The Bumpy Business of Hauling Historical Sites to Safety

When trying to outrun erosion and sea-level rise is the best option.

You wouldn’t expect a 2,800-ton lighthouse to be light on its feet. But in July 1999, North Carolina’s historic Cape Hatteras Lighthouse tiptoed up the shore. The brick, black-and-white behemoth, which stands more than 200 feet tall, was too close to the crashing waves for comfort. And the problem wasn’t going to get better.

When the beacon was erected in 1870, it was 1,500 feet from the sea. Over the years, tides carved sand from one location and heaped it onto another, whittling down the shore around the lighthouse. By 1970, it was just 120 feet from the water. Experts cautioned that a storm surge could disturb the sand or the yellow-pine timbers of its foundation, causing the structure to buckle or even collapse. Assuming that sea-level rise didn’t accelerate beyond its 1988 pace, a panel of experts from the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) forecast that the shore would retreat by a minimum of 157 feet by 2018. So, in 1988, they set out to plot a defense strategy.

There are a number of ways to stave off erosion and advancing water. You can fight, by replenishing dunes, planting dense thickets of beach grass, or building a barricade of cement or sandbags. Or you can flee, by giving in, cutting your losses, and coming to terms with sacrifice. The NAS team considered these options, then cast them aside, in part to maintain sight lines, scenic beauty, and access for visitors.

But just plucking the structure up and moving it to safety? That sounded more promising. And that’s how it came to pass that the hefty sentinel—and a host of accompanying historic structures—migrated inland. To make the move, engineers placed hydraulic jacks under the lighthouse and heaved it onto steel mats. As it rolled along on beams and dollies, 60 automated sensors tracked tilt and vibration, and a weather station kept tabs on wind and temperature. At its new home, 1,600 feet from the ocean, the lighthouse was planted atop a parfait of stabilizing materials: nearly two feet of rock, five feet of brick, and a concrete slab with a steel backbone.

Today, erosion imperils tens of thousands of archaeological sites in the United States, most notably in the Southeast. A new paper, published last week in PLOS One, outlines the scope of the threat: A one-meter rise in sea level could swamp 13,000 documented historic and archaeological sites across the region (and an untold number still flying under the radar). If sea levels rise by five meters, more than 32,000 sites would be destroyed. The paper summarizes a mind-boggling heap of data, available through the Digital Index of North American Archaeology, a growing database that layers a site’s location with its elevation and vulnerability. (Precise coordinates are withheld, partly to deter would-be looters.) “Given the large numbers of cultural resources threatened by sea-level rise, planning possible protection and mitigation strategies should proceed with an increased sense of urgency,” the authors write.

How many of these historic assets might benefit from a move inland, like the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse’s? The National Park Service’s coastal heritage preservation guidelines describe a few relocation scenarios, including lugging buildings to new foundations, scooping museum collections out of harm’s way, and allowing some natural elements to shift location on their own. There are cultural considerations to be mindful of as well: Disinterring and moving a Native American burial ground is tantamount to desecration, says Paul Backhouse, the director of the Ah-Tah-Thi-Ki Museum and Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Seminole Tribe of Florida. More broadly, archaeologists would prefer not to intrude upon sites wherever possible. The Florida Public Archaeology Network takes this approach, and enlists both professionals and a troop of more than 200 volunteers to monitor at-risk sites across the state. In the case of the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse, some critics argued that moving the structure—even somewhere nearby—blunted its history. “They don’t want to see a lighthouse that’s been cut down and moved half a mile,” a local mechanic told the WRAL TV station at the time. “History took place on that site.”

Plus, relocation isn’t cheap. The NAS budget, for instance, estimated that the lighthouse relocation would cost $4.6 million in 1988 dollars. The report authors argue that it was worth it, because this intervention “would provide the most reliable, cost-effective, and prudent long-term protection for the lighthouse by allowing it to be moved away from the approaching sea as the need arises.”

Relocation is “a pretty monumental engineering challenge,” says David Anderson, a professor of anthropology at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, and coauthor of the new study. But it’s clearly not without precedent, and engineers have gotten rather good at it. “I imagine people could move just about anything,” says Anderson.

The NAS team made a similar argument in their lighthouse-moving campaign. “Despite the apparent difficulty of moving a large brick structure, the operation entails minimal risk,” the committee wrote. “Many structures larger and older than the Cape Hatteras Lighthouse have been moved successfully.” That’s an understatement. Decades earlier, a UNESCO-led coalition of 50 countries pitched in to relocate Abu Simbel, an ancient temple carved directly into an Egyptian hillside.

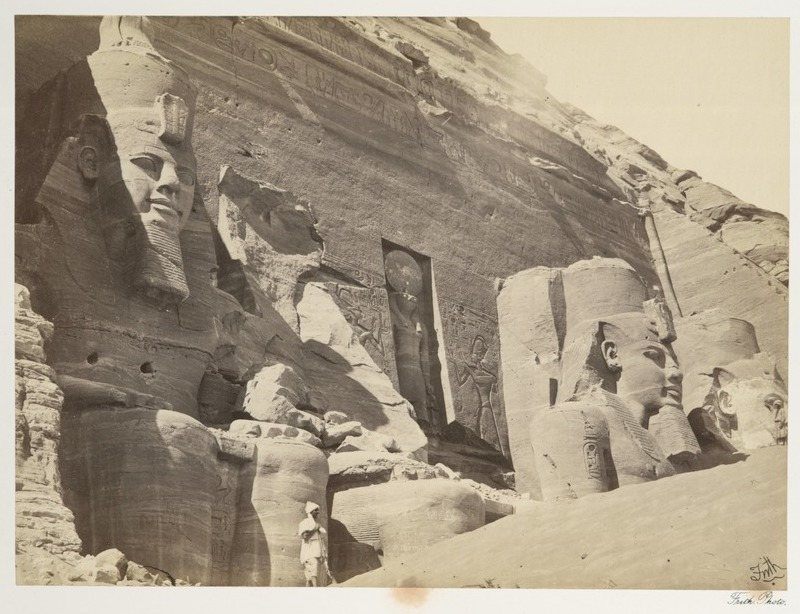

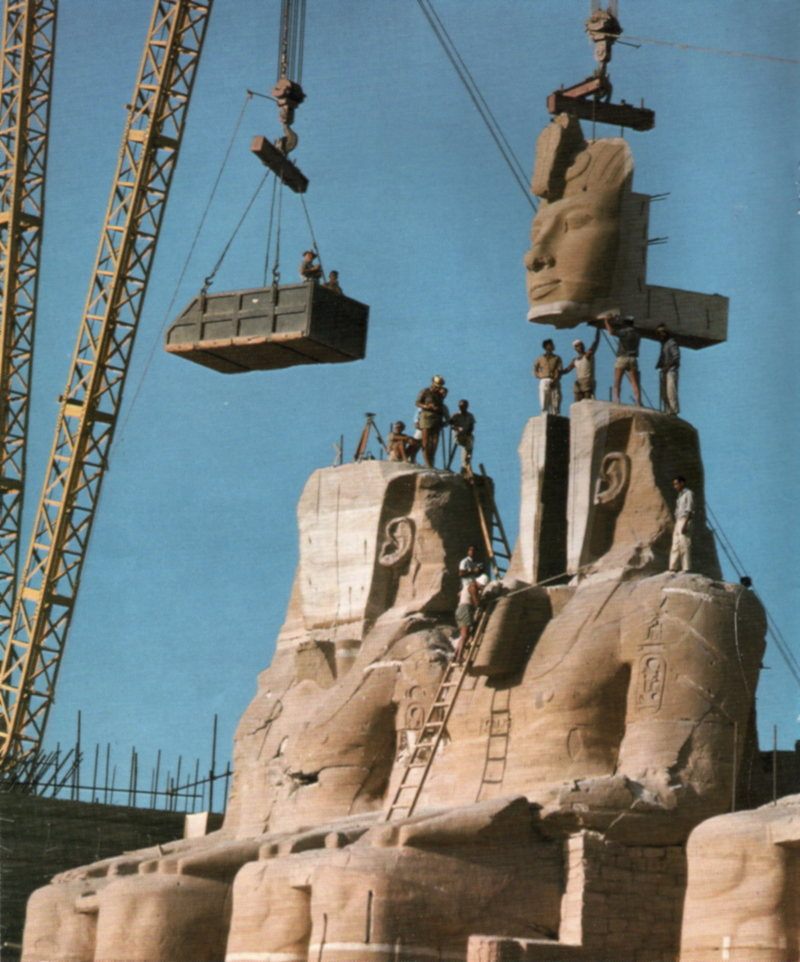

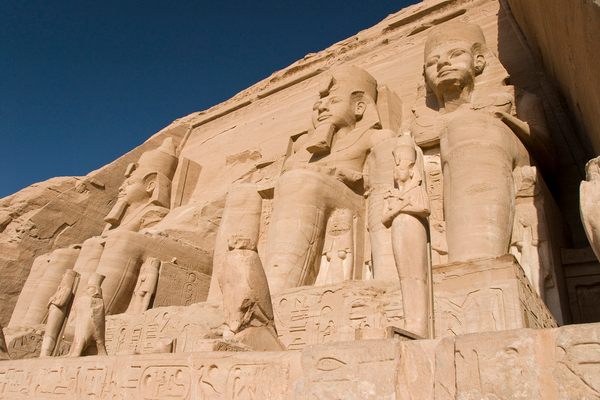

Since 1244 B.C., sandstone statues of the Pharaoh Ramesses II had lorded over the desert from a height of 60 feet. In the mid-1960s, to harness the Nile for electricity and tame the river’s notorious floods, the Egyptian government set out to construct the Aswan High Dam. The new structure would raise the water level in Lake Nasser, and the downstream plain, studded with ancient monuments, would be subject to collateral damage.

Archival photos capture their efforts: ladders, ropes, and thick scaffolding, and diminutive figures in the shadows of the statues’ colossal knees, toes, and chins. Crews used handsaws and a few powertools, but no explosives, to carve the figures into 20-ton blocks. Cranes then swung the massive faces across the hilly landscape, as scores of workers waited beneath to lower them into waiting trucks. The $40 million project relocated Abu Simbel more than 213 feet higher than the previous site, and 650 feet from the river.

More recent relocation efforts have unfolded on U.S. shores, but they’re still rare. Coastal erosion and sea-level rise have only started flickering on cultural heritage officers’ radars in the past few years, partly in response to the destruction caused by Hurricane Sandy, says Shantia Anderheggen, Director of Preservation at the Newport Restoration Foundation (NRF) in Rhode Island. The United Kingdom has been planning for this risk for much longer, she says: “We’re aching for case studies, because we just don’t have a ton.” The NRF’s recent “Keeping History Above Water” conference, Anderheggen says, was partly an attempt “to catch us up with the rest of the world, frankly.”

Over the course of three days in the summer of 2015, another historic lighthouse, the Gay Head Light, dating back to 1844, was moved 129 feet back from the edge of a Martha’s Vineyard cliff. Prior to the move, it “was one or two big storms from falling into the water,” says Kelsey Mullen, the Public Programs Manager at NRF. Proponents believe the move will keep the structure safe for at least 150 years. Meanwhile, in San Francisco, a plan is underway to crank Pier 70, which supported maritime industry since the 1880s, above the water line. Infill would be used raise it up 10 feet.

Lifting and shifting historic structures from one place to another is challenging, but at least it’s clear and easily understandable. But it’s much trickier to consider what to do about buried archaeological sites—sunk in the very ground that is being eaten by the sea.

Erosion is a prime concern in coastal Louisiana, where United States Geological Survey data indicate that 1,883 square miles of land were lost between 1932 and 2010. “If this loss were to occur at a constant rate,” the government researchers wrote in a 2011 paper, “it would equate to Louisiana losing an area the size of one football field per hour.” Already, places that were “on land 100 years ago are several hundred feet out into the water,” threatening to hide the traces of prehistoric communities and the early fishing industry, says Brian Ostahowski, president of the Louisiana Archaeological Society. Storm surges now loose submerged artifacts, jumbled together, sometimes without the original context archaeologists need to make sense of them, Ostahowski says. “This is such a ‘womp, womp’ Charlie Brown thing,” he adds. “Every time I talk about it, it’s so frickin’ depressing. It always ends on this down note; it’s such a drag.”

While Ostahowski recognizes that you can’t excavate everything, particularly Native American sites, he campaigns for unearthing places threatened by the ocean when it’s urgent and feasible. He likens the process to triage.

Being far from the ocean isn’t necessarily protective these days either. While extreme storms will obviously lash beachfront sites, the authors of the PLOS One report note that places farther inland are vulnerable to river floods or spillover from swamps or ponds—and less likely to elicit the same kind of concern. They could be submerged quietly and invisibly. The Farnsworth House, a glass pavilion designed by the architect Mies van der Rohe, was recently outfitted with permanent hydraulic lifts to raise it above floodwaters from the Fox River in Plano, Illinois. In Washington, D.C., the Lincoln Memorial sits just 10 feet above sea level, and the authors of the PLOS One report flag it as another potential relocation candidate.

For all these reasons, Anderson wants to sound a blaring alarm. “Climate change isn’t the future,” he says. “It’s always. It’s happening right now.” One option is trying our best to outrun it.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook