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections.

Specimens of the Plants and Fruits of the Island of Cuba is considered one of the most comprehensive works on Cuba’s plant life during the colonial period. “Its significance lies in the fact that it appears to be one of the earliest known botanical documents containing illustrations of Cuban flora,” writes Anne Sauer, the Stephen E. and Evalyn Milman Director of the RMC, in an email. “That it was also made by a relatively unknown, but clearly well-educated and dedicated female amateur botanist, is also extremely important.”

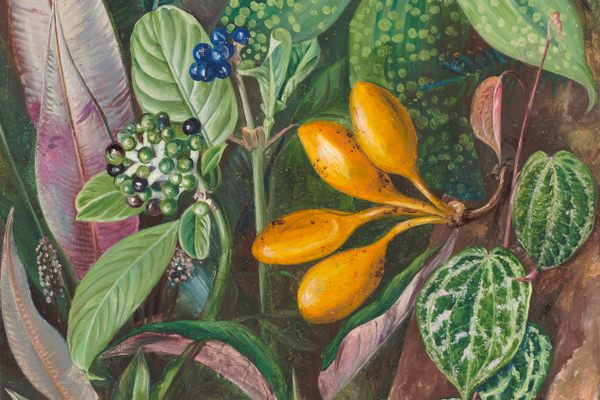

The watercolor illustrations of plants were all done by Wollstonecraft and include an analysis of the plant and its biology. According to the Cuban historian and author Emilio Cueto, who gave a presentation on the manuscript in November 2018, only 145 illustrations had been done of plants in Cuba at this point in history. Wollstonecraft was responsible for at least 124.

Unfortunately, Wollstonecraft died just months after sending her manuscript to publishers in New York. However, she did see some of her other writings make it to print.

Under the pseudonym D’Anville, she published two letters detailing her exploration of Cuba’s ecology. In one correspondence entitled Letters from Cuba No. II, published in the spring of 1826 in Boston Monthly Magazine, she describes the array of stalactites hanging in the caves she visited, along with the “fine, full, deep, green foliage” that made up the countryside.

Wollstonecraft, who was Mary Wollstonecraft’s sister-in-law and Mary Shelley’s aunt, wasn’t just a champion of natural history, but also fought for the betterment of women’s rights.

Using the same pseudonym, Wollstonecraft wrote The Natural Rights of Women, published a year before her letters in the same magazine. She calls for improvements to the American educational system and stresses that more opportunities need to be created for young girls to study literature and sciences:

“Ladies are no longer afraid, nor ashamed to be acquainted with history, with geography, with natural history, or with whatever has a tendency to enlarge their views, strengthen their understanding, improve their taste, or amend their heart.”

Around 220 pages of text along with 121 watercolor images can be viewed through the digital library. The manuscript appears to be missing 24 visuals, though it is unclear whether they have been lost, or were simply never created by Wollstonecraft in the first place.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook