Why Ireland’s Pub Owners Have Long Moonlighted as Undertakers

It helps to have cold storage and room to hold a wake.

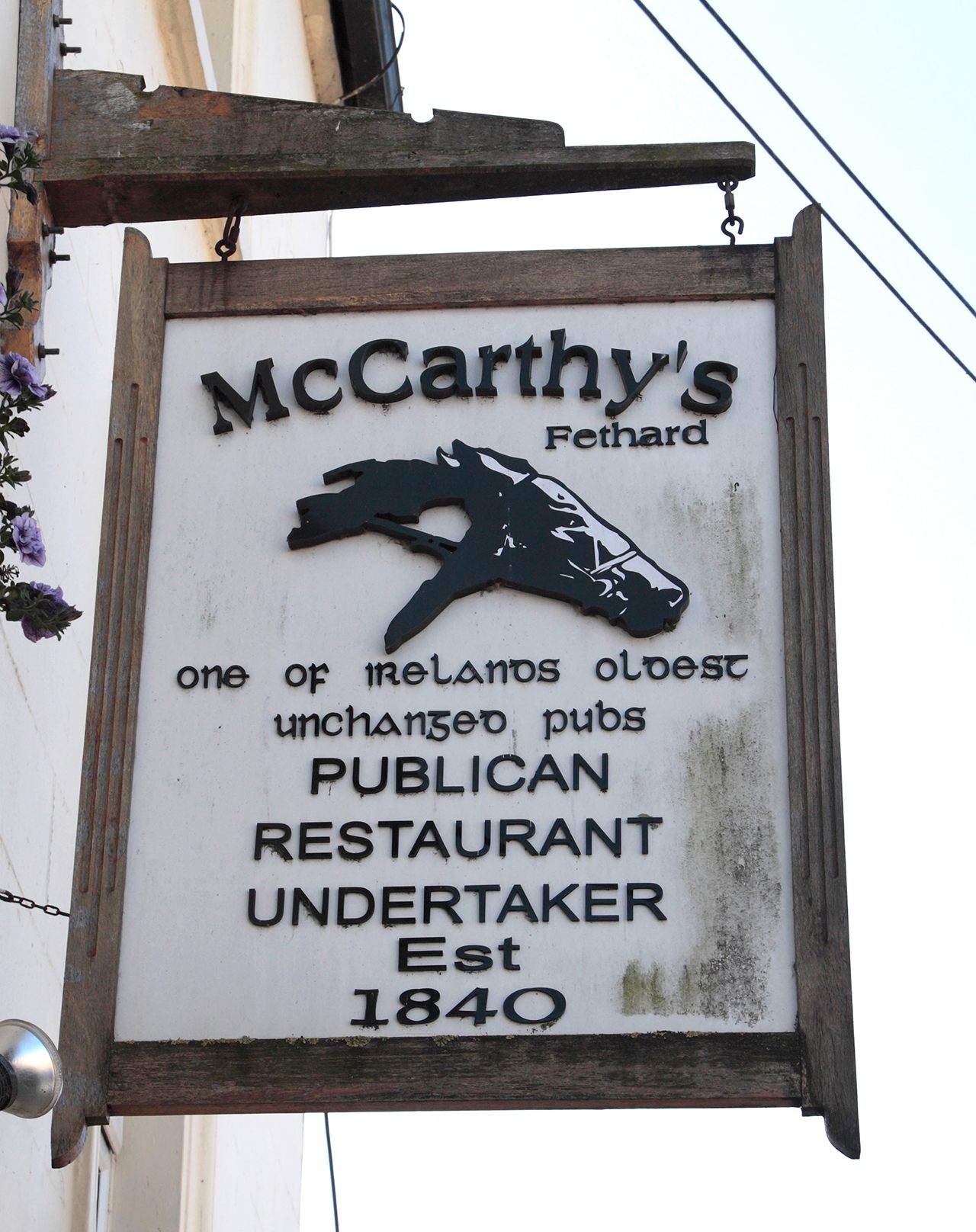

Jasper McCarthy, the fifth-generation owner of the pub that carries his family’s name, pulled his first pint at the age of 10 and buried his first body three years later. For nearly two centuries, the McCarthy family has been serving Irish spirits in Fethard, a quaint village in County Tipperary fortified by a 13th-century stone wall. A hearse is now parked in the old livery stable out back, but otherwise little has changed at McCarthy’s Pub, Restaurant, and Undertakers since it was founded in 1840 by Michael McCarthy, Jasper’s great-great-grandfather.

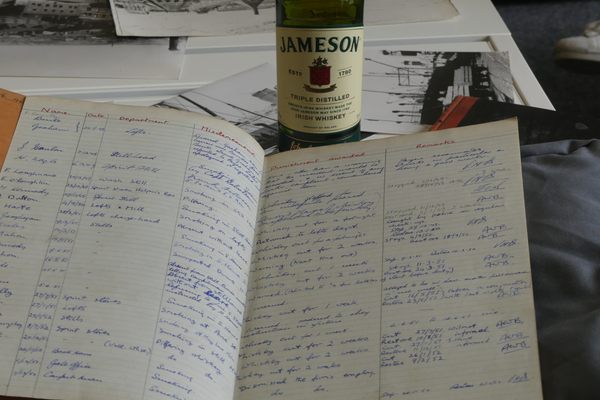

The worn wooden walls, textured by tobacco smoke and time, are adorned with faded photographs, decades-old newspaper clippings, and horse-racing memorabilia. Funeral ledgers, dust-covered and peeling with age, are stacked haphazardly on antique grocery shelves. A cast-iron stove fights the chill of the Irish winter and partitions called snugs, set with stained glass, frame the front section of the bar. Traditionally, these nooks were for women, who were not permitted, by policy and propriety, to drink in the main bar. The frosted glass on the front door reads “McCarthy’s Hotel and Pub,” though the former has long since closed.

McCarthy’s is not the only pub in Ireland that serves beer alongside burials, but it is one of the last. This seemingly unusual commercial pairing used to be quite common, but has steadily declined since funeral homes were introduced in the late 1960s. “It wasn’t uncommon for a publican to combine undertaking with their normal day-to-day business 50 or 60 years ago, but the number has declined over the years,” says Tom Coburn, a longtime casket supplier. “Throughout the Republic of Ireland there are maybe 100 publicans that also still do the undertaking.”

“In my home town of Newry, there were three public houses/undertakers within 50 yards,” writes Iain Harkness of East Lothian in a column in the Irish Daily Mail. “As children, we would play among the beer barrels and coffins out the back.”

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the dual role flourished in rural Ireland, where publicans often ran multiple businesses from the same premises to compensate for low foot traffic. “Back then the local publican was a general factotum. He just did everything, including the undertaking,” says Coburn. Country pubs doubled as groceries, butchers, hardware stores, carpenters, and of course, undertakers. “You could buy anything in a pub, from a needle to an anchor,” recalled Tommy O’Neill, a carriage driver from Dublin, in Dublin Pub Life and Lore: An Oral History. For example, Michael McCarthy was listed in a 1889 business directory as a baker, grocer, spirits dealer, draper, and post car and hearse driver.

Since the early 18th century, pubs have been deeply woven into the fabric of Irish political, social, and economic life. “At the time there were no community halls or neighborhood meeting places. So therefore, all social, recreational, political, and economic activities were concentrated in the pub,” says Eamonn Casey, a pub historian and author of The Dublin Pub Saunter. With so much of a community’s life centered in the pub, it was natural that they would also play a prominent role in death.

“The publican was the man who christened them, married them, and buried them, the local people,” said John O’Dwyer, a Dublin publican, in Dublin Pub Life and Lore.

In many ways, the combination of publican and undertaker was natural within the context of a traditional Irish wake. Up until the middle of the 20th century, wakes were raucous, multi-day affairs where alcohol flowed freely and traditional taboos were temporarily suspended. “It was very convenient for the family,” explains Coburn. “At a traditional Irish wake there would be a lot of drinking done to give the deceased a good send off and a bit of a party.”

Traditionally, locals looked to the publican to provide alcohol for the wake—and money for the funeral. “If there was a death in the family they always depended on one person [to] go to the publican for a loan of money for the funeral,” noted Mikey Boy, from the Liberties district in Dublin, in Dublin Pub Life and Lore, “And always after the burial there was a good session [at the pub].”

Pubs always had a place in commemorating the dead, but the actual foray into undertaking can be traced back to the Great Famine in the late 1840s and early 1850s, in which an estimated one million people—one-eighth of the total population—died from disease and starvation. Mortuaries and medical practitioners struggled to keep pace with the endless flow of corpses. The bodies needed to be stored somewhere, lest they spread infection or be consumed by wild animals.

And this is where the centrality of the pub to community life returns. The Coroners Act of 1846 mandated that dead bodies be brought to the nearest public house. Publicans were required to store the corpses until an inquest was held, and those that refused were heavily fined. (Remarkably, the requirement was on the books until 1962, though it had stopped being enforced long before.) It was also a practical matter. In the days before refrigeration, beer cellars provided a cold storage space to delay decomposition. Eventually, even after the famine had passed, some pubs gained a reputation for their services and remained in the business. For example, the Templeogue Inn, which was located next to a dangerous road bend in Dublin, was nicknamed “The Morgue” because so many traffic accident victims were dropped on its doorstep.

During this time, some aspiring publicans even opened mortuaries first, since the establishments were allowed to serve alcohol. “Many pubs received licenses because they had facilities where a body could be held overnight,” says Casey. The Dropping Well Pub, located on the banks of the Dodder River in South Dublin, opened as a morgue in 1847. Shortly after, the proprietor, John, caught an infection from all the dead bodies on the premises. He died of complications in 1850.

Sensing an opportunity, some of the publicans tasked with storing dead bodies took the next logical step and developed side businesses as undertakers, which included making funeral arrangements with the cemetery, priest, and family. They installed autopsy tables and separate rooms in which to hold wakes. “Back in the late 1800s and early 1900s, families were often not in the position to host a wake,” explains Coburn. “The homes in Ireland would have been really small and sparse and not have the facilities to have a good wake.” The pub was like a home away from home. This was certainly the case at McCarthy’s. “Before we had a funeral home, bodies were waked in a side room off the pub,” says Jasper McCarthy.

As society changed, so, too, did the pub’s function within it. Increased mobility brought other stores within reach, so not everything had to be procured at the pub. Modern funeral homes and hospital mortuaries made the storage and viewing of corpses in pubs unnecessary. Irish pubs have always played a part in funerary rituals—and probably always will—but their role has expanded and contracted over time, constantly evolving to meet the needs of their communities. While the future of the publican-undertaker trade is uncertain, at least a few Irish bartenders can still properly prepare a stiff one.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our regular newsletter.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook