The Incredible Chevalier d’Eon, Who Left France as a Male Spy and Returned as a Christian Woman

Celebrity, scandal, tell-all books, palace intrigue, political protest and more.

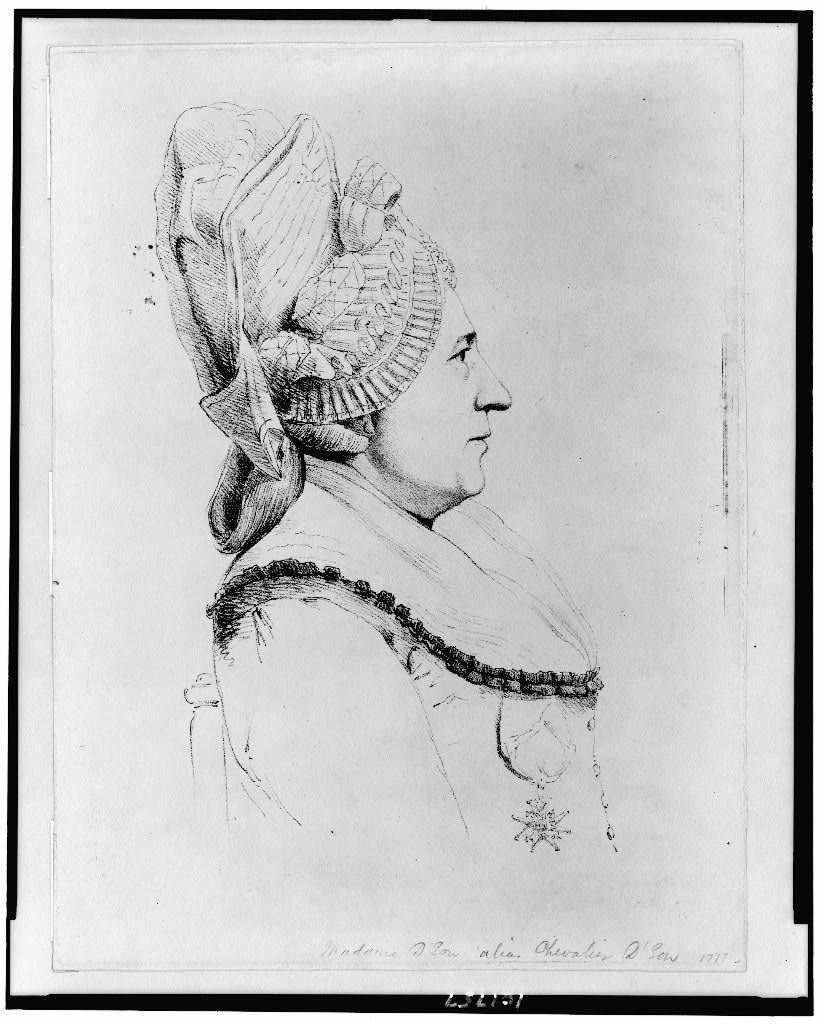

A profile view of the Le Chevalier d’Éon. (Photo: Lyon, Bibliothèque municipale/Public Domain)

When the Chevalier d’Eon left France in 1762, it was as a diplomat, a spy in the French king’s service, a Dragoon captain, and a man. When he returned in July 1777, at the age of 49, it was as a celebrity, a writer, an intellectual, and a woman—according to a declaration by the government of France.

What happened? And why?

The answer to those questions is complex, obscured by layers of bad biography, speculation and rumor, and shifting gender and psychological politics in the years since, as well as d’Eon’s own attempts to reframe his story in a way that would make sense to his contemporary society. (Note: In consultation with d’Eon’s biographer, I have decided to use the male pronoun when talking about d’Eon before the gender shift and the female pronoun after.) Professor Gary Kates of Pomona College is one of the first modern academics to look closely at the life—or lives—of the Chevalier d’Eon, in his comprehensive biography Monsieur d’Eon Is a Woman. Kates had access to d’Eon’s personal papers, a treasure trove of manuscripts, diaries, financial records, documents, and letters housed at the University of Leeds, and his work is widely considered the best place to start when considering d’Eon.

The story Kates tells is a complex narrative, involving Ancien Regime intrigue, secret spy rings, political necessity, burgeoning celebrity culture, and nascent feminism. The meaning of d’Eon’s transformation has been dissected for centuries; feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft praised d’Eon in their lifetime and contemporary trans groups have named themselves in d’Eon’s honor.

Even so, Kates cautions that the history of this fascinating figure is far from complete. “I don’t think I’ve written the definitive book on d’Eon,” he says. How could he? This is a person who lived enough for three lifetimes.

The King’s Secret

Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée d’Éon de Beaumont was born October 5, 1728, to a minor aristocratic family in Burgundy; despite later claims, there was no hint of anything unusual about his birth and he was declared a boy. After a largely uneventful adolescence and completing his studies in Paris, d’Eon’s family’s connections secured him a place in civil service. He steadily climbed the ranks until, in 1756, d’Eon became secretary to the French ambassador to Russia.

This traditional role, however, was just a cover: D’Eon was also tapped for another royal service—le Secret du Roi, or “King’s Secret”. The Secret was a network of spies and diplomatic agents established by Louis XV in the 1740s with the aim of putting his cousin, the Prince de Conti, on the Polish throne and turning the country into a French satellite. The Secret was so secret, it was hidden from and sometimes acted against the official French foreign ministry. D’Eon was charged with fostering good relations with the Russian court of the Empress Elizabeth and getting her behind installing Conti in Poland, as well as promoting France’s interests generally. Though d’Eon was competent, by all accounts hardworking, charming, and clever, the geopolitical reality was grim: That same year, France had entered what would become the Seven Years War with Britain.

The war did not go well for France and by March 1762, Louis XV called for peace talks to begin. In August 1762, d’Eon, who had left Russia for a stint as a Dragoon in the French Army, was appointed secretary to the French ambassador who was then negotiating the peace with Britain; he was also admitted to the prestigious royal and military Order of Saint Louis, a huge honor for a man only 35 at the time, and allowed to call himself “Chevalier”, the equivalent of “Sir”. When the peace treaty was signed in February 1763, France found itself stripped of its colonies in North America, saddled with enormous debts, and desperate for revenge. So the Secret regrouped with a new purpose: Invade Britain. In April 1763, d’Eon was named minister plenipotentiary, with the status of ambassador, to the British court—an excellent cover for directing a survey of the English coast to find a good place to mount an invasion and cultivating members of Britain’s opposition party in Parliament.

Le Chevalier D’Éon. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/CC BY 4.0)

Le Chevalier D’Éon. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/CC BY 4.0)

Things seemed to be ticking along for d’Eon’s career, but within months, it would all crumble. For starters, he had expensive tastes, much to the frustration of his cash-strapped government, and was reprimanded for importing too much wine. And he wasn’t really the ambassador. The real ambassador, the Comte de Guerchy, was a man with little diplomatic experience and not well-liked or particularly competent; he was expected to arrive within the year, and d’Eon would be demoted to secretary. The awkwardness was compounded by the fact that though d’Eon was under Guerchy in his above-board ministerial position, he was above and sometimes at odds with Guerchy in his work in the Secret. The situation, d’Eon claimed, was untenable and he let his superiors know that in a series of increasingly angry letters.

On October 4, 1763, just six months after he’d been given the job, d’Eon was fired for his insolent behavior. He had until the 19th to come home for chastising.

D’Eon wasn’t going. He had real reason to fear that he was headed for the Bastille – other inconvenient noblemen had disappeared for less – however, d’Eon also knew that his position in the Secret afforded him a measure of protection. Louis XV ordered d’Eon be extradited back to France, but the British foreign minister refused, declaring that d’Eon was free to stay in Britain as a private citizen. D’Eon wasn’t out of danger yet—the French Foreign Ministry made several attempts to kidnap and arrest him. In retaliation, d’Eon intimated to his superiors in the Secret that he would tell everything if he wasn’t vindicated. And in March 1764, he fired a warning shot: He published a scandalous book, the first of several promised volumes, of all his diplomatic correspondence since being named minister plenipotentiary.

The effect was staggering. D’Eon went from a somewhat minor figure on the European political stage to the central character for a short time, talked about not only by heads of state but by newspapers, in cafes, even in aristocratic households as well: Kates includes a contemporary letter from a 16-year-old girl to her friend in which she dishes about d’Eon’s “treasonous impudence”.

King Louis XV, who established le Secret du Roi in the 1740s. (Photo: Palace of Versailles/Public Domain)

It was shocking, it was libelous, but it worked. In some sense, d’Eon had thrown himself not on the mercy of the British government, but the British people, which gave him a kind of celebrity protection. And the fact that he had made himself an open enemy of the French Foreign Ministry made him even more useful as a spy, allowing him to entrench more deeply in British society. Louis XV quietly gave D’Eon a lifelong pension of 12,000 livres annually, in exchange for reports about British politics and handing over the incriminating documents about the Secret he possessed. D’Eon’s next volumes in his tell-all never appeared, however, and he was forbidden from returning to France. He spent the next decade in exile in London, still in service to his King.

But when Louis XV died in 1774, his son, the ill-fated Louis XVI, wanted the Secret eliminated. He saw no utility in having effectively two foreign policies, one secret, and, moreover, he no longer wanted to invade Britain. So d’Eon was again a problem.

Enter Pierre Beaumarchais, playwright and representative of the French government. In 1775, Beaumarchais approached d’Eon to negotiate his return to France and, crucially, the return of any documents he possessed pursuant to his spy work. After several months of discussion, d’Eon signed The Transaction, as the agreement was called: He would give up all papers and return to France as soon as possible. The king would pay some of his substantial debts and his pension, and he would publicly recognize d’Eon as a woman.

‘All the World Says It’

The only thing that made the plan at all plausible was the fact that a lot of people, including the French government, already thought d’Eon was secretly a woman. As early as 1770, rumors began circulating in Britain and France that the Chevalier was actually a Chevalière, and once they started, they didn’t stop. One French aristocrat wrote to a friend, “All the world says it. Final incontestable proof!” The groundswell of gossip was enough that in 1771, London bookmakers started taking bets on his gender—3:2 odds that he was a woman, at first, before sinking to even money. The bizarre public debate made d’Eon’s life difficult; he couldn’t leave the house without armed guards, owing to the many people who wanted to see him naked, yet his understandable refusal to publicly reveal his gender prolonged the debate for years.

But there may have been more to his refusal than simple pride. In May 1772, a French secretary in the service of the Secret allegedly came to London to investigate the claim that d’Eon was a woman; he left in June, fully convinced that d’Eon was indeed female because that’s what d’Eon told him. From that point on, Kates wrote, the French government took it as fact that d’Eon was a woman. Kates believed that d’Eon planted the rumors himself, so that when Beaumarchais came calling in 1775, d’Eon was armed with a fictional narrative that he’d been born female but forced into the role of a son by a tyrannical father. This would have enabled him to retire from the Secret and return to France, as Kates suggested, a “heroine who had dressed up as a man in order to perform patriotic acts for Louis XV” in the eyes of the public, rather than as a “trickster”.

Nicholas Pocock’s painting The Battle of Quiberon Bay, during the Seven Years’ War between France and Britain. (Photo: National Maritime Museum/Public Domain)

Strangely, the scheme worked, although it would be another 18 months of squabbling with Beaumarchais and others before d’Eon would finally leave England, but in July 1777 he did. By then, most of Europe knew d’Eon’s story, or at least the version d’Eon wanted everyone to know: Born female, d’Eon was raised male by a father who wanted a son; he excelled as a diplomat and soldier; and was now coerced by the new king and propriety to adopt the appearance of his birth gender. As a condition of the Transaction, d’Eon was meant to return to France in women’s dress, but d’Eon was still wearing his Dragoon captain’s uniform, as much a symbol of his political power as gender, when he stepped off the boat. It took several months and a royal decree, but he was eventually coaxed out of it. He was handed over to Rose Bertin, famous clothing director to Marie Antionette, in whom he supposedly confided, “Truthfully, Mademoiselle, I do not yet know what I need…. I only know that it is more difficult to equip a lady than a company of Dragoons from head to foot.”

On November 21, 1777, Mademoiselle la Chevaliere d’Eon was formally presented at the court at Versailles, “reborn” after a four-hour toilette that included powdered hair, an elaborate dress and make-up. Contemporary reports nastily remarked that d’Eon was not an attractive woman: “She had nothing of our sex but the petticoats and the curls which suited her horribly,” declared one female courtier.

A fencing match featuring Mademoiselle la Chevaliere d’Eon at Carlton House in London, 1787. (Photo: Royal Collection/Public Domain)

After a period of adjustment, d’Eon appeared to embrace womanhood and her persona as an “Amazon” woman, although contemporary reports suggest that she never really comported herself quite in the style of other aristocratic women. It didn’t matter: Most of society accepted her story as fact and hailed her as a heroine in the mold of Joan of Arc. But the reality of life as a woman was also disappointing, and her political, patriotic voice was essentially muted. When France joined the American War of Independence in 1778, d’Eon petitioned the government to allow her to wear her Dragoon captain’s uniform once again, which she believed would enable her to go to war for France. Far from being moved, the government pressured her to enter a convent; others at Versailles, where she was now living, told her that the only way she could have any political influence was through marriage. When d’Eon continued to demand the government allow her to go to war, she was arrested and thrown into a dungeon beneath the Chateau of Dijon. She was released after 19 days and the promise that she would stop asking. Every political effort d’Eon made from then on would be immediately quashed by the French government, who eventually forced her into retirement on her family estate in rural Tonnerre.

Last Days in England

In 1785, she moved back to England, ostensibly to settle some debts but in reality, seeking the freedom from monarchic despotism that Britain seemed to enjoy; she was welcomed in society as a heroine. But when the French Revolution began in 1789, d’Eon’s annual pension was suspended, and she found herself broke. A sale of her famous collection of books couldn’t cover her debts and by 1791, d’Eon, now in her 60s, resorted to putting on fencing exhibitions for money, styling herself as a kind of swordswoman-warrior. Though lacking money, she still enjoyed a modicum of celebrity: In 1792, her portrait was painted by Thomas Stewart, with d’Eon wore a full cockade hat, in support of the French Revolution, and a dusting of stubble on her cheeks.

Mademoiselle la Chevaliere d’Eon. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-101757)

Mademoiselle la Chevaliere d’Eon. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-USZ62-101757)

The portrait, now housed at the National Portrait Gallery in London, was painted not long after d’Eon offered to lead an army of women for the fledgling French National Assembly. Her sword-fighting career lasted until 1796, when she was badly injured during a tournament and was forced to retire. Not long after, she was driven by poverty to share a flat with another elderly woman, a widow by the name of Mrs. Cole. She became a virtual shut-in, often too ill to leave her bed, and saw very few people.

She died May 21, 1810, at the age of 81. And then, Mrs. Cole made a startling discovery when she went to dress her friend’s body for burial: The woman who’d become a man to serve her king was biologically male. D’Eon’s obituary a few days later described her as a “political character” most remembered for her “questionable gender”, which, the papers said, could now be reported as definitely male. Hardly what d’Eon would have wanted.

A view of London and the Thames, 1794. (Photo: Public Domain)

The facts of d’Eon’s life are confusing, as are her real motivations for becoming a woman in the public and private eye. She left behind some 2,000 pages of unpublished manuscripts, including drafts of her autobiography, some of which was outright fiction and shed only partial light on why she did what she did. Viewing her decision with a 21st century lens, however, is almost certainly inappropriate: She is not exactly the 18th century Caitlyn Jenner, nor is she, “Britain’s first openly transvestite male”, as National Portrait Gallery curator Lucy Peltz told The Guardian in 2013.

“I see d’Eon’s gender transformation as a mid-life crisis which has very much to do with a reaction to the hyper-masculinity of diplomacy and politics of the Old Regime,” explained Kates, who said that d’Eon had come to see political life itself, backbiting and detestable, as the cause of her misfortunes. During the period after she was disowned by the French Foreign Ministry, d’Eon began collecting books on famous, virtuous women throughout history and early feminist thought, eventually amassing one of the largest collections of feminist writing in Europe; women, d’Eon came to believe, were more decent than men. “I think it’s at that point in his life that living as a woman comes to him as a way to transform himself morally and away to escape this hyper-masculine box he found himself in,” says Kates.

Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, playwright, pictured in 1755. (Photo: Institution:Comédie-Française/Public Domain)

Kates also sees d’Eon’s transition as a moral choice propelled by her re-found, fervent Christian faith; D’Eon himself referred to his transition as a “conversion from bad boy to good girl”. “[D’Eon] believes in two things: One is that whether we live as a man or a woman is a choice that all of us have and that women in the 18th century are living lives that are morally superior to men, and therefore we should choose, we men should choose to live as women,” explains Kates. In the context of her faith, said Kates, “It is the Christianity that empowers him to cross the gender barrier.”

That d’Eon had a choice at all Kates sees as emblematic of the progression of “bourgeois individualism”, as people with the means were increasingly able to decide against set roles and modes of behavior to do what fulfilled them. “This is obvious in the sense of occupations… Our occupations just followed us and we didn’t have any choice, but somewhere in the early modern world, we realized that we ought to have choice,” said Kates. “In that way, we’re just extending this to gender.”

Womanhood as Survival

Not all scholars accept that view of a revolutionary d’Eon. Dr. Simon Burrows, historian of the Enlightenment at Western Sydney University, is the editor of a collection of essays on d’Eon and has explored the story in the context of burgeoning celebrity culture. Though Kates asserts that d’Eon was in charge of his own destiny, Burrows doesn’t believe that d’Eon planted the rumors that she was actually a woman to furnish her later escape plan; he says there is evidence to suggest that d’Eon disguised herself as a woman in the 1760s to evade the French Foreign Ministry, and that it’s possible the rumors stemmed from those incidents. Burrows does, however, think it’s very possible that d’Eon didn’t dispel the rumors because he was accepting payment from betting houses to keep his gender a mystery.

Burrows says that d’Eon was in a tight spot when Beaumarchais approached her—she’d long been living beyond her means and the French government rarely paid on time. “D’Eon really has little option but to agree, but it also has advantages for him…. He needs money, doesn’t he? And in Britain there’s risk he’ll be locked up as a debtor, so he does it for his own safety,” said Burrows. “I think Beaumarchais out-maneuvers him at a time when he really wants to go back to France.”

Mademoiselle de Beaumont or The Chevalier D’Eon. (Photo: Library of Congress/LC-DIG-ds-03347)

The d’Eon that Burrows describes is more reactive, less considered and more survivalist. It could easily have been Beaumarchais’s idea to allow d’Eon to come back to France only as a woman—D’Eon’s court-ordered gender re-assignment effectively politically neutered a dangerously out-spoken celebrity, for one thing, and for another, Beaumarchais had bet a lot of money on d’Eon’s gender being exposed as female. D’eon, says Burrows, is “to some extent being tricked into a position; he’s able to milk certain advantages, but it wouldn’t have been his first choice.”

Burrows does agree that d’Eon’s later writings reflect the kind of penitent decision-making Kates believes was at the heart of d’Eon’s transition—but more of “retrospective moral justification” than anything else. “I disagree with Kates to some extent because I don’t think it’s worked out in advance, or even as he goes along,” Burrows says.

By the end of her life, it seems clear that she identified as a Christian woman. But the question of D’Eon’s agency in her transition is central to understanding what kind of legacy she leaves behind, and it is something we’re unlikely to ever really know. So what d’Eon means, what we project on to her, is dependent on contemporary gender and social politics.

In d’Eon’s own lifetime, feminist pioneer Mary Wollstonecraft heralded her as proof that women could outstrip men if given the opportunity. A 19th century biographer would claim that d’Eon was simply cross-dressing in order to better seduce married women, reinforcing some kind of macho, masculine ideal; in the 20th century, d’Eon’s story was analyzed in psycho-sexual terms and early sexologist Havelock Ellis coined the term “Eonism” to describe transvestitism. In the 21st century, she’s become a transgender heroine—the Beaumont Society, a support organization for the transgender community, has taken her name in admiration (the Society did not return an email for comment)—as well as an anime star.

An engraving from 1787 of Mademoiselle la Chevaliere d’Eon. (Photo: Wellcome Images, London/CC BY 4.0)

Burrows has struggled with how to make sense of d’Eon’s life. “In some ways, he leaves less of a legacy than we might think,” he says, “He doesn’t leave a set of followers, he doesn’t leave a number of people who behave the same way, but he is important in terms of how people are beginning to define themselves.”

Kates is less equivocal. “I think what makes d’Eon so historically significant and such an important pioneer for today is not what he did but the extent to which he thought about it and gave ideas to it,” he said. In d’Eon’s philosophy and to some extent, the philosophy of 18th century European society, gender is not essential, it is fluid; one can make a decision about where to land in a kind of continuum, not only of gender but of morality as well. “This whole discussion we’ve been having the past 6 months about which bathrooms people should use and where we’re groping towards is that a person should use the bathroom they feel most comfortable with, society shouldn’t be making that decision for them, this is right out of 1750s thinking,” says Kates.

D’Eon is a complex figure, whether that figure is dressed in a Dragoon Captain’s uniform or a Versailles ball-gown. Perhaps d’Eon was a victim of the power of an unchecked political state. Perhaps it’s simply that she was a woman, a person, so ahead of her time, that it’s taken more than 240 years to catch a glimpse of what she was trying to do.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook