How to Keep a Zibaldone, the 14th Century’s Answer to Tumblr

After their invention by Venetian merchants, forms of these books were kept by everyone from H.P. Lovecraft to Thomas Jefferson.

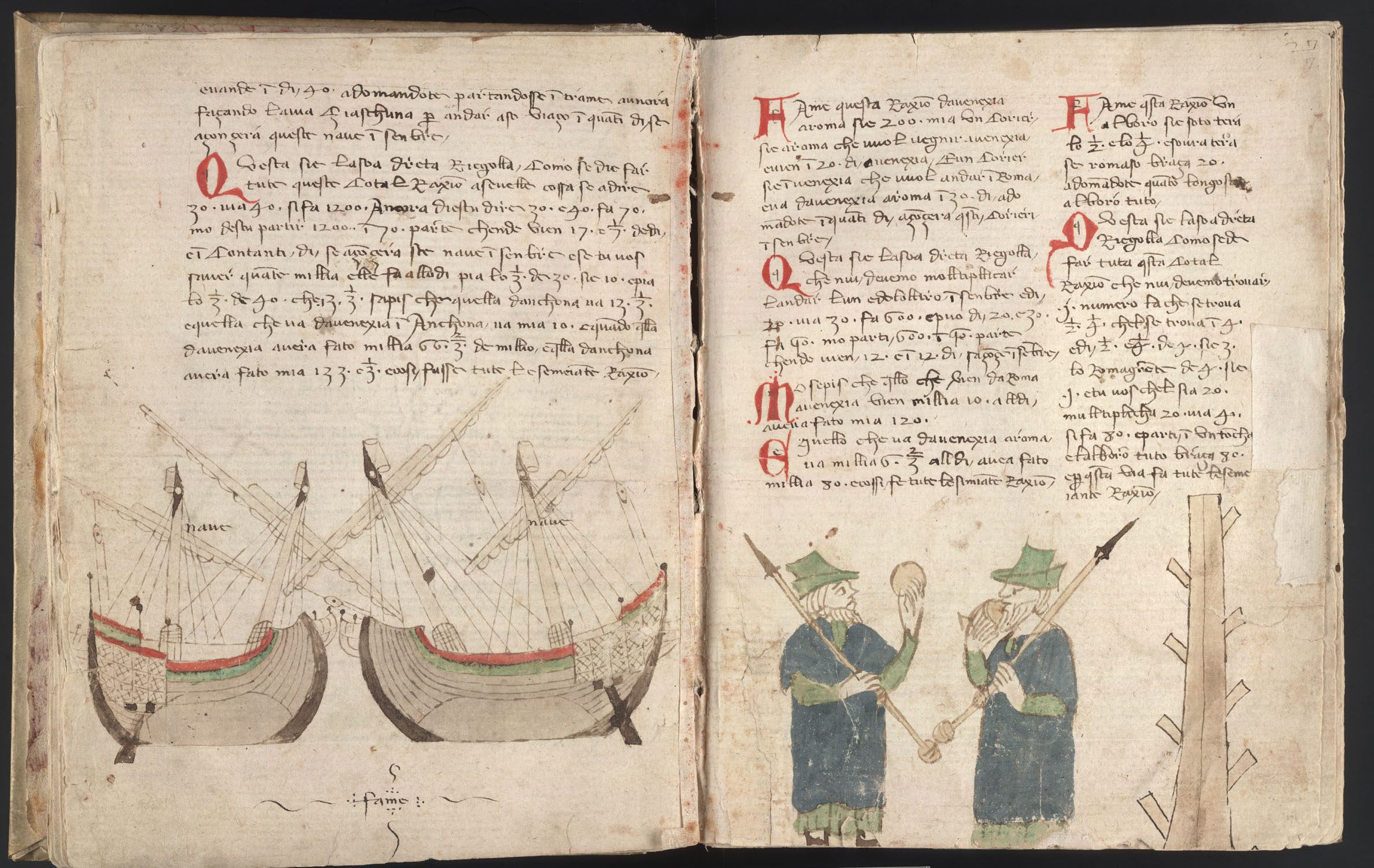

A page from the Zibaldone da Venice, a 14th-century hodgepodge. (Image: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library)

One day in Venice, sometime near the end of the 14th century, a busy merchant found himself with a few spare moments. Maybe it was a slow day at the docks, or he arrived home too early for dinner. Whatever the reason, he did what people of his era tended to do when they had some time—he took out his notebook and his set of pens, and he put together a page-sized patchwork of his afternoon.

Over 600 years later, you can still open that notebook and see that day. Written in spidery loops are daydreamy calculations regarding how large a particular tree is, and how long it might take to get to Rome. There’s a sketch of a pair of colorful ships, and another of two tradesmen in green hats, examining a meal of bread and fish. Keep flipping through, and a whole life emerges. Scribbles and sketches fill each page. Personal anecdotes and hard-won lessons nestle alongside gathered material, including prayers, copied quotations and lists of spices.

Welcome to the world of the zibaldone. A strange melange of diary, ledger, doodle pad, and scrapbook, these volumes—along with similar “hodgepodges” and “commonplace books”—served as a pattern for interior life from the 14th century onward, bringing comfort and inspiration to everyone from Thomas Jefferson to Lewis Carroll.

They helped citizens of a rapidly changing world to make sense of what they were reading, seeing, and becoming, opening the way for more contemporary recording forms, like blogging, tweeting, and sharing on Tumblr. And according to the newest generation of zibaldone fans, it may be just the right time to bring them back.

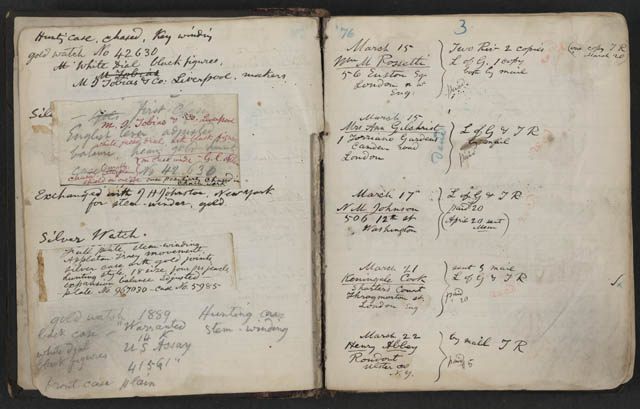

A page from Walt Whitman’s commonplace book. (Photo: Library of Congress/Manuscript Division)

Although it’s impossible to pinpoint exactly who wrote the first zibaldone, he likely resembled our daydreaming friend above. As scholar Eve Wolynes explains in “A Living Text: Literacy, Identity and Fourteenth-Century Italian Merchants in the Zibaldone da Canal,” the 13th and 14th centuries saw a sharp ramp-up in literacy among middle-class merchants, accountants, and artisans. Unlike their upper-class counterparts, who mostly stuck to Latin, these tradesmen wrote in the Italian vernacular; they also were more likely to crib together all kinds of work and play into one small, portable book. They called each volume a zibaldone, Italian for “a heap of things,” possibly after a type of mixed-up stew.

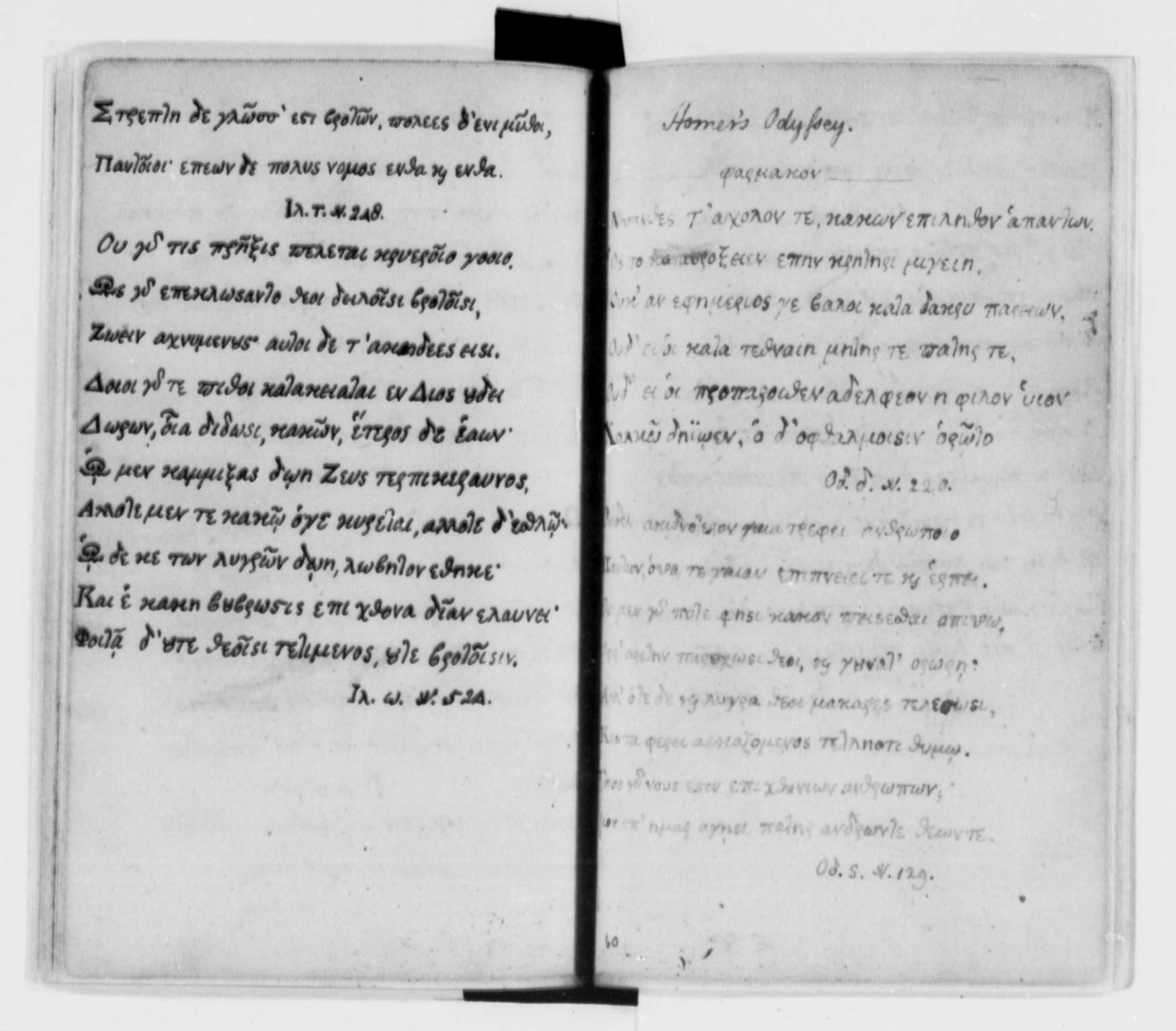

As the merchants traveled Europe, so did this invention—which, like most good ideas, fused with others that had arisen elsewhere. In Ancient Greece, Aristotle had suggested his students keep scrolls of notes from their studies, organized by subject, so that they could return at will to any topic’s “place.” Renaissance-era teachers resurfaced this idea, and by the 17th century, students at Oxford were required to keep “commonplace books,” organized notebooks stuffed with useful texts from elsewhere.

Meanwhile, back in Italy, a young poet named Giacomo Leopardi lent the genre a new whiff of literary integrity. Leopardi, who died young, was both brilliant and gloomy—at least one modern scholar has compared him to Kurt Cobain—but mostly, he was prolific. His Zibaldone di pensieri begins with a moonlit encounter with a barking dog, and launches into 2,000 pages of frustrations, insights, poetic fragments, and copied passages. After him, the zibaldone was no longer a stew. It had become, in the words of another high-minded hodgepodger, “a salad of many herbs.”

Thomas Jefferson had two commonplace books—one for legal matters, and one for literary ones. This page from his literary book contains a painstaking copy of Homer’s Odyssey. (Photo: Library of Congress/Manuscript Division)

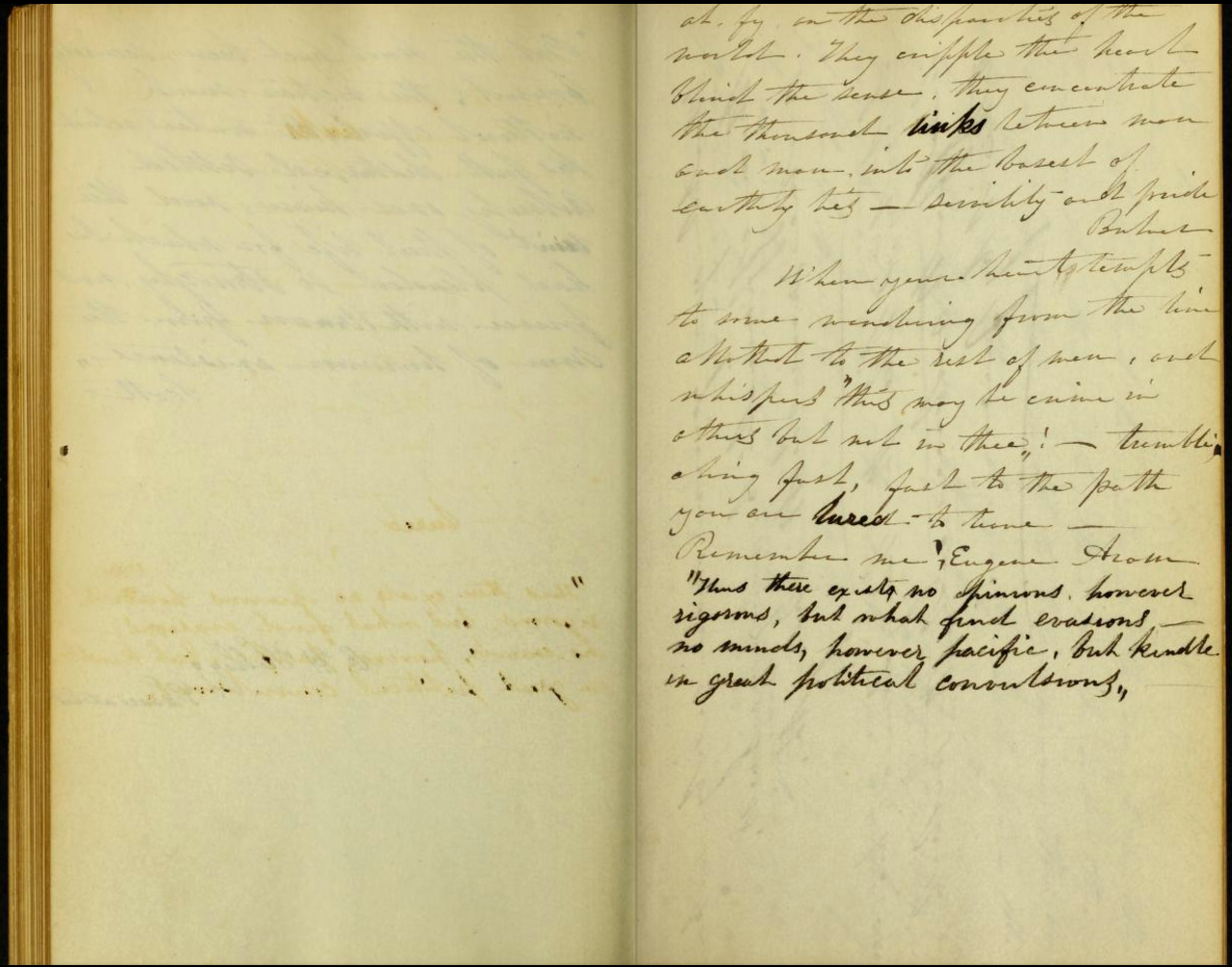

This heady combination of usefulness and prestige meant that by the 19th century, pretty much every serious literary figure traveled with a notebook and pen specifically for zibaldoning. Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau collaborated on a commonplace book, collecting and sharing poems they each admired. Oscar Wilde wrote down his own favorite aphorisms, and Lewis Carroll spent a lot of time sketching exacting labyrinths. H.P. Lovecraft’s book is filled with germs of horror stories, abbreviated “Hor. Sto.” and tucked among quotations from Hawthorne and the New York Times. (“Hand of dead man writes,” reads one story in its entirety.)

Non-literary types weren’t spared, though. At least one scholar has argued that Carl Linnaeus came up with his taxonomic system because he was so used to thinking like a hodgepodger. The commonplace book of William Byrd II, founder of Richmond, Virginia, is full of scripture, meal logs, and 18th-century sex tips, all of which have proved fruitful to modern scholars hoping for a glimpse at colonial American life. The British sailor Henry Tiffin shows up in zero history books, but filled his own book with 28 years’ worth of sea shanties, ship notes, and gorgeous watercolors.

A page from Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s commonplace book, kept from 1831 through 1841. (Photo: Archive.org/Public Domain)

Today, it’s a rare layperson who keeps a notebook like Tiffin’s. But it’s also hard to find anyone who doesn’t have some type of hodgepodge, whether in the form of a Twitter timeline, a Pinterest board, or an smartphone notepad. In fact, some media scholars argue that commonplace books and zibaldones were precursors to the Internet, which is similarly scrappy and mixed-up, rich in influences and perfectly willing to zig-zag between genres.

“It’s sort of built into the web,” says Deb Chachra, an assistant professor of materials scientist at Olin College. “Bookmarks were added to browsers very early, so there’s always been a way to get these breadcrumbs in an online space.”

Chachra does a lot of online record-keeping—”Pinboard is my commonplace book,” she says—but she also has a decade’s worth of physical zibaldones on her desk, which she uses to store stray thoughts, quotations, and ephemera. “It’s the place that has the intellectual things that I’m going to come back to,” she says She flips through her current one while on the phone and, again, a picture of a life emerges: a ticket for a colliery mine tour, a Margaret Atwood poem, stickers from the British Museum.

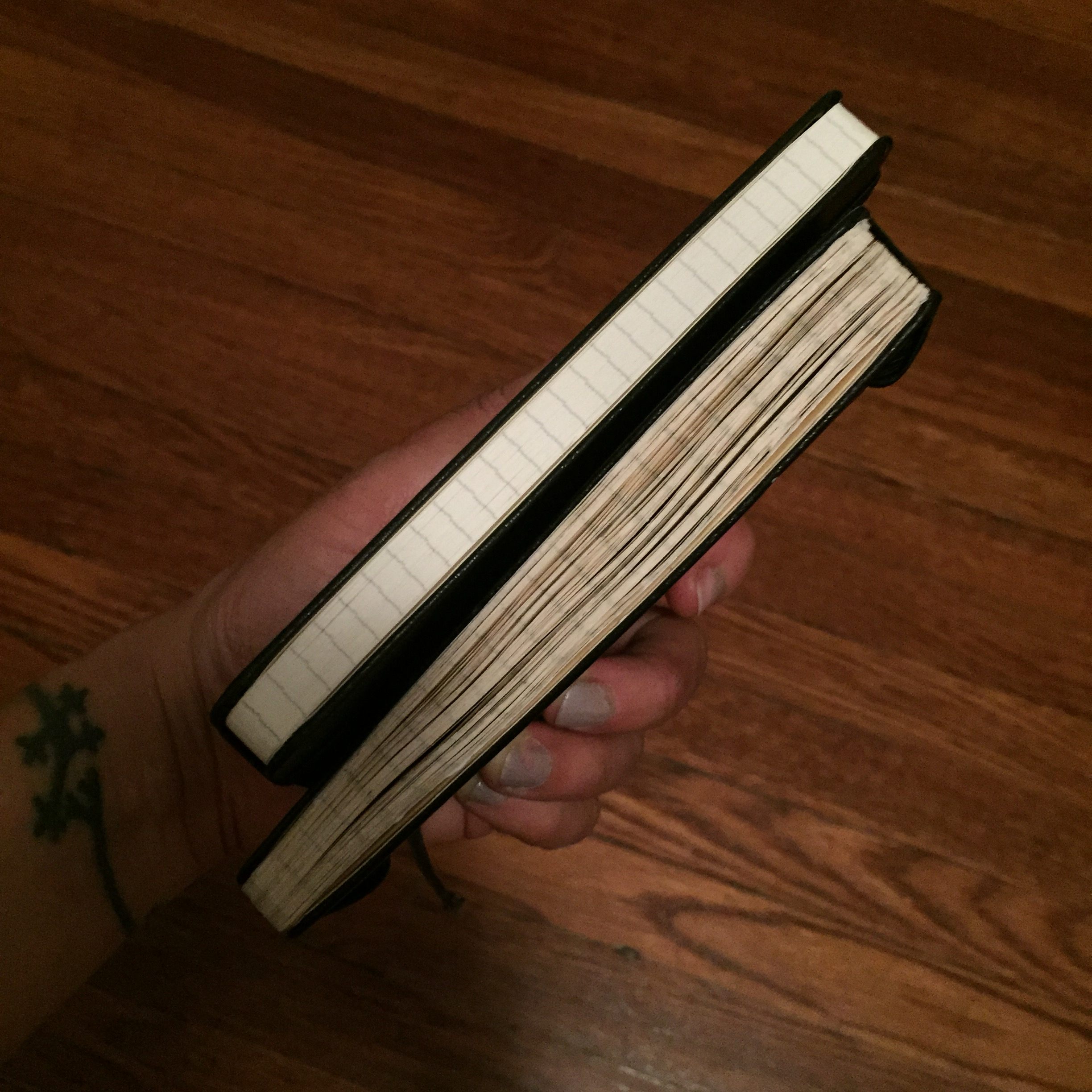

Two of Deb Chachra’s zibaldones—a full 2015 one and an empty 2016 one—at the turn of the new year. (Photo: Deb Chachra)

Chachra mostly reads books on her Kindle, so after she finishes one, she’ll write a squib about it in her zibaldone. That way, she can feel its continued presence somewhere, even if not on a shelf. She’ll do the same for films and concerts. “Having physical mementos of experiences is not a new thing,” she says, but in a world of cell phone photos and saved web histories, it’s easy to forget that if we want to remember the offline parts of our lives, we’ll have to do some of the legwork.

Plus, unlike so many modern tools, it doesn’t even pretend to be about productivity. “It’s not like budgeting,” she says. “It’s more like, what am I spending my life on? What are the things that I do and that I’ve done?”

All you need to start your own zibaldone or commonplace is a blank notebook, a pen, an open mind, and maybe a roll of tape. But if you’d like inspiration from those who came before, you might turn first to Erasmus of Rotterdam, a Dutch humanist committed to embracing the muchness of life. In his De Copia, from 1512, he lays out a rich trove of bookworthy discoveries.

“Whatever you come across,” he writes, “you will be able to note down immediately… be it an anecdote or a fable or an illustrative example or a strange incident or a maxim or a witty remark or a remark notable for some other quality or a proverb or a metaphor or a simile.” You can feel him savoring the possibilities, as though he’s ogling a dessert buffet.

Giacomo Leopardi’s Zibaldone di pensieri, on display at the National Library of Naples. (Photo: Carlo Raso/Public Domain)

These scribes’ scribes also have practical tips. If you want a strictly thematic commonplace book, advises Erasmus, try preparing your topics ahead of time, so you know where to put everything you come across. (He suggests starting with “impiety” or “strange cults,” but your mileage may vary.)

But organization is far less important than commitment. Virginia Woolf hammers this home in her 1917 essay “Hours in a Library,” in which she refers to “those old notebooks which we have all, at one time or another, had a passion for beginning”—emphasis on that last word. “Most of the pages are blank, it is true,” she continues. “It suddenly stops in the month of June.”

I considered copying down this quote, and filing it in my commonplace book under “pure cheek.” But instead I wrote out one from Leopardi, still the form’s truest advocate. “You learn about a hundred pages a day about how to live,” he wrote in his own zibaldone, about halfway through adulthood. “But the book (this book) has 15 or 20 million pages.” Time to start filling them in.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook