The Singer Who Topped Charts by Embracing His Stutter

Scatman John was more than a one-hit wonder.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

The boy that would become Scatman John had a hard time growing up.

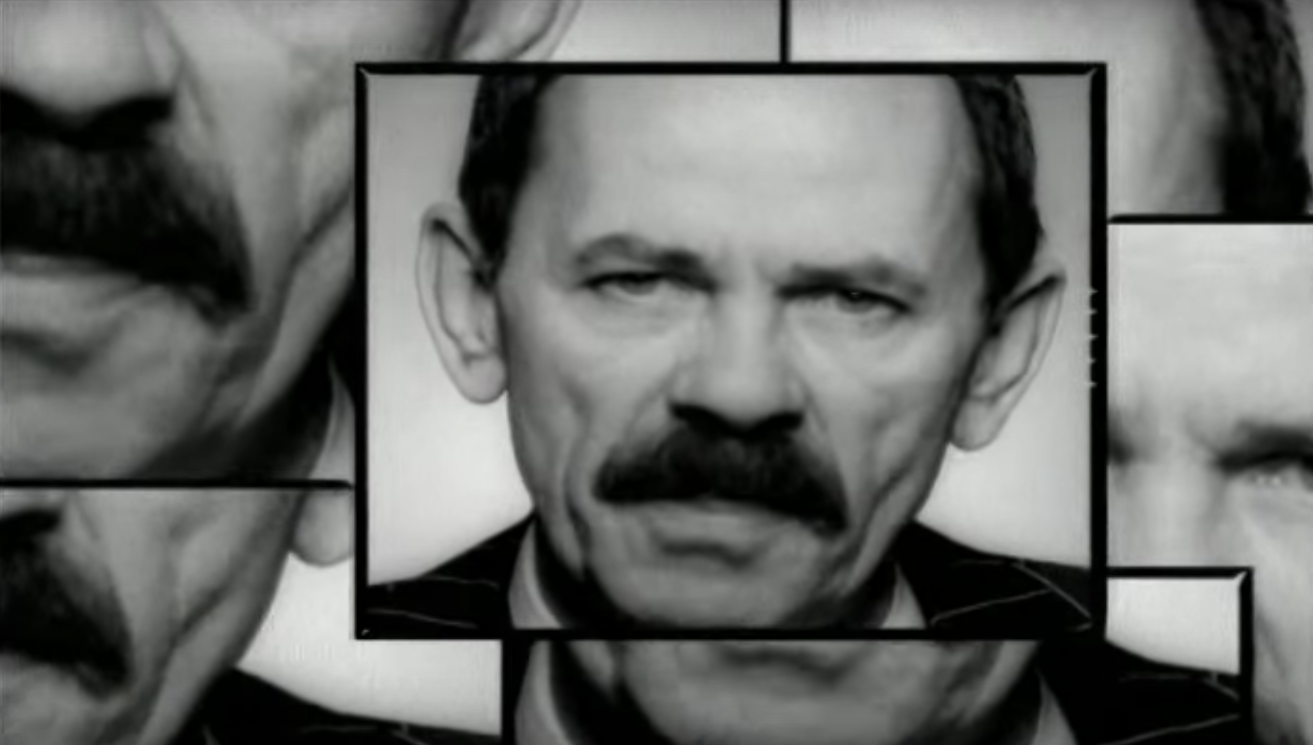

Before his massive international hit “Scatman (Ski Ba Bop Ba Dop Bop),” before selling millions of records globally in a style of music that hadn’t been popular in generations, and before he entered the National Stuttering Association’s hall of fame, Scatman John was just a kid in suburbia, born John Paul Larkin in El Monte, California in 1942, developing a stutter early in life that made communicating with others very difficult—and got him bullied.

“As a child, I had to fight a few times,” Larkin said in a 1995 interview with Advance for Speech Pathologists and Audiologists Magazine. “I went into a rage a few times. I remember one instance where some neighborhood kids … mock[ed] my stuttering at the top of their voices. That really hurt. It just crushed me. I waited until the next day when they had forgotten about it. I didn’t. I ran after them, and the rage was so strong I would have killed them if my father hadn’t stopped me. But that pain, I hope, has made me into the good person that I try to be.”

Larkin instead turned to music, which became a nonverbal source of creative expression, later gravitating toward jazz piano. He first learned about the scat style of singing listening to Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald. He worked as a musician—fairly anonyously—for decades, playing piano bars and festivals, until he finally released a self-titled album under his birth name at the age of 42. The album did not sell well, and by 1990, John decided to give his career one last push, moving to Berlin with his wife.

“After several months of going through the usual trials and tribulations of moving to another country and overcoming culture shock, Judy and I managed to secure an agent and I began to get booked into a European hotel circuit and I was well on my way to becoming the best hotel pianist I could be,” Larkin said once. “My feelings were … ‘Success at Last’ … I was so grateful to have actually had the opportunity to make a living as a musician. This, I thought, was as good as it could get.”

In Europe, he found greater acceptance of jazz, which inspired enough confidence that he incorporated singing into his act. Larkin reportedly received standing ovations for some of his performances.

“I began to own that I really could sing, that I was good,” Larkin said, according to the Los Angeles Times.

And once he found that confidence, things changed quickly for him, as his growing musical reputation eventually led to a music contract with BMG Hamburg, which had a unique idea to incorporate his jazz scatting with the house music dominating Europe at the time.

Eventually, he was teamed with producer Antonia Catania, who helped Larkin, then 53, create the surprise hit, “Scatman (Ski-Ba-Bop-Ba-Dop-Bop)”.

A uniquely ‘90s blend of jazz scatting, rap, and house beats, “Scatman (Ski-Ba-Bop-Ba-Dop-Bop)” was released along with a video that made the rounds on MTV.

Though the song caused little reaction upon its initial release, steady airplay on mainstream radio gave it enough momentum to chart in two dozen countries, reaching number one in twelve of them, including Canada, Italy, and France. In the U.S., the single got has high as number 60 on the Billboard Hot 100.

And fueled by the massive popularity of the song, the album Scatman’s World would go on to chart in 24 countries, including Canada, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

In addition to strong album and single sales, Scatman also found a home for his music in entertainment and advertising. “Scatman (Ski-Ba-Bop-Ba-Dop-Bop)” was used in a Good Humor ad campaign and the 1996 Martin Lawrence/Tim Robbins buddy road comedy Nothing To Lose. As perhaps the ultimate sign of ‘90s pop culture respect, the video was even featured in an episode of Beavis and Butthead.

“There should be a name for this kind of music,” Beavis notes.

“There already is a name for this kind of music, it’s called ‘crap,’” Butthead replies.

Scatman John might have just been a one-hit wonder except that his third album, released in 1997, became an unexpected hit in Switzerland and Japan, selling well over a hundred thousand copies.

And it was in Japan where Scatman John truly came into his own. He sold 1.56 million copies of Scatman’s World in Japan alone—where it is the 11th-highest-selling international album of all time.

And with that level of success, he became something of a pop phenomenon, appearing in commercials. He even received his own impersonation, complete with trademark fedora and mustache on the iconic television series, Ultraman. He’s also the example used by TV Tropes for “Big in Japan.”

Unfortunately, it would be Scatman John’s last moment in the limelight. He was diagnosed with lung cancer shortly after the release of his third album, but continued touring until his death in 1999.

From start to end, his career as a pop star lasted four years. But he embraced every moment of it, taking advantage of the platform he had to speak about the issues he really cared about—like stuttering, the subject of his most famous song.

“The fact that I’ve been a stutterer since I’ve been speaking has compelled me to find another way to speak another language,” he said in a speech to the National Association of Communicative Disorders. “My greatest problem in my childhood is now my greatest asset. I’m trying to tell the kids today that Creation gave us all problems for a purpose, and that your biggest problems contain a source of strength to not only step over those problems, but all our other problems as well.”

Andrew Egan is writer and editor of Crimes In Progress. A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook