How America’s First Popular Comic Shaped the 19th Century Newspaper Wars

It also gave us dialogue bubbles.

In 1896, Richard F. Outcault, or, as he was known professionally, R.F. Outcault, found himself—from humble origins in Lancaster, Ohio—to be at the top of the New York journalism world. Commanding a huge sum of money, Outcault jumped ship that year from Joseph Pultizer’s New York World to William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, taking his work with him. But Outcault wasn’t a writer or editor or photographer—he drew comics, the first such artist to become a bona fide superstar.

It was Outcault, in fact, who invented the dialogue balloons seen in most every comic book since, and it was Outcault’s most famous creation, the Yellow Kid, a sardonic Irish ragamuffin who lived on the streets of New York City, that gave us one of journalism’s most enduring insults—so-called yellow journalism, or what we might call clickbait today.

According to a poll released this week, Americans distrust the media more than we have since 1972, when Gallup started asking. But distrust of the media—and not just presumed bias—isn’t really anything new. That’s because since their 19th-century beginnings, tabloids have been, mostly, a vessel for diversion and entertainment—you could leave the serious business to the broadsheets.

The World and the Journal (like modern equivalents such as the New York Post and the Daily Mail) were for too-good-to-check tales of everyday heroism, strident crusades, and, of course, pictures. Lots and lots of pictures. Were the stories true? Who knows. It was fun to read, though.

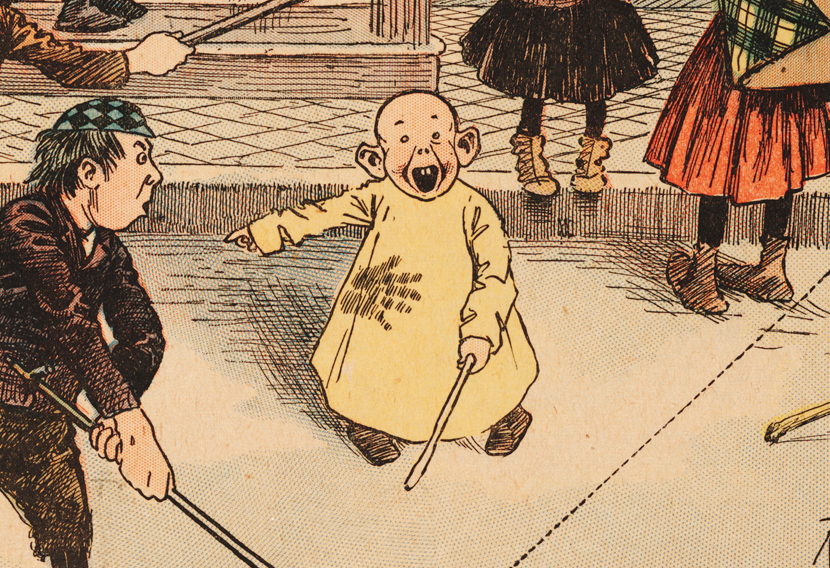

This early comic character was an Irish ragamuffin known as ‘The Yellow Kid.’ (Photo: San Francisco Academy of Comic Art Collection, The Ohio State University Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum)

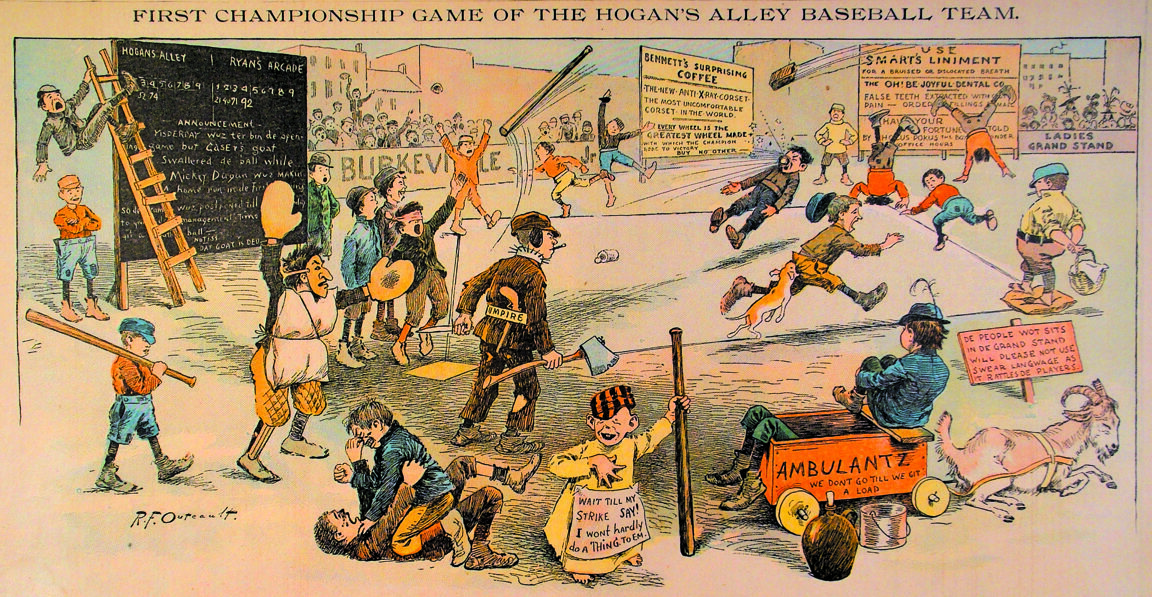

For decades, the tabloids were also, thanks to Outcault, for comics. And it was his comic that would begin the craze. Titled Hogan’s Alley—a fictional New York City slum—the comic, depending on the day, could be funny, brutal, melancholic, racist, and acerbic, sometimes all in one.

It first appeared in Truth, a magazine, in 1894, and then Pulitzer’s World early the next year, and proceeded to take New York by storm. Outcault’s comics were richly drawn tableaus of life in the slums, popular in part because you didn’t need to read the words—New York’s population then was 40 percent foreign-born— to understand what was going on. They were vulgar, violent, and sometimes explicitly xenophobic, their appeal something like that of reality television, in which readers could be an audience to the rabble, yet still a layer removed.

“If dem things is as hard on der stummick as dey is ter pernounce, dey’ll kill sure’n Coney Island whiskey,” explains one character pointing at the opening of a new French restaurant.

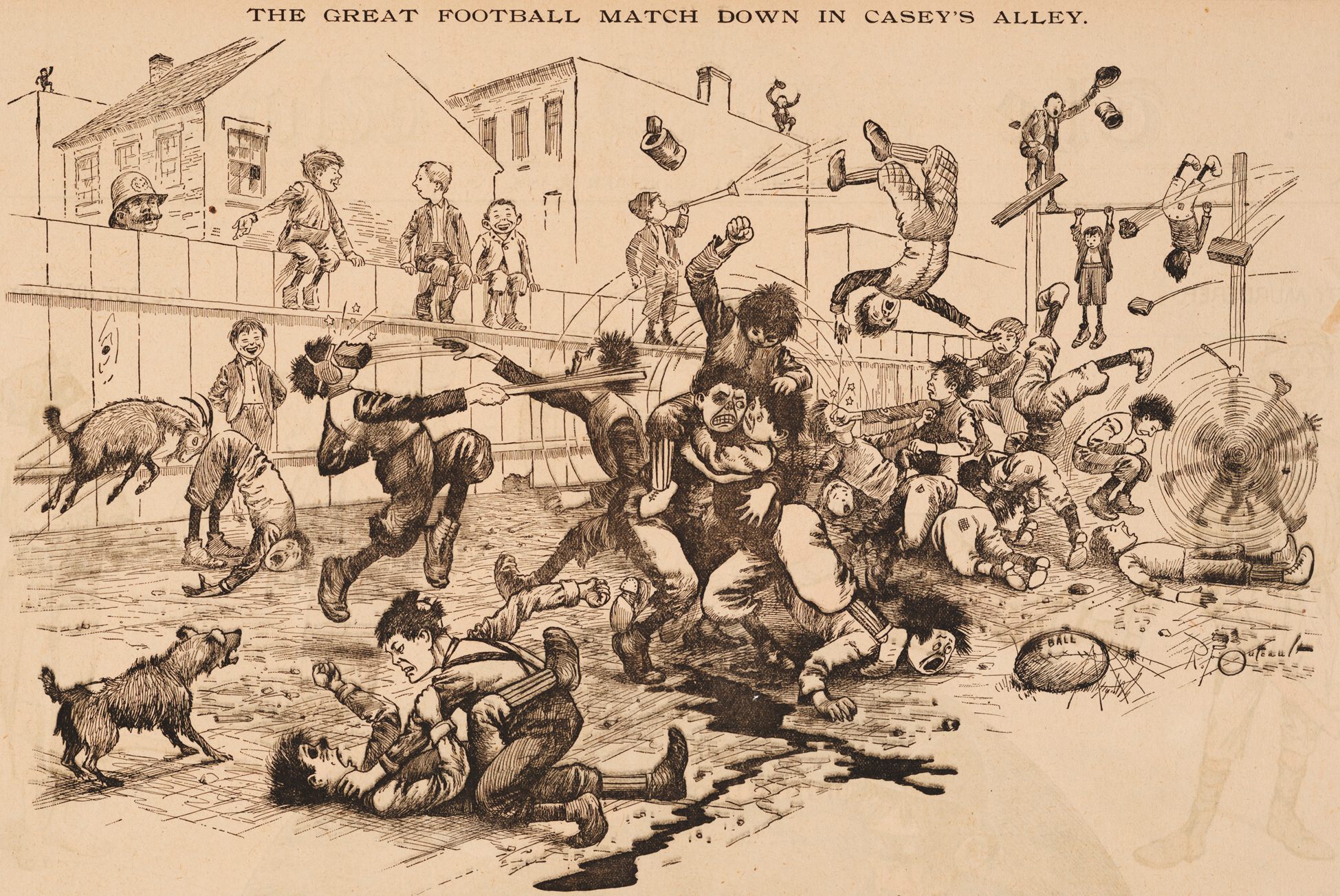

In another, which depicted “The Great Football Match Down in Casey’s Alley,” throngs of children are seen beating each other senseless with rocks, sticks, and fists.

Still, others were more docile, even sentimental, featuring about the same amount of edge as Norman Rockwell. Take one published on December 15, 1895, that depicted children frolicking in the street ahead of Christmas; one girl is seen carrying a book called “Alice in Blunderland.” (Many of Outcault’s panels can be a massive scavenger hunt of small jokes.)

Whatever their content, the comics were so popular that by 1896, Hearst came calling, and in the fall of that year Outcault took his act to the Journal. There was only one problem, though—Outcault didn’t have the copyright, meaning that Pulitzer and his World could keep producing their own rival versions of the Yellow Kid. They did just that, hiring George Luks—who would later establish himself as a painter—to keep the World’s version of Hogan’s Alley going.

“Do not be deceived,” Outcault took to signing some of his comics, “none genuine without this signature.”

The battle over the Yellow Kid occurred in the context of a brief, but vicious newspaper war between Pulitzer—who later, of course, burnished his legacy by creating the Pulitzer Prizes—and Hearst, who was the inspiration for Citizen Kane. Pulitzer was the dominant player in New York until 1895, when Hearst bought the Journal and invested significant amounts of his family fortune to try and beat Pulitzer, which, in a couple short years, he did. In addition to a series of raids on Pulitzer’s staff, Hearst’s acquisition of the Yellow Kid drove newspaper sales, meaning that, by 1897, the newspaper war was effectively over.

Happily caught in the crosshairs, of course, was Outcault, whose creation had made him wealthy, as the Yellow Kid, for a time, was everywhere, from toys to billboards to matchbooks. There was also America’s first known comic book, a collection of the Hogan’s Alley comics from the pages of the New York Journal. It was 196 pages, and cost 50 cents (about $15 today). In the ensuing decades anthologies would become a logical next step for any successful newspaper comic artist, but then it was novel. On the back of the book was a then-unfamiliar phrase. It was, it said, a “comic book.”

Within those pages contained innovations that would stick with American comics for years to come, like the speech balloons appearing next to characters, which included dialogue. Speech balloons themselves had been used for centuries, but not for dialogue, paving the way for modern American comics.

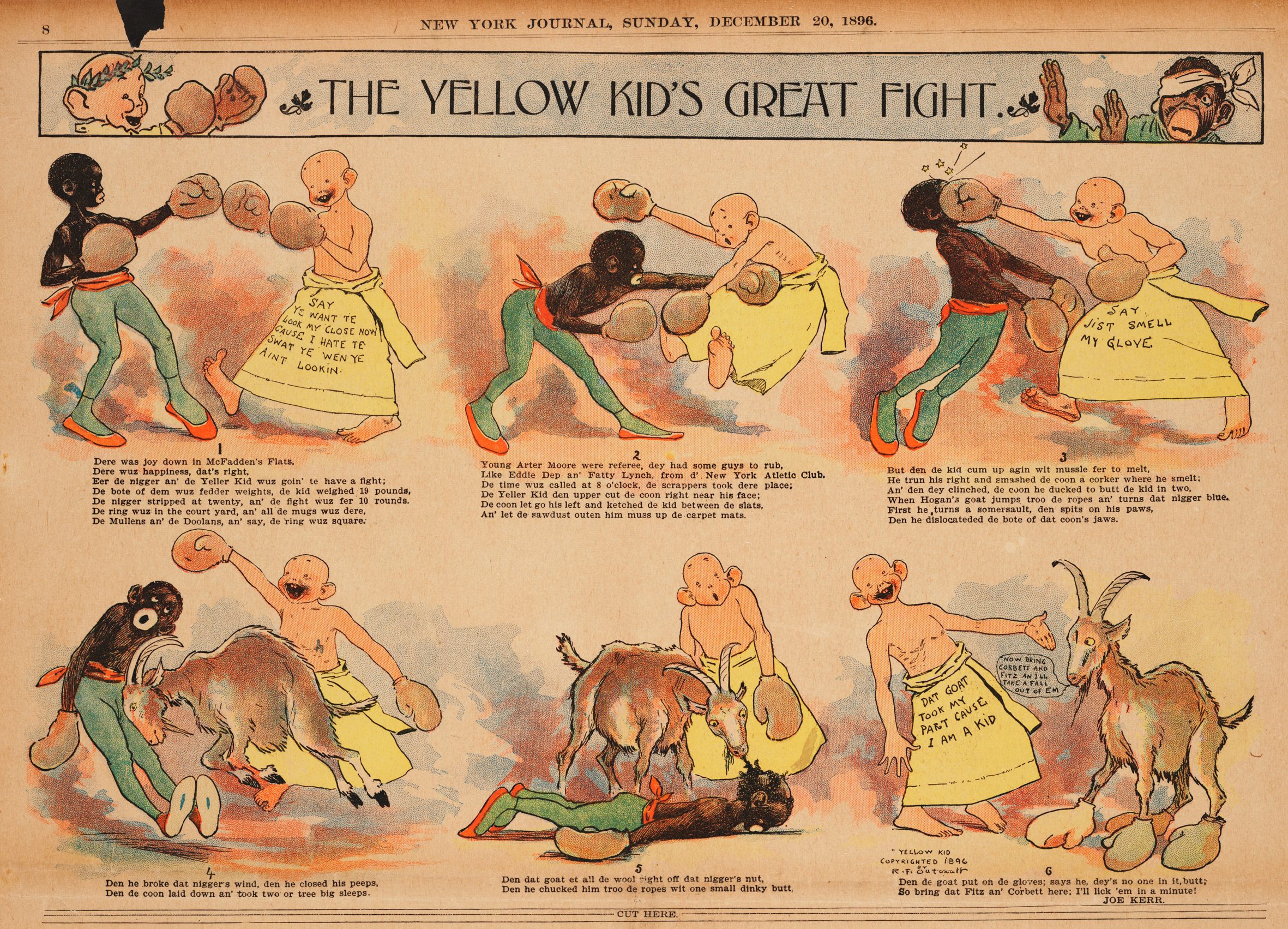

Outcault’s comics was also among the first to use panels to show action. In one comic from 1896, for example, the Yellow Kid smokes a giant cigar, which promptly makes him bedridden with sickness. (“The Yellow Kid Wrestles With The Tobacco Habit,” the strip is called.) Over the course of six panels, the Yellow Kid goes from enthusiastically curious to nearly dead.

Another six-paneled strip from that same year is more disturbing. Titled “The Yellow Kid’s Great Fight,” the strip features the Yellow Kid beating up a black boy (referred to in egregious racial terms), the reason for which is unclear. With the aid of a goat, the kid also rips the hair from the boy’s head, leaving him for dead.

The comics are relics of an era which, with its popularity and pervasiveness, it also came to define, or at least name. Outcault discontinued the strip in 1898, apparently losing interest in the character after giving up on ever getting its copyright. But the year before, Ervin Wardman, editor of the New York Press, coined a term that would stick with us today.

What to call Hearst and Pulitzer’s papers, the pirates of the genre, Wardman wondered. He considered “new journalism” and “nude journalism,” though those terms didn’t quite fit. Wardman eventually settled on “yellow-kid journalism,” which later became just yellow journalism. It stuck.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook