Leave No Black Plume as a Token: Tracking Poe’s Raven

J. W. Ocker, the author of Poe-Land: The Hallowed Haunts of Edgar Allan Poe, out now from Countryman Press, discovered a surprising array of sites and artifacts connected to Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” in his year-long trek to visit all things Poe in the many places the poet lived.

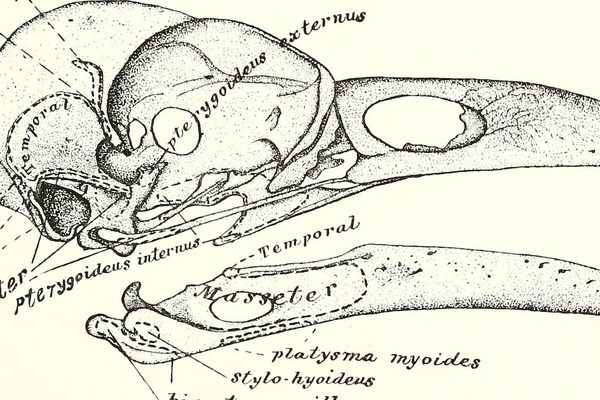

Illustration by Édouard Manet for a French translation by Stéphane Mallarmé of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1875) (via Library of Congress)

You know the image. A lone man sits in his chamber one midnight dreary pondering over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore, when his reverie is interrupted by a grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore that perches on a pallid bust of Pallas just above his chamber door.

Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” was published in January 1845 in New York’s Evening Mirror. This was less than four years before Poe died, and 15 years since he last published a full volume of poetry. Its 18 stanzas represent the peak of his fame in life. It probably still does, but that’s two very different peaks, like Bunker Hill and Olympus Mons different.

Today, “The Raven” is as relevant, well-known, and popular as, well, whatever the kids are listening to and watching these days. Sorry. I’m old. Artists and storytellers, even the National Football League, have tried to wrestle the image of the raven away from Poe’s death grip, but all have failed to even rustle a single ebon feather. Perhaps the strangest thing about this poem that started in one man’s imagination and expanded into the collective cultural consciousness is how many physical artifacts related to it have survived.

For my new book, Poe-Land: The Hallowed Haunts of Edgar Allan Poe, I spent more than a year visiting memorials, mementos, monuments, and more dedicated or connected to Edgar Allan Poe in the places he lived and visited. That meant traveling from Massachusetts all the way down to an island in South Carolina, as well as across the Atlantic, seeing amazing Poe sites and artifacts and meeting the people responsible for maintaining his physical legacy. By far, some of my most favorite sites were directly related to “The Raven,” most in surprising ways.

Once Upon a Midnight Dreary

W. 84th Street in Manhattan (all photographs by the author unless noted)

It seems like a normal Upper West Side Manhattan street. People cram the concrete, cars cram the asphalt, the kind of thick bustle of humanity you either love or hate. Until you look up and see the shiny green sign that says “Edgar Allan Poe St.” It’s a short stretch of West 84th Street, from West End Avenue to Broadway, a mere block, but the sign doesn’t honor Poe randomly. It hints at something significant related to Poe in the area. You have to lower your gaze to discover what that is.

Two different plaques, one on the side of The Alameda building at 255 West 84th Street, and one at Eagle Court Apartments at 215 West 84th Street, attest that somewhere thereabouts stood the farmhouse where Poe penned “The Raven.” The former plaque was placed in 1922 by the Shakespeare Society, the latter by a local landmark society in 1986.

Looking around the urban chaos, it’s hard to imagine the isolated farmhouse perched on its rocky crag, much less the dark man inside making a list of English words that rhyme with “nevermore.” But nearby, there’s something that can help spur the imagination.

Each Separate Dying Ember Wrought Its Ghost Upon the Floor

Butler Library at Columbia University

Columbia University is a mile and a half north of Edgar Allan Poe Street. There, in the rare books department of Butler Library, a building that has Poe’s name carved on its façade along with many other founding literary fathers, is an amazing artifact.

Located in a short, thin, white hallway across from a series of glass-walled offices is a black fireplace mantel. It would have been easy to walk right past it had I not been directed to it, and even easier to miss the tiny brass plaque affixed to it, with its brazen statement, “EDGAR A. POE wrote THE RAVEN before this mantel.”

The farmhouse where Poe wrote “The Raven” was torn town in 1888, four decades after his death and long enough after for his fame to spread. A fan named William Hempstreet pulled the mantel from oblivion, and 20 years later donated it to Columbia University.

Two chairs sit in front of it, and of course, I sat in one to read the copy of “The Raven” that I had brought, savoring particularly the line “Each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor,” as it may well have been the fire within that very mantel that inspired it.

From My Books Surcease of Sorrow

The Free Library of Philadelphia

In Philadelphia, there are two main places you can go to search out Poe in general. The first is his home, a National Historic Site, which has no real relation to “The Raven,” although in its basement is a plaque declaring that the poem was written there. The idea is actually semi-defensible, but generally not held. It’s left over from the previous owner — wealthy grocery story scion Richard Gimbel — who was a little too zealous in his love of marketing Poe. To really see something related to the poem, you must head to the Free Library of Philadelphia’s Central Library, where Gimbel’s full collection of Poeana resides. And, really, you must.

“The Raven” in Poe’s writing

There, in the rare books department on the third floor, accessible by advance request, is the only extant, full copy of “The Raven” in Poe’s own handwriting. It covers two sheets front and back, and was written at the request of a fan who lived in Phoenixville, Pennsylvania.

But as amazing as that manuscript is, the Free Library tops itself when it comes to “The Raven.”

Stately Raven of the Saintly Days of Yore

On display in a glass case just down the hall from where I got to hold “The Raven” manuscript in my hands is a taxidermied raven. Its story is going to be a hard one to stuff in a nutshell.

Grip the Raven (via Atlas Obscura)

In short and inadequately, that piece of bird-wrapped sawdust is Grip the Raven, a pet of Charles Dickens that he used, along with another of his pet ravens, as the model for the talking raven in his book Barnaby Rudge. Poe reviewed that book for one of the magazines that he worked for, noting the use of the bird in particular and expressing the wish that its utterances had been used more prophetically. A few years later, “The Raven” was published, with its “Prophet!…thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!”

Basically, that dead bird flesh under glass was muse to two of the greatest writers in the language. I can barely believe it exists, much less that it’s publically accessible. A highlight of my entire Poe trek, no doubt.

On This Home by Horror Haunted

People loved “The Raven” enough that Poe was often asked to read it in front of lecture audiences and at social gatherings. The last time he did so was in the city where he grew up — Richmond, Virginia — in a farmhouse called Talavera. It was the home of a friend of Poe’s sister Rosalie, who lived most of her life in Richmond. Poe was enjoying a triumphant return to that city, famous at last for his work and all the shadows that marred his youth there long dispelled. Two weeks after his reading, Poe died under mysterious circumstances in Baltimore while en route to Philadelphia.

The yellow house still stands, although it was moved from its previous location to what is now 2315 W. Grace Street in a charming Richmond neighborhood. The privately-owned house bears no sign that attests to the fact that it’s one of the few places Poe can be tracked in the last weeks of his fever called living.

Be That Word Our Sign of Parting

We’ve all heard the lines of “The Raven” so many times that they can blast right past us like those rock songs from the 1960s and 70s that got played too many times on FM radio over the years. To see the sites connected to the poem anchors the words and imagery, slows them down to the meticulous scratching of a real pen against real paper, adds a new angle for us to approach it to help us continue to appreciate this poem. After all, it’s not going anywhere.

And that Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting.

J.W. Ocker is the author of The New England Grimpendium and The New York Grimpendium, both personal travelogues of deathly sites in those regions. He also runs the website OTIS (www.OddThingsIveSeen.com), where he chronicles his visits to oddities of culture, history, art, and nature across the country and world. Poe-Land: The Hallowed Haunts of Edgar Allan Poe is available now.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook