The Sex-Obsessed Poet Who Invented Fascism

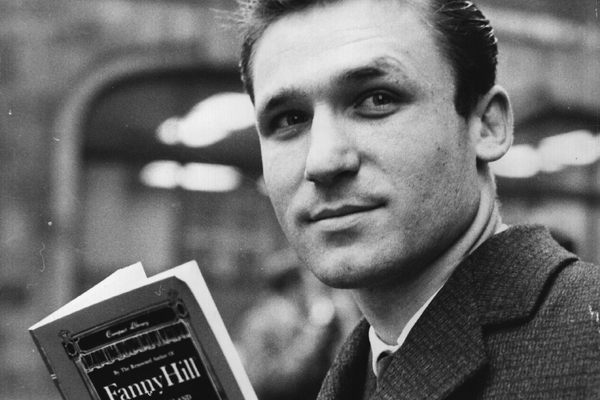

Gabriele d’Annunzio reading. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

It can be hard to reconcile the incredible charisma of Hitler written about in history books with recordings of his speeches in which he looks like a madman. Some might conclude that perhaps Germans didn’t notice how off-putting he was because his style of declamation was widely used at the time and has simply fallen out of fashion.

But Hitler’s speeches weren’t normal or spontaneous. Neither were Mussolini’s. Both of them were to a large extent imitating one man: an Italian poet named Gabriele d’Annunzio, who lived between 1863 and 1938. He was a war hero and famous libertine, and he essentially invented Fascism as an art project because he felt representative democracy was bourgeois and lacked a romantic dramatic arc.

D’Annunzio was a thrill-seeking megalomaniac best described as a cross between the Marquis de Sade, Aaron Burr, Ayn Rand, and Madonna. He was wildly popular. And he wasn’t like anyone who came before him.

A photograph of the shield on the door of Pescara’s commune (town hall). The text reads “Citta Dannunziana”: d’Annunzioish city. (Photo: Romie Stott)

“You must create your life, as you’d create a work of art. It’s necessary that the life of an intellectual be artwork with him as the subject. True superiority is all here. At all costs, you must preserve liberty, to the point of intoxication,” d’Annunzio writes in Il Piacere, an ambiguously autobiographical novel published in 1889. “The rule for an intellectual is this: own, don’t be owned.”

Italian cultural histories say d’Annunzio brought Italy into the 20th century. More accurately, he introduced Italy to nihilism. He glorified a world of the senses, pleasure and beauty at all cost. (Conveniently, these costs were often fronted by other people. He was continually bankrupt.)

He proposed an ethic of intense feeling, decadent and proto-Futurist: sex and violence, even if they hurt people, were ultimately good because they were beautiful and sensational—the more baroque, the better.

Eleanora Duse, one of d’Annunzio’s lovers. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

In his day, d’Annunzio was famous for his romantic escapades–he carried on with the well-known actress, Eleonora Duse, among many others, and detailed his almost compulsive sexual experiences in his fiction–and for writing plays so controversial that they caused fistfights among actors and audience members. One play, La Nave, suggested Italy go to war until the Venetian Republic was restored, a threat the Austrian embassy took seriously enough to protest.

Once he was famous enough, he got himself elected to the Italian parliament, essentially to prove he was very famous. (That was pretty much his campaign.) Once in Parliament, he used the opportunity to make speeches about how brilliant he was and how democracy was foolish because the average person is dumb.

He felt the state should get out of the way of the brilliant people, plus maybe engage in perpetual imperial expansion because war is a beautiful and glorious crucible. He was not re-elected. But that was fine with him: he found legislating boring and insufficiently ideologically pure. He was still very popular.

Gabriele d’Annunzio, with another officer, 1915. (Photo: Library of Congress)

When World War I broke out, d’Annunzio immediately urged Italy to take over everywhere. Although he was in his 50s, he went to the front to lead the charge, hopping from service to service. He commanded bomber squads as a fighter pilot. He led daring cavalry campaigns. He led an impossible naval raid that didn’t manage to torpedo much of anything, but did leave behind self-aggrandizing propaganda in waterproof ink. He repeated the trick by air, dropping 50,000 leaflets on Vienna. He did not bother to translate them into German.

D’Annunzio was terribly disappointed when the war ended. He took a few hundred troops and invaded the former Austro-Hungarian city of Fiume (modern-day Rijeka, Croatia), and declared it an independent country with himself as the ruler. His rationale? The city was 65 percent Italian, and the new state would ostensibly “help” oppressed nationalities around the world, like the Irish, Egyptians, and a few Balkan separatist groups.

Being d’Annunzio, he of course turned it into a sex-positive corporatist libertarian art commune. For 15 months. In the aftermath of a long war of attrition, nobody but d’Annunzio wanted to jump back into battle—and Fiume’s eventual nationality was still on the negotiating table.

Rijeka, Croatia, known as Fiume, which d’Annunzio invaded. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

D’Annunzio believed that a country was sustained by faith, not trust. Therefore, instead of trying to govern kindly or honestly, he thought a leader should act like the head of a religion—not simply a pope or grand mufti, but a Messiah. It’s unclear whether he structured his government as a personality cult because he thought it would be effective, or because he was so self-obsessed it was inevitable.

You’ve seen what it looked like, because you’ve seen the imitators. D’Annunzio made stylized, inflammatory speeches full of rhetorical questions from balconies flanked with pseudo-religious icons. He outfitted his troops in embellished black shirts and soft pantaloons, and told them to march through the streets in columns, palms raised in a straight-armed Roman salute that would be plagiarized by the Nazis.

He called himself Il Duce. He encouraged his troops to brutalize “inferior” people to rally everyone else’s morale, and attempted to found an Anti-League of Nations to encourage continual revolution instead of peace.

Mussolini in 1922. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

No one knows whether d’Annunzio exalted violence because of a Futurist pre-postmodern conviction that new structures could only emerge from complete destruction—modernity lancing the corrupted past like a boil—or whether he simply found the adrenaline arousing. Other of his governing ideals seem incongruously idyllic—music as a central duty of the state, enshrined in the constitution, plus nightly firework shows and poetry readings. In essence, he believed in government by spectacle.

Many artists of the time, including people who really should have known better, thought it was a daring and provocative thought experiment that should be allowed to continue indefinitely. Nevertheless, Italy itself eventually besieged Fiume (or as d’Annunzio styled it, Carnaro) and demanded d’Annunzio step down.

He responded by declaring war on Italy and leading dashing pirate raids to steal supplies. This too was surprisingly popular with the Italian people. The Italian army had to shell the city for five days to force a surrender.

D’Annunzio’s birth museum house in Pescara. (Photo: Raboe001/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.5)

D’Annunzio withdrew into semi-retirement after 1922, when an unknown assailant pushed him out a window in Gardone Riviera, badly crippling him. (Or possibly he just fell. He was taking a lot of cocaine.)

Mussolini, by then a rising political star, showered him with money and half a battleship lodged in a hill—either because Mussolini was genuinely a huge fan, or because he thought it was politically expedient to be viewed as a huge fan. (Why a half battleship? Because it makes a cool lawn ornament.)

D’Annunzio was dubbed Prince of Montenevoso and honorary general of the Air Force. He used his spare time and any spare money to further augment his already grandiose estate, “the shrine of Italian victories,” which included an office with an extremely low door so that those entering had to bow to him. He finally died of a stroke in 1938.

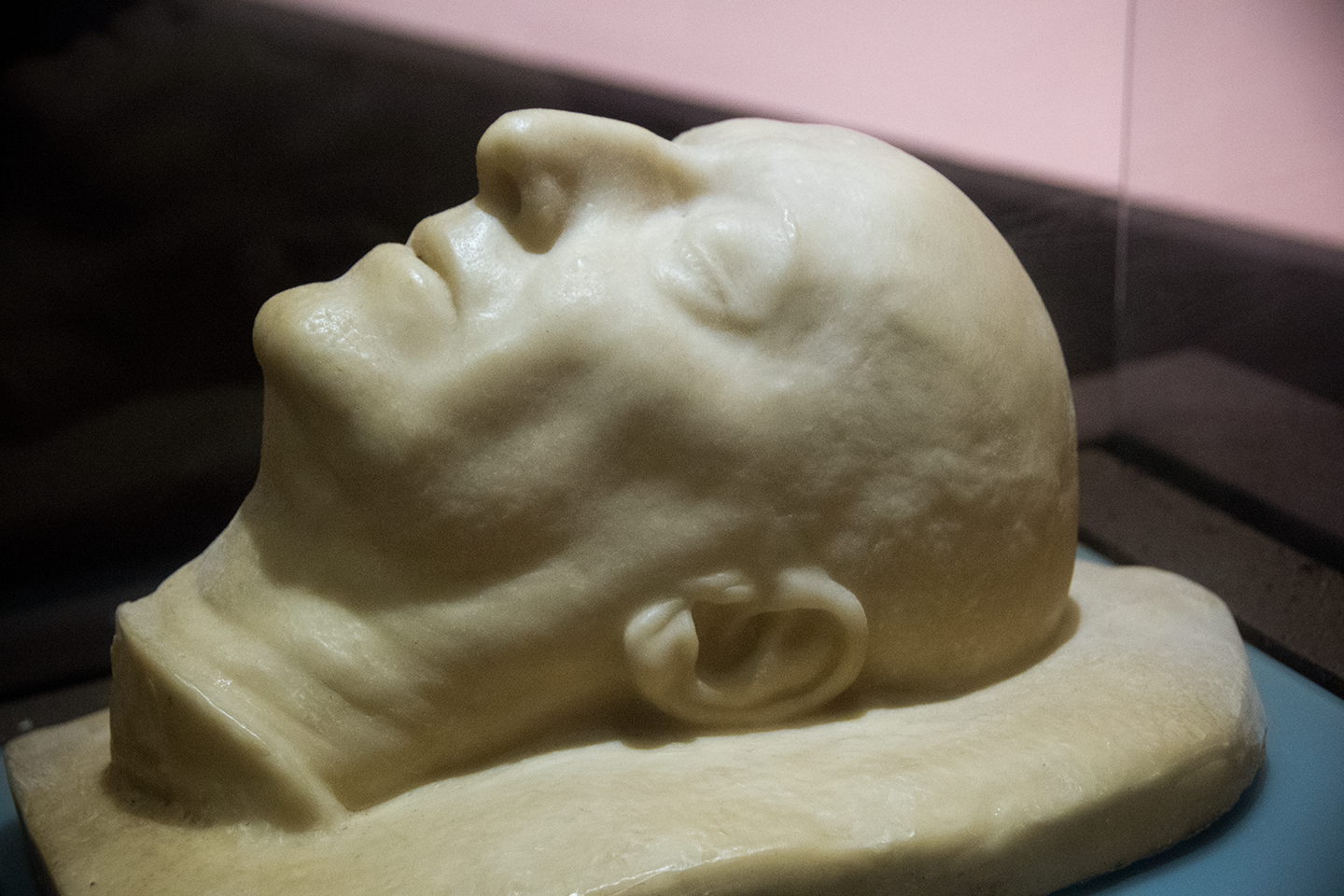

Sculptor Arrigo Minerbi made a wax cast of d’Annunzio’s face shortly after his death, used to produce this plaster head. (Photo: Romie Stott)

In Italy, and especially Pescara, his birthplace, he’s still very famous. Within two miles of my Pescara apartment, there are two d’Annunzio universities, one d’Annunzio music conservatory, a library, a gymnasium, a chess club, a bakery, a soccer field, and a bus line, not to mention a museum which lovingly preserves his birthplace and old clothes.

For me, it feels like running around a town where everything’s named for Charles Manson. For Italians, he’s the guy who wrote a poem about cake, who was once the country’s most famous literary figure (now overshadowed by a few eccentricities).

If you visit his birthplace, you’ll see his childhood rocking horse and some beautifully tailored suits. And if you want to move your four-year-old to Milan, Motta Sant’Anastasia, San Vito Chietino, Jesolo, or Lanciano, you can enroll her at a preschool named after Gabriele d’Annunzio.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook