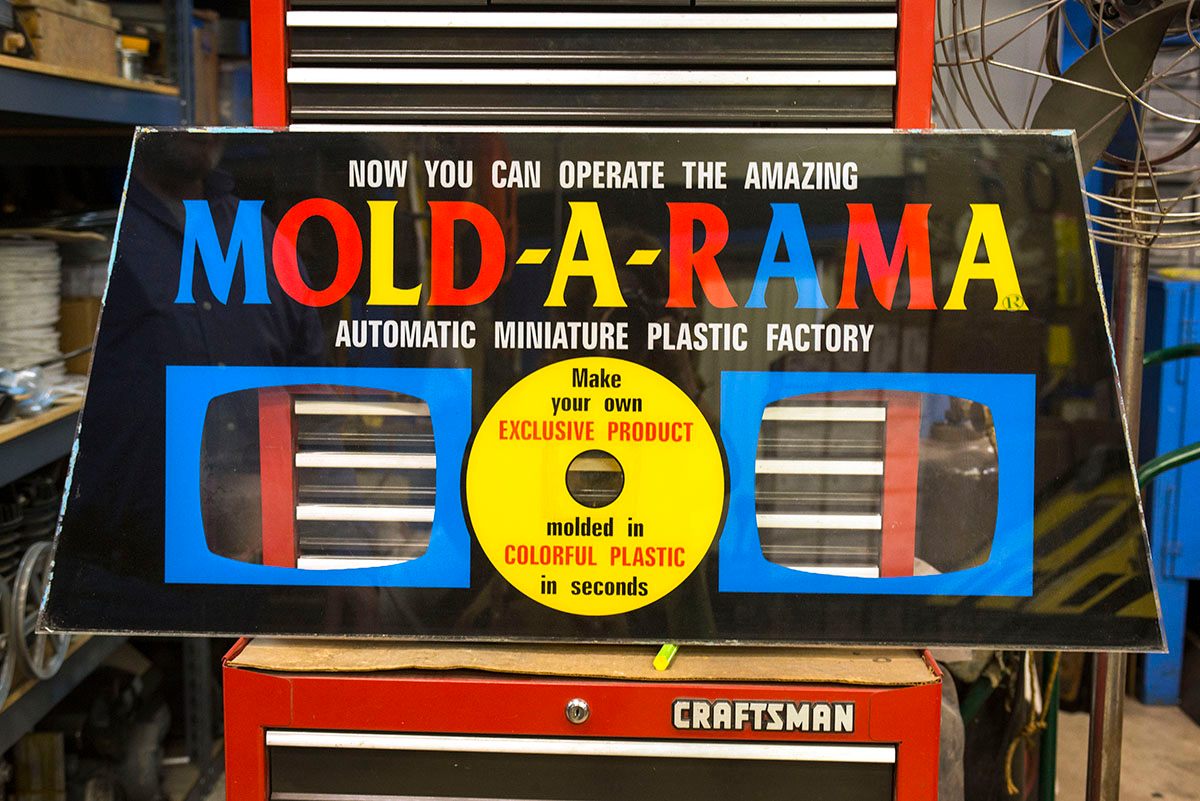

Meet the People Keeping Mold-A-Rama Alive

These retro machines, which make plastic souvenirs right before your eyes, are as popular as ever.

In 1971, sick of working in middle management in Chicago, William Jones purchased a number of Mold-A-Rama vending machines on a whim. He knew nothing about the technology, which produces injection molded plastic figures, and didn’t understand its appeal, but saw the purchase as an opportunity to do something new for a living. Little did he realize that almost 50 years later, his family would still be in the business, maintaining a collection of the beloved machines, which are as popular as ever at zoos, museums, and other attractions across the United States.

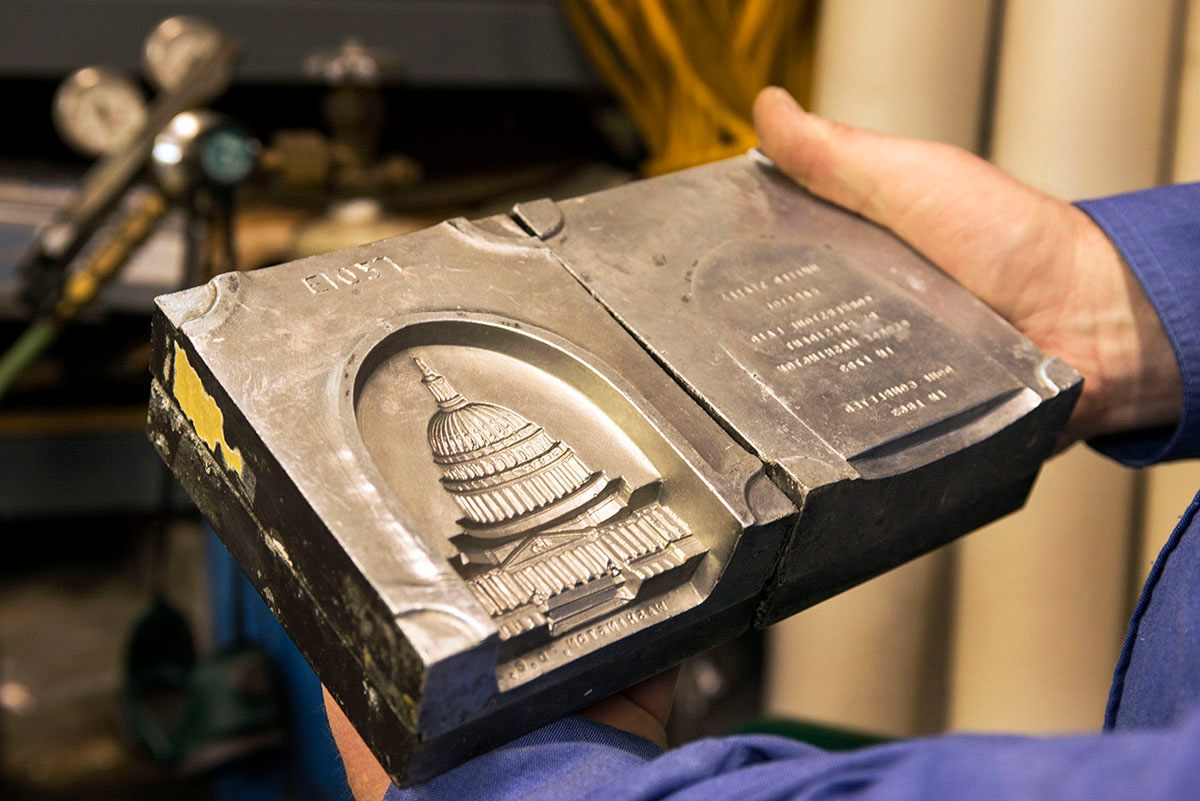

When Mold-A-Rama debuted at the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair, the molds of the Space Needle, a monorail, and other fair-related designs drew as much attention as the unique production process, which remains the same to this day. After inserting payment, customers watch two sides of an aluminum mold close as it is injected with heated polyethylene pellets. In less than a minute, the mold opens, releasing the plastic object.* The signature “waxy” smell hangs in the air as the hollow figurine slowly cools.

It’s not only nostalgia for the figures but this same, seemingly outdated process that keeps Jones in business. In an age when technology allows souvenirs to be more personalized than ever (see Japan’s purikura machines), the Mold-A-Rama’s simplicity is appealing both for those who grew up with the machines and new fans.

The Mold-A-Rama was the result of decades of work by J.H. “Tike” Miller of Quincy, Illinois, according to a history of the company in Mental Floss. Miller began experimenting with miniatures in the late 1930s. It wasn’t until World War II that he found a lucrative niche in plaster nativity models when imports from Germany—the largest supplier of these religious figures—were blocked. In 1955, he switched to producing figurines through plastic injection molding. An eccentric, he became known for molds of dinosaurs, aliens, and even a Purple People Eater.

“[Miller] was one of the pioneers in the plastic era and stands out from all the rest with his unique way of molding plastic and the unique composition of the plastic material that he used,” says Ken Glennon, a Mold-A-Rama collector who is writing a book about Miller.

During the mid-20th century, after Miller licensed the technology to Automatic Retailers of America, the memorabilia took off at national and international fairs with about 300 molds in use. What set Mold-A-Rama apart from other toys and souvenirs at the time was that it gave customers insight into the products’ manufacturing, as it was happening, decades before 3D-printing.

William’s son Paul Jones now runs the company, which was known as the William A. Jones Co. until 2011, when the name changed to Mold-A-Rama Inc. He remembers helping his father service Mold-A-Rama machines at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry and Brookfield Zoo. By 14, he was getting to the zoo by 6 a.m., which he says “was like heaven. You get to run around. You get the whole zoo to yourself.”

Now in his 50s, Jones travels the Midwest maintaining 62 machines at nine locations, including the Willis Tower, the Field Museum, and the Henry Ford Museum of American Innovation. Much of the machine’s appeal is the retro look; in 2006, William estimated that one in 10 people who pass a machine buy a toy. In addition to regular cleanings and occasional paint jobs, a major challenge is ensuring that the Mold-A-Rama produces a perfect product almost every time.

Although some people assume the Mold-A-Rama is as simple as a vending machine, dispensing pre-made figurines, “it actually holds a gallon of hot liquid plastic all day long at 250 degrees [Fahrenheit],” Jones says. Small changes in temperature or the number of toys produced can affect quality. On a popular day, one machine makes 100 to 150 toys.

Only minutes from the Brookfield Zoo, the Mold-A-Rama warehouse is packed with out-of-commission machines and parts. Rows of repurposed Cheese Ball jars are full of clear plastic pellets mixed with dyes that melt together to create the vibrantly colored souvenirs. Jones estimates he goes through 640 55-pound bags of pellets a year.

Jones also has an archive of more than 200 cast aluminum molds, including the 62 currently out in the field. He even owns some of the original molds, which were on display at the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962. His collection ranges from cute animals, such as a cartoon dolphin and piggy bank, to geographic-specific memorabilia, such as a San Francisco streetcar and the Houston Astrodome. During the holidays, he offers seasonal designs, including Santa Claus and a Christmas tree. He also has busts of all of the U.S. Presidents, up to John F. Kennedy. As Jones says, almost anything can be made in miniature.

Glennon says the internet has played an important role in Mold-A-Rama’s continued popularity, with rare figurines selling for hundreds of dollars online. Designs that are difficult to produce, such as a replica of Colleen Moore’s Fairy Castle at the Museum of Science and Industry, are some of the most sought after.

“[Miller] was the mass production master,” Glennon says. “He was like what Ford was to the automobile.... He marketed them by the millions. So they’re all over the place. Years ago, before eBay, they were really hard to come by.”

Despite its retro appeal, Mold-A-Rama is far from a dead art form. In fact, new designs are still being commissioned, at the rate of roughly two per year. For the past 25 years, Lois Mihok, an industrial model maker with 60 years of experience, has crafted numerous molds for Jones, including a bison, Oscar Mayer Weinermobile, and an Edison light bulb.

Mihok says Mold-A-Ramas are more complicated than some of her other projects because she has to ensure the plastic will easily separate from the cast once formed. Removing the figurine becomes more difficult if it includes an extremity—a tail or a leg, for example. But at the same time, designs with more detail and texture can counterintuitively be simpler to conceive because it’s easier to hide the mold line that connects the two sides.

Although the 83-year-old says she’s never seen a Mold-A-Rama machine in person, she is excited that people across generations appreciate her work.

“For some reason or another, everybody loves miniatures,” says Mihok. “For the kids to put money into a machine and press a button and have something come out like that, they have an interest in it because they feel like they made it.”

Jones isn’t the only Mold-A-Rama operator who continues the family business in plastic toy vending machines. Tim Striggow runs the Florida-based Replication Devices, which operates Mold-A-Matic (Jones has the Mold-A-Rama copyright) machines in the South and Midwest. Like many of the “handshake deals” in their businesses, Jones and Striggow divided the country into territories, with Mold-A-Rama machines currently in Illinois, Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota, and Texas, and Mold-A-Matic machines in Florida, Tennessee, Oklahoma, and Ohio. While the companies operate independently, Jones and Striggow send new molds to each other and regularly talk through challenges in maintaining the decades-old machines.

In the late 1960s, after visiting a state fair and realizing the machines’ business potential, Striggow’s grandfather Eldin Irwin first leased and later bought several from Automatic Retailers of America, which owned all of Mold-A-Rama until it divested in the early 1970s. Around that time, as a pre-teen, Striggow had begun helping monitor his grandfather’s collection. He remembers meeting Mold-A-Rama fans as he traveled to summer fairs with the machines. Some of those people came to the same events every year looking for the latest designs.

Striggow never thought the business would continue, even when his mom and stepdad took over in the 1990s. Now some of his contracts are over 30 years old, and he employs his son-in-law. He says he has the largest collection of machines—around 120—with about half in operation, including one at Jack White’s Third Man Records storefront in Nashville.

White saw a Mold-A-Rama when he visited Chicago in 2005 and wanted one for the Third Man Records Novelty Lounge. The Nashville machine produces a “cherry red” model of White’s 1964 Airline guitar. Third Man added a second machine at its Detroit location with a yellow replica of the label’s mobile Rolling Record Store.

“We like presenting people with these forgotten, cast-off processes and machines and giving them life,” says Third Man co-founder Ben Blackwell. “I imagine anyone who made these machines back in the day or was involved in their creation or maintenance would never expect that now—we’re talking the year 2018—they’re still working and people are still engaging with them. That’s beautiful. You can’t predict that.”

Despite Mold-A-Matic being somewhat of a competitor, Jones keeps a model of the Jack White guitar in his office display case, which also houses original Miller molds and the stick his dad used to mix melting plastic. Although he’s not opposed to modernizing his business, adding credit card slots to machines and staying open to unconventionally colored options like the Lincoln Park Zoo’s green gorilla, he credits Mold-A-Rama’s longevity to the old-school, vintage style.

“It’s a true form of American manufacturing,” he says. “All of the machines were made in America, made here in Chicago actually. There’s a niche that they maintain. I think it helps that we have never tried to change it. We leave it right where it’s at and pay honor to it and try to let it survive. It seems to be just doing that on its own at times.”

*Update 1/24: This post has been updated to clarify the difference in terminology between the aluminum mold inside the Mold-A-Rama and the plastic product it produces.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook