These Volcanoes Have Humanity On Their Hit List

The Mayon Volcano spews gas over the Philippines in 1984. [Photo: WikiCommons]

The Mayon Volcano spews gas over the Philippines in 1984. [Photo: WikiCommons]

Picture a volcanic eruption, and explosive noises, torrents of bright lava, and sky-choking clouds of smoke comes to mind. But although there are immediate consequences when a volcano blows its top, the longer-lasting effects can be even more destructive. Using a mix of cutting-edge technology and old-fashioned sleuthing, a multinational team of scientists from the Desert Research Institute has puzzled out which volcanoes were responsible for some of history’s most catastrophic events, from devastating plagues to, potentially, the fall of the Roman Empire.

Certain types of erupting volcanoes spew huge amounts of sulfur, which, when it hits the atmosphere, combines with water to form aerosols that reflect sunlight back into space and cool the earth’s surface. Sulfuric acid aerosols are so effective that some climate scientists think we could mitigate climate change by pumping it into the atmosphere ourselves.

Yet long before that was even an option, the volcanic anti-blankets wreaked havoc on huge swaths of the world, triggering “crop failures and famines… pandemics, and societal decline,” the researchers said in a statement.

An aerial view of the Chiltepe Peninsula, once home to a volcano that chilled the world in 44 B.C. [Photo: WikiCommons]

An aerial view of the Chiltepe Peninsula, once home to a volcano that chilled the world in 44 B.C. [Photo: WikiCommons]

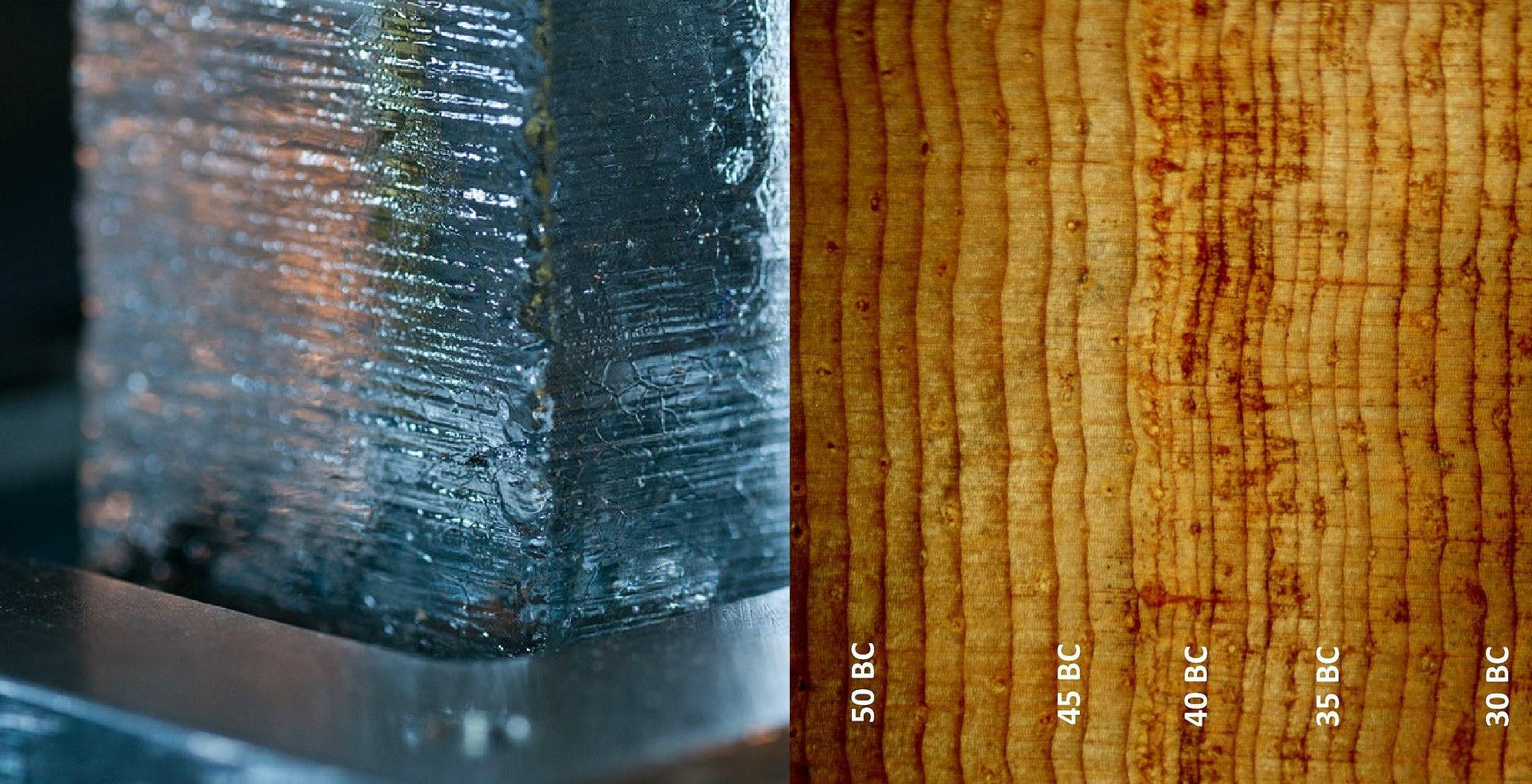

To see which volcanoes were the most vicious, the researchers needed to match up eruptions with their long-term effects. To do this, they cross-referenced several very different types of information: ancient manuscripts, tree-ring chronologies, and new data gleaned from ice cores taken in Greenland and the Antarctic.

For example, Germans in 939 described living for months under a sun that “did not have any strength, brightness, nor heat… Indeed, we saw the sky and its color changed, as if flushed.” The culprit? The Icelandic volcano Eldgja, which the team’s “state-of-the-art, ultra-trace chemical ice-core analytic system” revealed had gone off a couple of months earlier.

Overall, the researchers were able to put together a timeline that correlated “fifteen out of the sixteen coldest summers” between 500 B.C.E. and 1000 A.D. with large eruptions that had happened just before. They also made a chart ranking the top twenty-five climatically destructive volcanoes of the past 2,500 years. Some of the more famous eruptions—Pompeii comes to mind—didn’t even crack the list, which is topped by Samalas in Indonesia (which caused famine, pestilence, and months of cloudy skies in Europe), a volcano that made a huge caldera in Nicaragua, and an unnamed behemoth from 426 B.C.

Researchers used a combination of ice core and tree ring data to more accurately date the eruptions. [Photos: Sylvain Masclin and Matthew Salzer/Desert Research Institute]

Researchers used a combination of ice core and tree ring data to more accurately date the eruptions. [Photos: Sylvain Masclin and Matthew Salzer/Desert Research Institute]

In the process, they solved a long-running mystery about what caused the Plague of Justinian, a pandemic that killed forty percent of Constantinople between the years of 541 to 542. Previous theories had been stymied by disagreements between the “ice core and tree ring communities,” lead author Dr. Michael Sigl told Nature.

The new analysis blames the clammy weather that led to the plague on two eruptions, one in the northern hemisphere, and one in the tropics. The same extreme cooling may have contributed to worldwide geopolitical shifts in the sixth century, including the declines of the Roman Empire and the powerful Mesoamerican capital of Teotihuacan, in modern-day Mexico.

The researchers hope that these new techniques will allow them to look back even further in time—the goal is the last Ice Age, which ended about fifteen thousand years ago. For now, humans had better start keeping an extra eye on volcanoes, which are clearly plotting our demise even when they seem to be asleep.

Teotihuacan was a thriving city until droughts decimated the population in the 6th century, right after a one-two eruption punch. [Photo: WikiCommons]

Institute of Desert Research scientists retrieve a freshly drilled ice core in Greenland. [Photo: Olivia Maselli/Desert Research Institute]

Institute of Desert Research scientists retrieve a freshly drilled ice core in Greenland. [Photo: Olivia Maselli/Desert Research Institute]

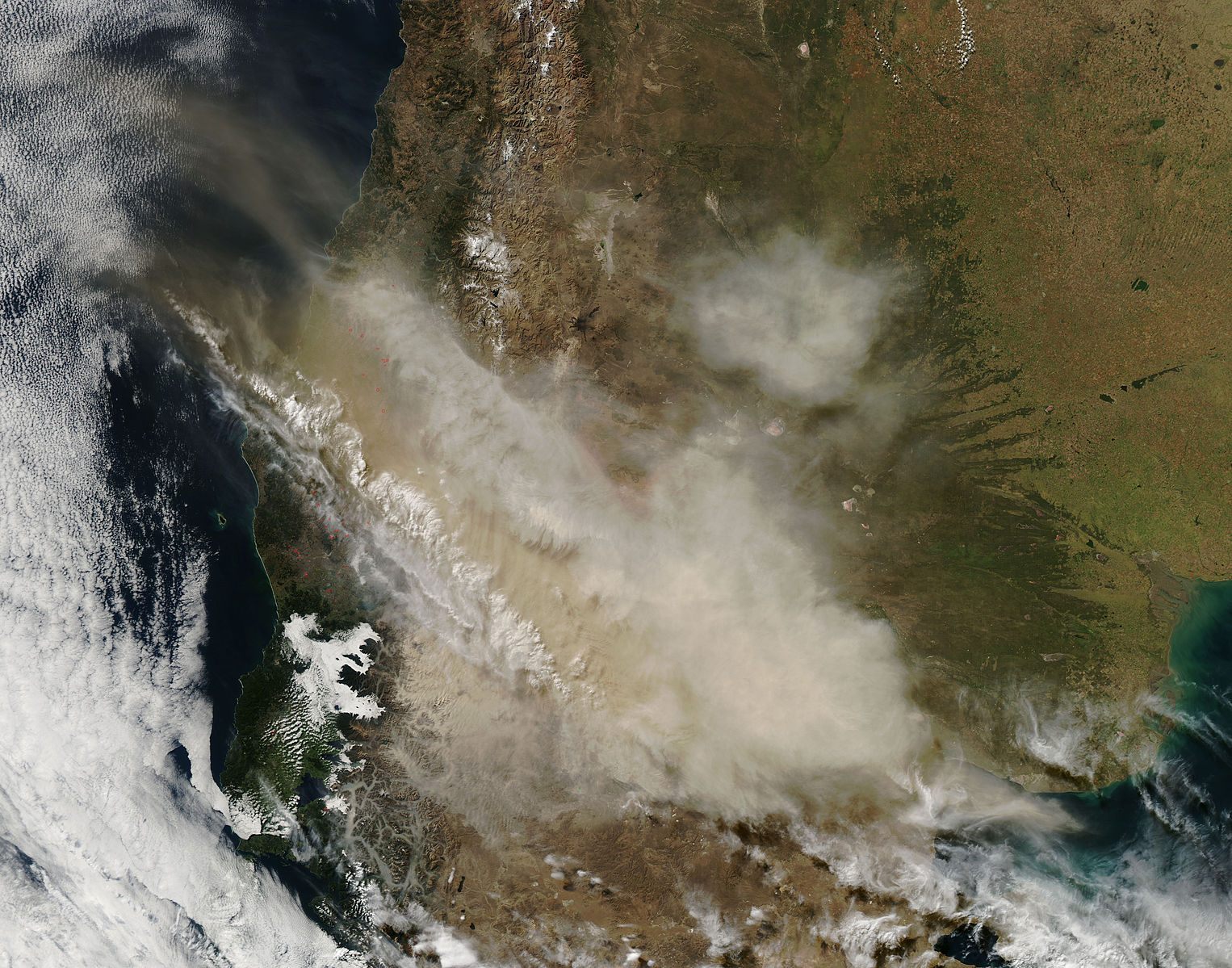

An ash cloud spreads over Chile’s Calbuco Volcano during its eruption earlier this year. [Photo: WikiCommons]

An ash cloud spreads over Chile’s Calbuco Volcano during its eruption earlier this year. [Photo: WikiCommons]

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook