The Centuries-Old Shrine Where Indians Pray for U.S. Visas

It has a decent track record.

Statues at the front gate of the temple depict the unearthing of the god’s image from the anthill. (Photo: Tim Williams)

Every year, thousands of pilgrims travel to a small temple in the Indian village of Chilkur to ask for United States visas.

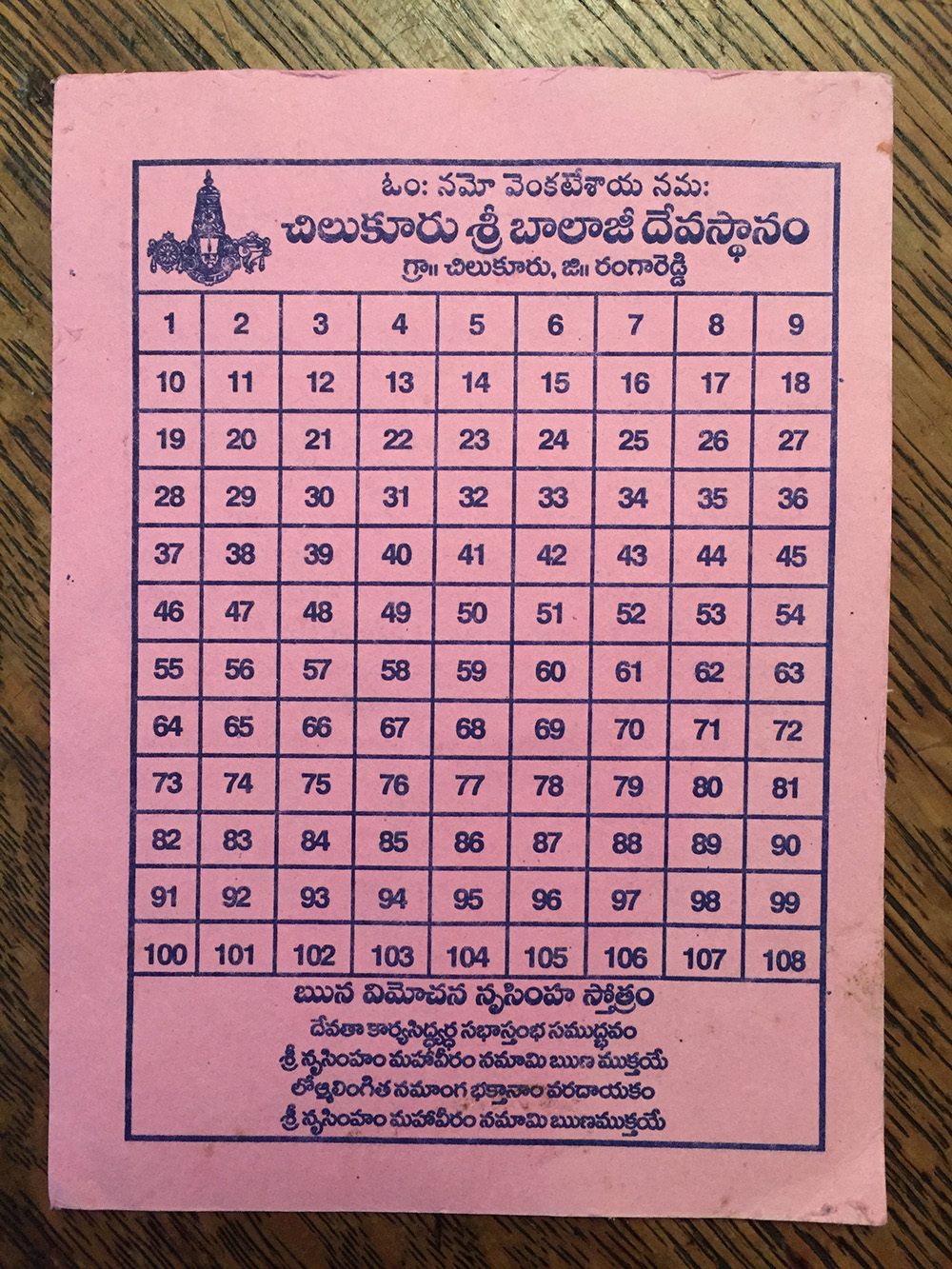

In a shady courtyard, they circumambulate a shrine 11 times. Those who receive their visas come back and make 108 more circuits, marking each lap on a pink chit and leaving bundles of holy basil in front of the god’s image.

It’s not just visas: visitors to the temple also ask for spouses, children, property, and even government postings—according to a priest there, a minister came and made 108 grateful circuits shortly after getting his job. But immigration documents have become the temple’s signature wish. Around the shrine to Balaji—an incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu—tradition mixes with globalization, and the bureaucratic and the divine intersect.

At first glance, Chilkur is an unlikely place for a booming Vishnu shrine with a national reputation. It is an unremarkable agricultural village on the western edge of Hyderabad, a city with a significant Muslim minority. The area is better known for its mosques than its Hindu temples.

The gate to the temple. (Photo: Tim Williams)

But Hyderabad is also an emerging hub of India’s tech industry. Dell, Microsoft, Apple, Google, and Amazon all have major offices there. Hyderabad is a college town, too, with a number of big engineering schools. A 2014 Brookings Institution report found that the city sends more people to study in the United States than Delhi and Mumbai combined, and more than almost any other city in the world.

In other words, it’s a hotbed of ambitious young people who may be looking for F-1 (student) and H-1B (skilled employment) visas to the United States. And there, right in the neighborhood, sits a temple with a reputation for granting wishes.

The whole phenomenon—wishes, visas, crowds of pilgrims—is fairly new. According to legend, the Chilkur Balaji temple was originally founded in order to help someone avoid making a long journey.

Around 500 years ago, a local man grew too old to make his annual pilgrimage to the temple city of Tirupati, some 400 miles away. One day when the man, feeling depressed, fell asleep, the god appeared to him in a dream and said that he didn’t need to go all the way to Tirupati to worship. The deity then directed him to an anthill in the jungle.

A statue at the Chilkur Balaji Temple. (Photo: Ritu Manoj Jethani/shutterstock.com)

When the man and other villagers went into the forest and began digging up the anthill, their tools struck a hard object, and the mound began to bleed. A voice told them to pour milk over the hill, and the image of Vishnu that now sits in the Chilkur Balaji temple emerged from the mound.

Today, the temple is surrounded by avenues of stalls selling toys, candy, snacks, and divine images, as well as flowers, coconuts, and strongly scented tulsi leaves for ritual offerings. On Saturdays, thousands of people come to Chilkur, forming a queue that stretches deep into the village. When I visited the temple earlier this year, it was a quiet weekday morning. Inside, approximately 200 worshippers walked around a courtyard that’s roughly the size of two basketball courts. In the middle sits the small building that houses the inner sanctum of the temple.

A full circumambulation takes a bit less than two minutes; the 108 circuits of a successful visa-holder can take hours. Entering the circuit feels like jumping into a quick-moving creek; all of a sudden there’s motion, and when you finally reorient yourself, you’re already downstream, bobbing along with the flow.

Sitting outside the inner sanctum, holding a microphone, a priest spoke to the pilgrims in Telugu. Occasionally he would chant a Sanskrit mantra or shout “Govinda!”—a name for Vishnu—to which the worshippers would respond with a loud “GOVINDA!” Many of them looked to be in their 20s. Some were elderly. A few seemed tired. One young man was wearing a t-shirt that read “I ♥ Math.”

A pink chit is used to mark each lap around the temple. (Photo: Michael Schulson)

When I went up to ask the priest—whose name is Rangarajan—if he had time for an interview, he agreed. Then he decided to multitask. Rangarajan told the pilgrims that a reporter was going to interview him, and that, in the interest of education, we would conduct the interview using the microphone, in the middle of the 200 circling worshippers, so that those among them who spoke English could learn a little bit more about the temple’s history.

I hadn’t expected an audience. Rangarajan invited me to sit down. A cord was wrapped around his bare torso like a sash, and he had a tapering U-shape—characteristic of Vishnu worship—painted on his forehead, arms, and chest in yellow and white strokes. Rangarajan explained that the temple, unlike most Hindu shrines in India, does not accept cash donations or fees, exempting it from government regulation—and quite a lot of potential income. He spoke passionately about the values of a pluralistic society. He told me that two Catholics nuns had recently visited and said that they were “finding a divine experience here.”

Then he explained how the temple had come to attract so many hopeful worshippers. The first wish was for water. In the early 1980s, Rangarajan’s uncle Gopalakrishna, another priest at the temple, decided to drill a borewell. While the well-diggers drilled into the earth, he began to circle the Balaji shrine, asking for success.

“And guess what, it started working! The moment he walked 11 times around the temple, the water was found,” Rangarajan said. Gopalakrishna continued to walk, and the well continued to pump out fresh water. On the 108th lap, though the pump sputtered to a halt.

Lining up at the temple. (Photo: Ritu Manoj Jethani/shutterstock.com)

But when Gopalakrishna left the temple, it kicked back on. “So this is the indication from the god, enough of your rounds,” Rangarajan explained.

Word about the incident got out, thanks in part to Gopalakrishna himself. “He did not keep quiet,” Rangarajan said. “He started telling people, so they started knowing.” People began visiting to ask for favors from Balaji, making 11 circuits around the shrine to ask for help, and 108 to give thanks.

And then, around the mid-1990s, students from the engineering colleges started showing up asking for visas.

When I asked how often people come specifically for visas, Rangarajan switched to Telugu and asked the circling worshippers to indicate if they were there because of a visa request. Nearly half of the people raised their hands. A young man passing by even held up his passport, showing the H-1B visa inside.

Later, I caught up with him in his 44th lap, and he paused for a quick conversation. Reddaiah Kovuru is a software engineer from the neighboring state of Andhra Pradesh (until the state was divided in 2014, Chilkur was part of Andhra Pradesh).

Looking in through the gate. (Photo: Tim Williams)

He first heard about the temple from friends in Hyderabad, and he came in 2009 to ask for a visa. “I wanted to have the global exposure, so that’s the reason I wish to have a U.S. visa. So I prayed here.”

Kovuru’s first application, for a student visa, was denied. He went to work in Bangalore instead, and he recently received a one-year H-1B visa after sitting through a 45 minute-long interview with an American official in Chennai. “I had so many struggles to get this,” he said, showing me the crisp document in his passport.

I asked Kovuru why Vishnu helps people with visas and other requests. The question seemed to make him uncomfortable. “I mean, our forefathers believed, and we are also following the same,” he said. He had traveled all the way from Bangalore to Hyderabad—some 350 miles—in order to fulfill his promise to the god.

As anyone who has ever applied for a U.S. visa can probably tell you, the process is intimidating and opaque. In the age of modern states and closed borders, bureaucracy can come to feel like a peculiarly capricious supernatural power: vast, inscrutable, and extraordinarily powerful. In the face of this new force, it might be wise to enlist some more traditional help.

For Kovuru, Chilkur was among his final stops in India. Just a few days later he would board a flight to Newark, and then begin his new job in New Jersey. He told me he was excited, not nervous, about what lay ahead. Then he headed back into the flow, with 64 laps and a few thousand miles to go.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook