In London, Natural History Museums Confront Their Colonial Histories

It’s not as easy as returning stolen statues.

The shipworm is an unassuming creature—not a worm, actually, but a bivalve mollusk with a soft, naked body that coils out of a smaller shell like a beckoning finger. In the Grant Museum of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy at University College London, the diminutive specimen is preserved and placed alongside pieces of a ship it had begun to devour, its skinny white body juxtaposed against fissured brown wood.

Natural history museums have all sorts of things in their collections, but even so, it might seem an odd choice to put this mollusk on such prominent display. But the shipworm was a creature of great interest to colonial Britain. The worm gets its name from its preferred diet, and they bored deep into wooden hulls, imperiling their structural integrity and, in turn, the entire empire. Though shipworms are spread across the globe, they swarmed in massive abundance in tropical waters along the coast of Africa and the Caribbean, posing a particular threat to traders who sailed there. No one knows precisely when this particular individual was collected, but it came to the Grant Museum’s collections sometime in the late 19th century from Bristol, one of the main shipping ports of the British Empire—and a major site of the transatlantic slave trade (when that was still practiced some decades earlier). The shipworm’s connection with empire and conquest is why it’s on display today.

There’s nothing in the museum’s records about the ship the bivalve came from or specifically when it had been collected, but, in a way, the sample is still associated with the business of moving millions of enslaved Africans to colonial holdings around the world. “It’s not a smoking gun,”says Subhadra Das, a science curator at the Grant Museum. “[There’s] nothing in the catalogue saying that the wood it came from belonged to a slave ship.” But in her eyes, it had been collected, studied, and preserved because of its impact on the British colonial economy—making the specimen itself part of it.

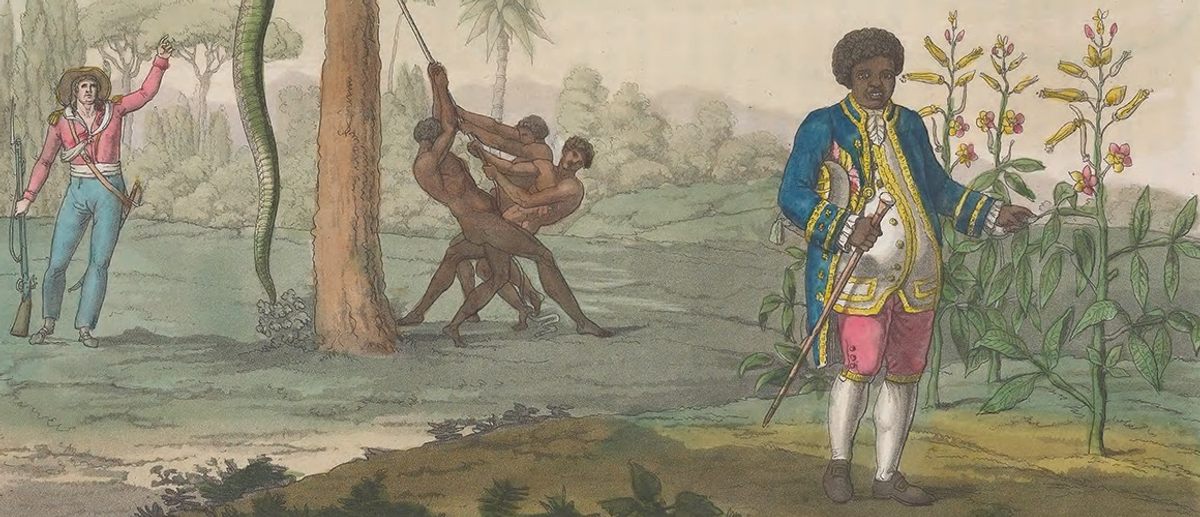

The history of natural science as we know it today is inseparable from the history of European colonialism. Both art and natural history museums have long showcased objects collected—some would say “stolen”—from faraway lands and cultures. The purpose of these institutions is educational, and they were also about glorifying the colonial empires that created them, according to a 2018 paper written by Das and Miranda Lowe, the principal curator of crustaceans at London’s Natural History Museum, and published in the Journal of Natural Science Collections. “Empire isn’t just putting down a flag and shooting people,” Das says. “The way you teach science is one way of creating an empire.”

Western art museums have begun to confront this history with what is called “decolonization,” or the process of removing or contextualizing racist depictions and, where possible and practical, repatriating artifacts. These issues become trickier when one swaps the Parthenon Marbles (acquired in Greece and on display in London) for, say, the skeleton of an extinct thylacine, collected in Tasmania. “When you talk about decolonization, you think of questions of repatriation and restitution, giving an artifact back to a former country and focusing on ethnographic and archaeological collections,” says Alistair Brown, policy manager at the Museum Association. “What Miranda and Subhadra are doing is taking some of the ideas developed around that work and turning that lens on natural history collections.”

In London, Das and Lowe, from two different natural history museums, have taken steps toward addressing the history of empire and colonialism in their collections by uncovering the hidden contributions of people of color, as well as the cultural context in which specimens were often collected. Conversations around decolonizing natural history museums have been going on for years—the Technical University of Berlin held a two-day workshop in 2018 devoted to the subject. And recently, the American Museum of Natural History in New York opened an exhibition to deal with criticisms around its prominent statue of Theodore Roosevelt in which the former president rides a horse—flanked by a subordinate Native American man and African man. But detailed scrutiny of these collections is not widespread, in part because it raises uncomfortable questions and in part because it is difficult.

“It would be very easy to talk about overt racism,” Das says. “But what we’re talking about is something different, which is that these stories have been left out.” Das and Lowe’s changes are small, slow, and at times imperfect, but they represent some of the first institutional steps toward reckoning with decolonization in science and natural history museums.

Natural history museums have their roots in the Enlightenment, when Europe pivoted from religion to science as a way to explain the world. They also descend from curiosity cabinets and ethnographic collections, such as that of 17th-century Danish physician Ole Worm, who helped put non-Western civilizations on the same level as natural oddities.

Racism was baked into many of the early scientific ways of looking at humanity. Taxonomist Carl Linnaeus himself described black people as “crafty, indolent, negligent” and European people as “governed by laws” in A General System of Nature in 1806. Museums, in turn, held the skulls of non-white humans as a way to establish the superiority of Caucasians, Das and Lowe write. In London, these skulls came from all over the empire. In the United States, Native American remains were commonly put on display.

The core collection of London’s Natural History Museum came from Sir Hans Sloane. As a young plantation doctor in Jamaica in the late 17th century, Sloane amassed more than 800 plant specimens—collected by the enslaved Ghanaian people on the plantation. Sloane later returned to London, married the widow of a plantation owner and, with his newfound wealth, dispatched surgeons on slave ships to collect more specimens. “Hans Sloane was a great scientist but the collections that he made didn’t exist in a happy world in isolation to what else was going on,” Lowe says.

In 1753, Sloane’s collection—which had grown to more than 71,000 plants, animals, gemstones, coins, and antiquities, from West Africa, South Asia, North America, and the Caribbean—was purchased by the British Museum, according to the Natural History Museum’s 2018 report on its historical connection to the slave trade. It’s notable that the Sloane collection, and that of the modern museum in general, maps neatly onto the parts of the world the British colonized, with many specimens from India but precious few from China, Das says.

In 2018, a survey of lower-income people of color in London found that they often felt excluded by science museums. People from Somalia and Sierra Leone, for example, took issue with the depiction of Africa as a continent burdened by disease and “saved” by the West. Another, from Latin America, was disappointed that an exhibit of Colombian butterflies failed to mention any actual Colombians.

As people of color in predominantly white institutions, Das and Lowe have been thinking about issues of erasure and exclusion for their entire careers. Both are founding members of Museum Detox, a network for museum workers of color founded by Sara Wajid, who is now at the Museum of London. Like many British ideas, Museum Detox started in a pub, in 2014. “It’s like the Sex Pistols. Everyone says they were there that day,” Das says. “But Miranda and I definitely were.” Das, Lowe, and others had grown tired of seeing the museums they work for pay lip service to diversity and inclusion without looking inward, at their own histories, policies, and approaches to science communication. Museum Detox has since grown into a robust collective that advocates for diversity in museums, both in the people they hire and the collections they show.

In 2016, Das and Lowe saw a tweet from Danny Birchall, the digital manager at the Wellcome Collection. “Natural history museums are more racist than anyone will admit,” Birchall wrote. “Obviously natural history museums are more racist than anyone is willing to say,” Das says. “But how do we go about proving that?” After a couple of years of thought and research, in 2018, the duo presented a paper exposing the Natural History Museum’s colonialist history at a natural sciences conference in Leeds. “Everyone was so open and welcoming,” Das says. “But the consensus was ‘Oh, we’d never thought about that before.’”

In London’s Natural History Museum, Hintze Hall holds a veritable forest, if you look up. The soaring, vaulted ceiling is comprised of 162 gilt-edged panels illustrating plants of the world. Some are native to the United Kingdom, such as the English oak. A full 108 of them depict plants from English colonies or considered significant to the empire. Cotton, tea, and tobacco are among the delicate paintings. (The English oak, it’s worth noting, was used for the ships that gave the empire its global reach.)

One of the panels depicts Quassia amara, also known as the bitter-ash. Linnaeus named Quassia after Graman Kwasi, a Ghanaian healer and botanist, according to the museum’s slavery report. Kwasi was enslaved as a child and taken to Suriname, then a Dutch colony. Around 1730, Kwasi had discovered the bitter-ash’s power to treat infection by internal parasites. He later sold the plant and the treatment recipe to a Swedish soldier, who took it straight to Linnaeus.

Lowe knew of Kwasi long before she started working at the Natural History Museum. His was one of the only stories she encountered in the field about a person of color, but was rarely mentioned as anything more than a footnote. Lowe’s father is from Barbados, the former British colony that provided the blueprint for all its subsequent slave colonies. “Growing up, I would hear all these stories about the Caribbean,” she says. “That’s why Kwasi resonated with me really deeply as a person of color.”

Kwasi’s legacy is complicated, as he helped the Dutch capture African people who escaped from slavery, but his is one of the few names known among the countless enslaved people who contributed to specimen collecting over the years (in part due to his relationships with white people). To Lowe, Kwasi exemplifies the hidden history of indigenous and African people who contributed to the museum’s collections, with little or no recognition.

Now Lowe tells Kwasi’s story in a tour she developed to highlight black history in the museum. On the first one—in October 2018, Black History Month in the United Kingdom—18 people showed up. “You’re really here for the tour? Do you know we’re making history?” Lowe remembers asking. “No one knew what they were going to get.” After leading them to a bust of Charles Darwin, Lowe told them the story of John Edmonstone, the formerly enslaved man who taught the biologist taxidermy.

Lowe, who has worked at the museum for 28 years, had been thinking about giving a tour like this for over a decade. As the principal curator of crustaceans, she is paid in part to care for 185 treasured Blaschka models, glass depictions of marine animals. Kwasi and Edmonstone do not technically fall under her purview, but she’s researched these stories and others on her own time, after hours. “It’s just something I do after five ’o clock, when the building is quiet,” she says. “It’s all about how hard you push within an institution where you work, especially if you’re one of very few people of color in an institution.”

Now, after the paper and in response to decolonization discussions, the museum has offered to train people to deliver Lowe’s black history tours—so she can spend more time making the museum more accessible and spreading awareness of its resources to marginalized communities. This outreach, again, is something Lowe has done for years on evenings and weekends.

Lowe sees her work as progress toward a goal that is, at its heart, unachievable. “I don’t believe you can fully decolonize a museum,” she says, noting that the Natural History Museum was built with the profits of empire, including those produced from the slave trade and other exploitative practices. In her eyes, you’d need to tear the entire thing down and rebuild it with ethical labor.

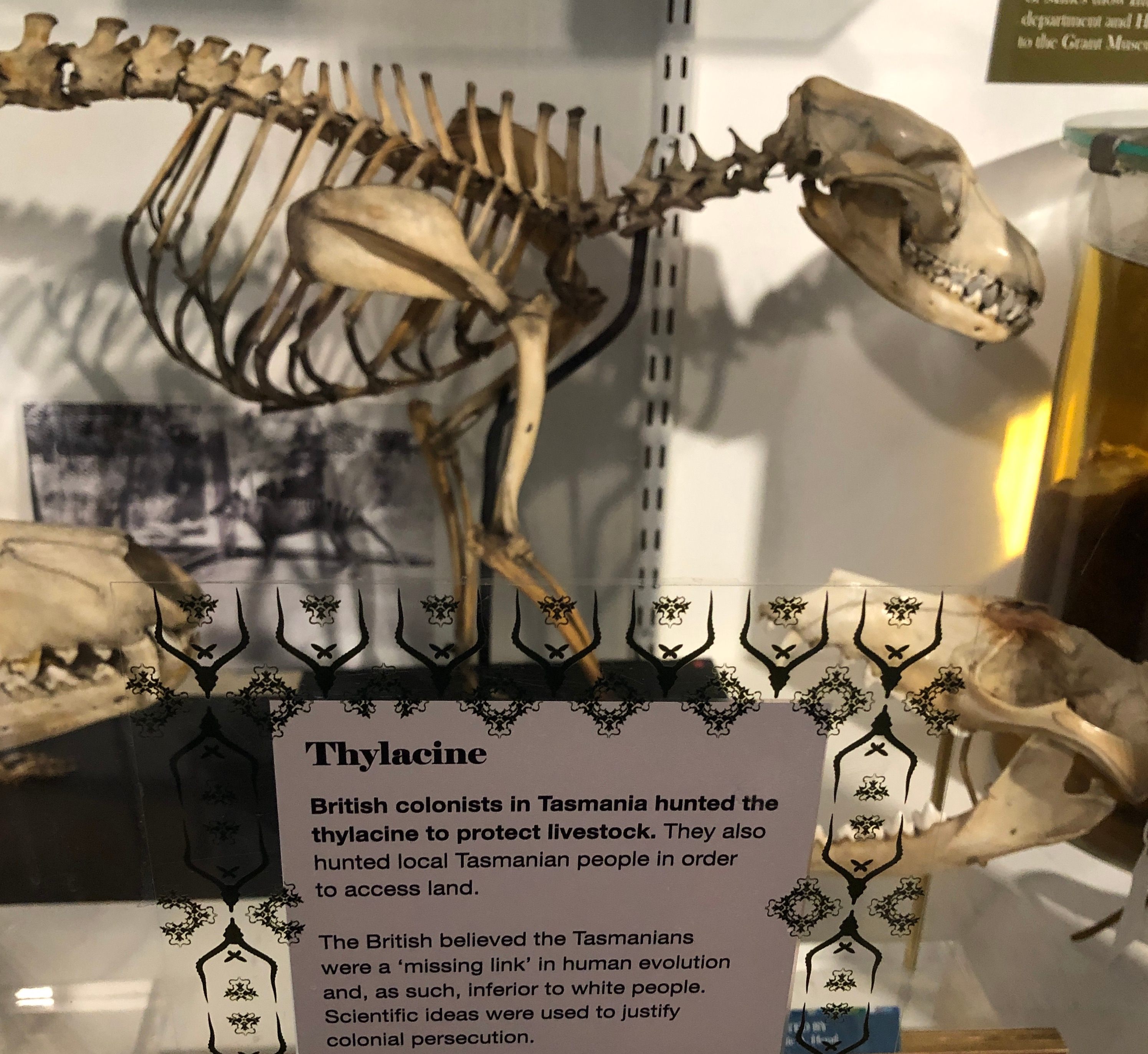

The Grant Museum, the last university zoological museum in London, is decidedly old-school, with shelves crammed full of animals in jars and display cases. “It’s a really beautiful dead Noah’s Ark,” Das says. Many of the specimens seem remarkably ordinary, such as a fastidiously documented collection of termites, but others stand out, such as the thylacine skeleton, the box of dodo bones, or even the jar of 18 moles.

Smaller, more obscure institutions such as the Grant Museum, Das says, have a better shot at enacting demonstrable change than large, entrenched ones such as London’s Natural History Museum. The entire Grant Museum is confined to a single room, with just 68,000 specimens in its archives (compared with approximately 80 million for its larger sibling). “A small team can be creative in ways that larger institutions might not have the freedom to,” says Tannis Davidson, the curator of the museum.

On September 19, 2019, Das and Davidson opened the temporary exhibit called Displays of Power, which presents the museum’s collection alongside information that acknowledges how it is tied to empire. The show, also co-curated by UCL curators Luanne Meehitiya and Hannah Cornish and designed by Darren Stevens, leaves the specimens where they are but adds labels to the glass that explain where the animal came from, who brought it here, and why it was collected it in the first place.

The Grant Museum has around 9,000 of its 68,000 specimens on display at any given time, and 31 got these new labels for the exhibition. “Any one of these could have that kind of story,” Davidson says. The label beside a trophy skull of an impala shot in Kenya in the 1960s reads: “Game hunting was encouraged by the British Empire as a way to push the colonial frontier further into Africa.” The label overlaying the shipworm reads, “Studying marine life that could damage ships—like shipworm—was important scientific work for keeping the Empire afloat.”

The star of the Grant Museum is that thylacine, or Tasmanian tiger. The striped carnivorous marsupial became a poster child for extinction after it was hunted into oblivion by British colonists in the early 20th century. This, to many, is not a new or surprising story. But the label alongside the thylacine is about the Aboriginal Tasmanian people, who were the target of a genocide. “I was aghast by how popular the story of the thylacine and its extinction is, with no mention made whatsoever about the Tasmanian genocide,” Das says. “It was the same story happening at the same time, except the Tasmanian people are not animals.”

Another glass case, empty, holds only a note acknowledging how the Grant Museum has benefited from the profits of slavery.

Das received mixed feedback from her colleagues and researchers actively working in decolonization “Their reply was that it doesn’t go far enough,” she says. Some thought the labels could be more direct statements, outside of the quintessentially neutral museum voice. For example, the shipworm text mentions the empire’s ships, but not slave ships specifically. This is, perhaps, understandable, considering the displays had to meet the approval of the museum, which insisted on a very high standard of evidence for any connections that were made. “If you want to tell them, you’ll have to be able to prove it,” Das says she was told. In some cases she struggled to make certain connections—such as slavery and shipworm—explicit.

There is no easy road to decolonizing any kind of museum—art, natural history, or otherwise. “Decoloniality is also challenging because it is necessarily unreachable, necessarily indefinable,” writes Sumaya Kassim, in an essay published in Media Diversified, an online magazine dedicated to representation in the United Kingdom’s media. “The legacies of European colonialism are immeasurably deep, far-reaching and ever-mutating, and so decolonial work and resistance must take on different forms, methods and evolve accordingly.”

Accordingly, Das and Lowe have no five-year plan for next steps in their work. But they remain engaged in the cause. Displays of Power is open until March 2020, at which point Das hopes the labels will be incorporated into the museum’s permanent text. “We don’t want temporary exhibitions. We want permanent exhibitions,” Lowe says. “We want it to be part of the workflow, so that you don’t have to think about decolonizing anything.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook