The Revolution Was Televised, Thanks to This 25-Pound Video Rig

In the 1970s, the Portapak gave a voice to outsiders and changed media forever.

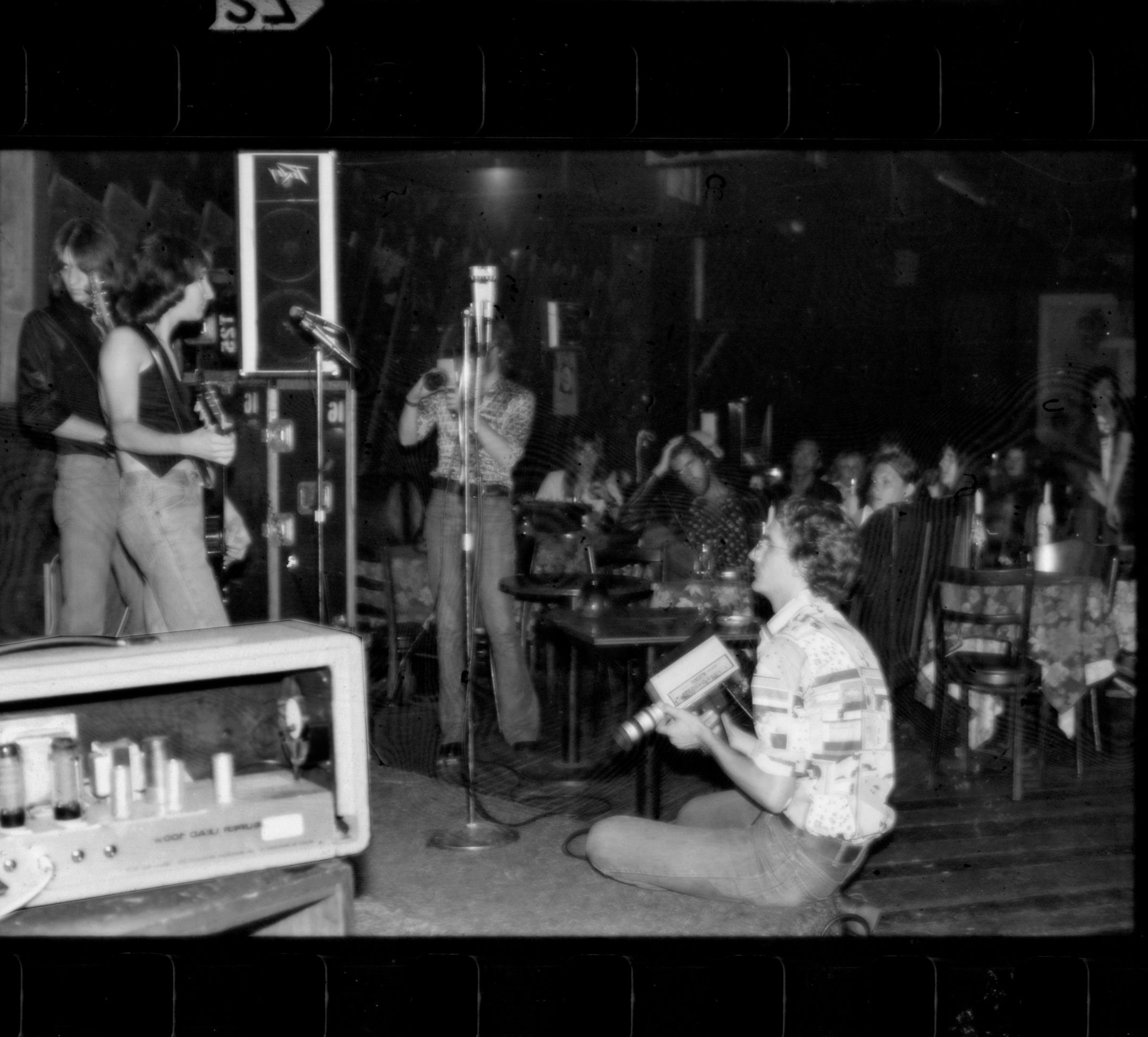

New York in 1975 was the kind of place punk-music-loving kids could really fall in love with. Patti Smith at Max’s. The Ramones at CBGB. A burgeoning culture was forming right before their eyes. There was art in the air. Raw energy, waiting to explode. This didn’t go without notice to a group of students and filmmakers working at Manhattan Cable Television’s public access department. This music-and-film-loving group knew that the punk scene was where they needed to be pointing their cameras.

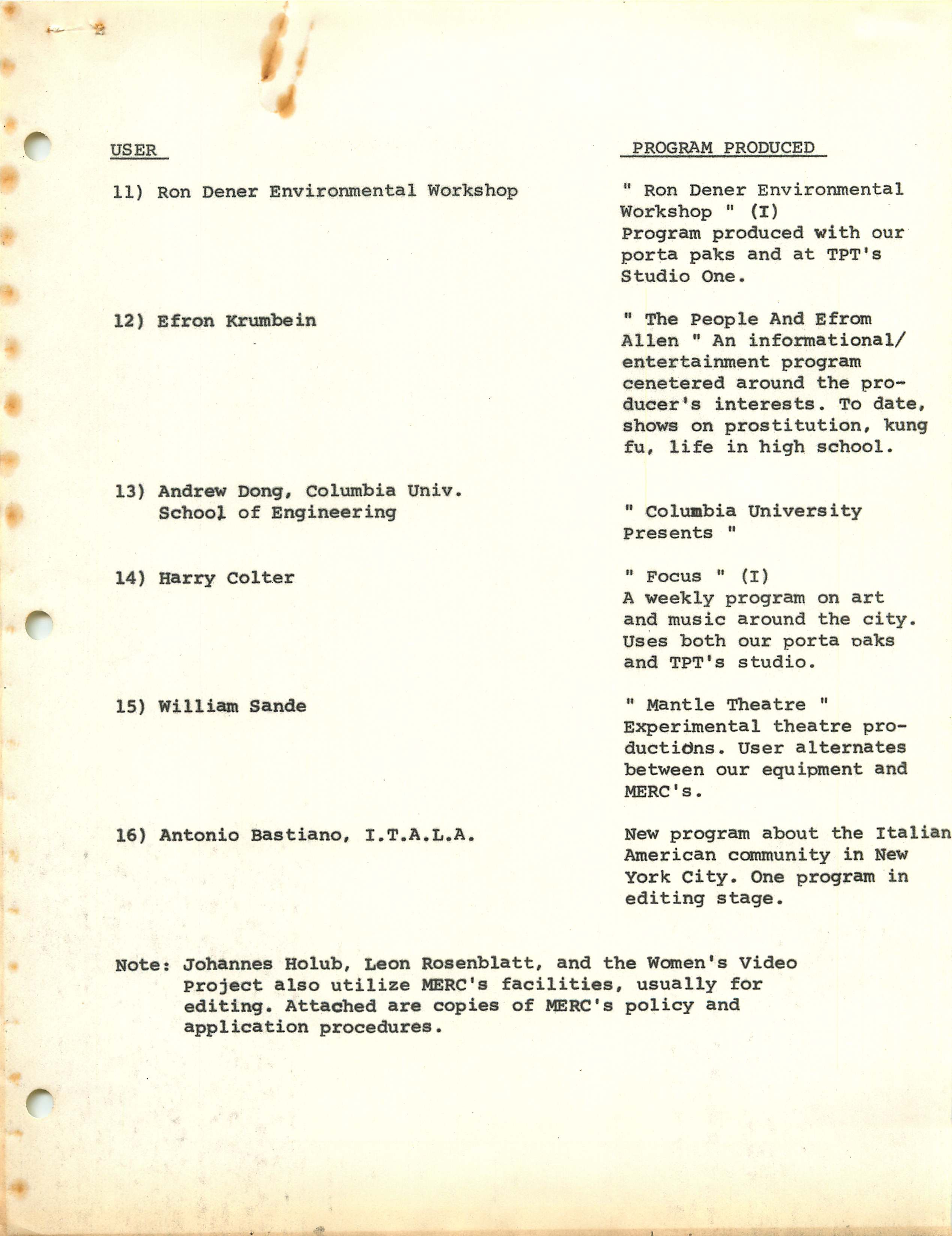

“We had all this equipment lying around,” says Patricia Ivers, a former intern in the department. “We [needed to] do something with it, and [this music] was so significant.” There was an unsigned band festival coming up at CBGB and the group talked Hilly Krystal, the club’s owner, into letting them bring their equipment in to record the bands. The group, as members of the video collective Metropolis Video, went on to capture early performances from some of punk’s and new wave’s biggest bands. This also put them in the middle of a growing movement in media-making, television, and technology.

The department was equipped with Manhattan Cable’s Portapaks—portable, handheld cameras and recorders that used videotape, rather than film—which let them shoot and edit all with one piece of equipment. Sony had introduced the camera in 1967, giving consumers access to portable video equipment for the very first time. “This was bleeding-edge technology,” Ivers recalls. Before the invention of the Portapak, merging images with sound was a much more involved process. As the media historian and curator Deirdre Boyle explains, “At that point sound and image were disconnected. Once the film was processed you had to sync the sound, but with video you had it all at once. It was immediate. You could shoot it and play it right back. The people you shot could see it right away. You couldn’t do that with film.”

Freed from the constraints of bulky tripods and heavy studio cameras, these new, lighter cameras also put the members of Metropolis Video close to their subjects, in a way that hadn’t been possible before. That first night with the Portapaks at CBGB, Metropolis filmed the Talking Heads, Blondie, and The Heartbreakers—a new band formed by ex-Television guitarist Richard Hell and ex–New York Dolls guitarist Johnny Thunders. All of them were unsigned and poised to change the landscape of popular music. “It was exhilarating,” Metropolis’s Steve Lawrence says. “We were liberated as artists, and we wouldn’t have been engaged in the same way with our heavier equipment.”

“You could see a person’s face as you shot. We kept eye contact,” says Tom Zafian, another Metropolis member. “We were really close to the musicians, trying to get a new, intimate feel. We were part of the whole thing.”

Metropolis Video, and other groups like them, were part of a much bigger change in media-making in general. Television production was no longer just in the hands of corporations—it belonged to the people. Students, activists, and radical new media-makers were pushing the boundaries of broadcasting, and the emerging portable video technology of the time was making it possible in a way it had never been before.

At 25 pounds (the camera plus the recorder) and priced at around $1,500, the Portapak was lighter and cheaper than anything available before it. This meant it was possible for small producers, such as public access operations, to own one or more of them. Though heavy by today’s standards, its offered a portability that was essential to capturing communities on the margins. Crucially, it also allowed for what had been impossible before: live shooting and editing, right on the scene. “This was battlefield recording,” Zafian says. “You had to concentrate, mix your ass off, and see what happened.” The cameras could be hooked up to portable switchers and monitors, so whoever was serving as director on a shoot could switch between cameras. The director could also fade in and out between shots and cameras to create the visual experience she wanted. This was the TV studio reborn in the wild.

Metropolis’s earliest recordings went back to Manhattan Cable and were shown as a three-part series, Rock From CBGB’s. (“Seen Saturday nights at midnight on Manhattan Cable’s Channel D,” announced a New York Times listing from 1975.) These portable cameras weren’t just making it possible to capture the rise of an underground music scene. They were something far bigger, Zafian explains. “Public access was for the people. It was the democratization of television.”

Still, it was a weird, outside medium, perfect for weirdos and outsiders.

The Portapak revolution meant that, during a tumultuous social and political time, those who were out of the mainstream—placed there by the established order, or proudly occupying the fringes—could have their voices heard on-air. “Everyone who cared was on the margins, you didn’t want to be mainstream.” Boyle says. “Most people picking up a Portapak had grown up watching network television, and [the Portapak] gave us the tools to make something uniquely our own, not tailored to the whim of the monolithic TV channels. Suddenly people had the tools to challenge TV on their own terms, showing what could be done on their own.” It also meant that video and activism became intertwined. John Hazard, another Metropolis member agrees, “There was this feeling, sort of like self-publishing, a sense of counterculture.”

These radical media-makers didn’t, and maybe couldn’t, find a home on more traditional stations. “[Traditional] TV considered it sub-par,” says member Michael Owen. “And the film people had no way to project it. It was ‘bastard tech,’ and not embraced.” In addition to broadcasting, Manhattan Cable also taught anyone who wanted to learn how to operate the equipment. Along with several other video collectives and organizations of the era, Manhattan Cable can be credited with changing the way people thought about TV and media in general. The New York video collectives Raindance and Videofreex were looking at video as a means of social change, and across the country, San Francisco’s Video Free America was advancing the field of video art. Portable video freed not just the means of production, but the means of broadcasting. “All of a sudden, you could make TV by yourself, says Zafian. “It was YouTube without the internet.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook