The Woman Preserving a Beloved Bean Collection

The “Friends of Sam Birch” plant dozens of bean varieties each year.

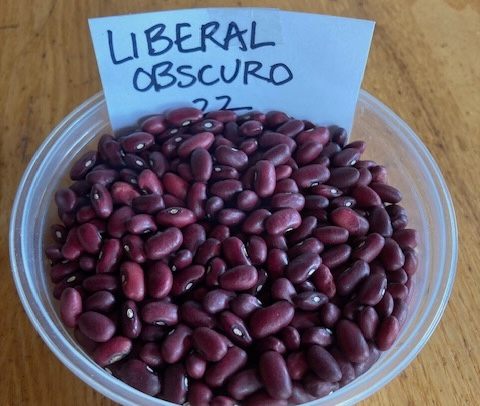

Liberal Obscuro is not an Atlas Obscura sister site, nor is it an indie band name.

Liberal Obscuro (or Obscurom) is a bean. And a very beautiful bean at that, with a deep purplish hue and smooth curves.

“I love that name,” Rosey Guest gushes. Another favorite of hers is the Fruhe Goldbohne bush bean, with its shocking, almost electric-yellow hue.

Guest is a retired farmer, living in the small town of Jefferson, Maine. For 30 years, she sold fruits and vegetables through a CSA or to local stores. She’s grown everything from tomatoes to hardy kiwis (tiny, grape-sized versions of the familiar fruits).

These days, though, she grows a lot of beans. “That’s kind of newer for me,” she says.

Guest runs an informal group, “Friends of Sam Birch,” that preserves and propagates one man’s remarkable bean collection. Herbert William “Sam” Birch was a science teacher and a passionate gardener, especially when it came to beans. By the end of his life, he had collected seeds for 350 different varieties.

Guest and Birch were members of the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association, and they both loved exhibiting their prize crops at local fairs. “He happened to live, like, three miles away from me,” Guest says. “Then he became an egg customer of mine. I started going to his house weekly to drop off eggs, and I started watching what he was doing with his beans.”

After his retirement, Birch began growing a number of crops, from garlic to squashes. But beans soon commanded his attention. “He just started really getting into beans and bragging [about] how huge this collection was,” Guest says. “He was starting to try and add 20 kinds every year.”

When Birch’s health started to decline, he was no longer able to spend as much time outside gardening. Guest and another friend decided to bring him his beans anyway. “We would grow them and then bring them in to Sam, and he would spend the winter sitting at his kitchen table, shelling them,” she recalls. “So I felt like he did the hard work, and we had the fun part.”

Birch died in 2017. “Oh, he was such a fun person,” says Guest. “He was so easy to talk to. He was one of those people that was pretty quiet, but he always seemed happy and always had a little twinkle in his eye.” Birch had left behind a list of all the beans he had collected, and hundreds of bean-filled tubs. Guest then decided to try and preserve his collection, the sum of a life’s work.

But first, she had to rebuild it. “I inherited this collection and it had over 300 kinds of beans,” she says. “I realized, going through all of the bins, that quite a few of them were either missing or had gotten so old, I couldn’t get them to germinate. I ended up with about 285 moving forward.” She quickly decided to “fill in the holes that were missing.”

To do this, she turned to resources like the Seed Savers Exchange Yearbook, and websites such as A Bean Collector’s Window, which is run by another passionate bean collector, Russ Crow. Meanwhile, to keep the rest of the collection healthy, she plants a lot of beans.

“I don’t try to grow all of them every year,” she explains. “I have them in a five-year rotation.” Every year, Guest and her “bean boyfriends,” as she jokingly calls them, grow 60 of the beans from the collection, planting ten-foot rows of each. When Guest proudly exhibits the dried beans at local exhibitions and fairs, she does so under the name “Friends of Sam Birch.”

The Friends of Sam Birch group consists of a handful of Guest’s friends as well as local schools with gardening programs. Guest notes that it’s an informal little society: People will plant a row or more of beans using seeds from the collection, then send some back. “What I want back in return is one cup of seed that’s nice, that I can use for planting stock,” says Guest. “And if you end up with more, which you probably will, that’s yours to keep.”

The bean collection has received local media coverage and a number of ribbons from fairs. But Guest doesn’t do it for the accolades. Part of what motivates her is expanding the collection even more, with additions like the Passage to India bean, which she picked up after her daughter’s wedding in India last year. “I couldn’t resist that,” she says. “Sometimes I think to myself, 300 beans is a lot already. Why do I still get entranced by adding new ones every year? What’s the matter with me?”

But when Guest rhapsodizes over the vibrant purple (“and I mean purple”) Succotash bean, or the maroon Mayflower bean, her passion is obvious. She hasn’t thought ahead to the future of Birch’s bean collection much, though she excitedly shares that one of his sons has signed up to become a “bean boyfriend.”

“I’m just having so much fun with it right now. I haven’t really thought about, down the road, what I should do with it,” she says. “I just turned 69, so I don’t imagine I’m going to be doing this for 40 more years or anything. When the time comes, I hope I find someone like me, who I think would be really excited [to] take it to heart and carry it on.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook