Found: The Grand Canyon’s Oldest Vertebrate Fossil

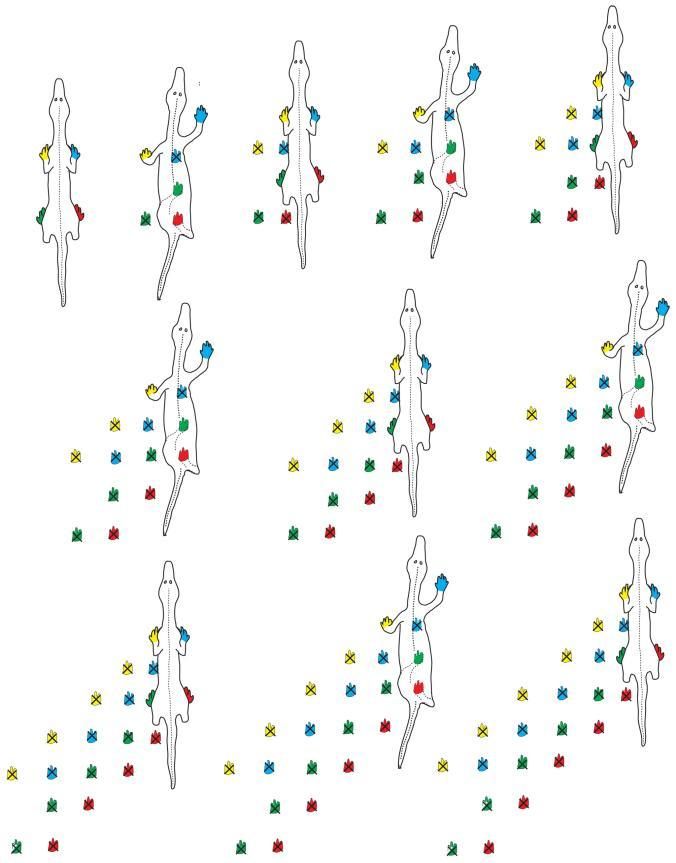

These 28 footprints were made 310 million years ago.

Eons ago, somewhere on Earth, a prehistoric lizard-like creature crept across a wet sandy dune next to a shallow continental sea. Around 310 million years later, a photo of the lizard’s fossilized footsteps was on the paleontologist Steve Rowland’s desk in Nevada.

The footsteps were preserved in a piece of sandstone along the south rim of the Grand Canyon. In the spring of 2016, a colleague of Rowland’s was walking along the Bright Angel Trail when he saw a rock beside the path with 28 strange indentations on it. He gave his friend a call.

“I have a kind of a network of hikers and geologic colleagues who know what I’m interested in,” says Rowland, who works at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. In this case, Rowland’s interest is fossilized footsteps, also known as “trackways”: the preserved memory of animals’ movements across the land. “It’s a sequence of unlikely events that happened to preserve this particular animal on a particular day in just the right conditions,” says Rowland.

It goes like this: An animal walks on a wet sand dune, dry sand fills in the indentations, millions of years of geologic forces turn the sand into rock, continents shift, the Grand Canyon forms, a rock falls off a cliff and cracks open in just the right way alongside one of the most popular hiking trails in America, a paleontologist happens to notice it and calls Rowland.

After examining the fossil, Rowland was surprised to discover he was looking at the oldest vertebrate fossil ever found in the Grand Canyon. The long skinny toes with little claws at the end suggested the footprints were left by a reptile, which was also unexpected.

“I don’t absolutely know that it was a reptile, but I think it was,” says Rowland. He says if he’s right, this could be one of the oldest records of reptiles in the world. This fossil is from a time when Pangea, the supercontinent, was forming—over 60 million years before the first dinosaurs. “Reptiles were just first evolving and appearing on Earth,” says Roland. “There probably aren’t reptiles much older than this.”

Another strange detail about the footprints: They’re diagonal. When Rowland first saw them, he thought it might be two animals walking side by side, but that didn’t make sense. “You wouldn’t expect lizard-like animals to be walking in lockstep,” he says. He reverse-engineered the footsteps to determine the animal was walking at a 40 degree angle—walking toward the right even though it was headed forward. “It was sort of sliding sideways, like it was doing some kind of line dance,” says Rowland.

There is no obvious reason for the sideways walking, says Rowland. Maybe the animal was being blown by wind or scrabbling up a steep slope. Maybe it was doing some sort of dance move to intimidate a predator or impress a mate. It’s impossible to know.

This type of guessing is exactly what trackway paleontologists are all about. While many fossil experts study bones or body parts to investigate anatomy, diet, or evolutionary history, paleontologists like Rowland who study “trace” fossils, the fossil remains of what animal left behind, are curious about how animals move and interact with the landscape. “We’re actually examining the behavior of the animal,” he says. “We can see evidence of an animal moving sideways, and you’re never going to see that in the bone record.”

By studying these footprints, Rowland is forced to imagine the motivations of a creature whose 28 steps literally stood the test of time.

“There is an animal that lived 310 million years ago and left some footprints,” he says, “and I am the person who has the privilege and responsibility of studying them and trying to interpret what they mean to the rest of the world.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook