What Color Is Night?

What you see overhead is a combination of where you are, how our vision evolved, and that flimsy layer of atmosphere that keeps us all alive.

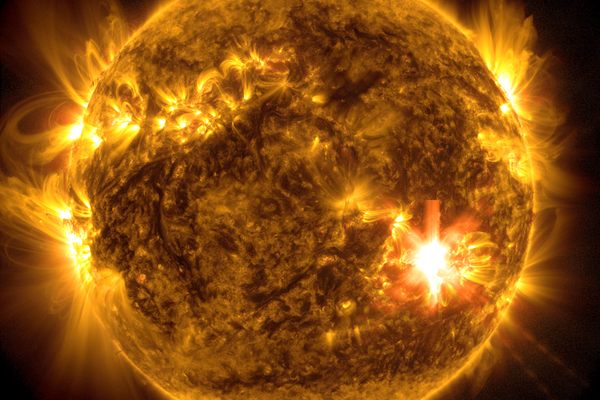

Ask any preschooler to color the sky, and they will probably reach for a blue crayon. If you ask an adult to describe Earth, they will mention that same hue; the most famous descriptions of our planet call it a “Blue Marble” or a “pale blue dot.” The sky looks blue to our light-limited eyes because during the day, sunlight scatters through Earth’s watery atmosphere. Pure sunlight is pure white light, a combination of every color, but viewed from Earth, the sun’s green, yellow, indigo, and other colors are largely absorbed. The light that scatters the most, and which dominates our vision, is blue. So, unless you grow up where it’s cloudy and slate-gray all the time, the simple answer to coloring the day sky is blue.

But what color is the sky at night?

It’s tempting to say black, or grayish black, or some variation of a color that really just conveys the feeling of darkness. But the truth is more complicated, and it depends on what time you’re asking, where you’re sitting, and whether the Moon is out.

The sky is never empty of color, not even at night, at least if you’re on Earth.

First, a word about vision. We have several types of cells in our retinas, which is a nerve-filled layer of tissue at the back of your eyeball. There are two primary types, called rods and cones for the way they look in a microscope. Rod photoreceptor cells detect light, and cone-shaped cells detect color.

Rod cells can detect just a few photons of light (really). Cones are about 1,000 times less sensitive, so they need much more light than rods to pick up any color signals. This is why even brightly colored clothing looks muted gray in a dark room. The color is not gone; your eyes’ ability to perceive it is just diminished. The darker it gets, such as during twilight, the more color seems to bleed out of the world. When it’s really dark, you cannot detect color at all; you may wonder if there is any color to see, the way you might wonder if a falling tree can be said to make a sound if there is no one to hear the crash. In the darkness, debate about color becomes as much about philosophy as about optics. But color is there.

In the night, when the Sun is on the other side of Earth, there is not enough light in the sky to stimulate the cone cells in your retina. So the sky should look black. But it often does not, and for that you can thank the flimsy yet vital layer of this planet that keeps you alive: the sky itself.

When you are in a city, the sky might look yellowish or whitish. This phenomenon is known as skyglow. It happens because of a similar physical phenomenon that turns the sky blue. Light bounces off molecules and particles in the atmosphere, and reflects back toward the ground. In hazy places, or in places with a lot of artificial lighting, the night sky can look slightly milky.

Moonlight also illuminates the night sky, especially when the Moon is full or mostly there. Its effect can be more evident on objects than on the sky itself; treetops and buildings can appear to be dipped in milk, but the sky itself is blue.

In open country away from a city, the blue of a moonlit sky is maybe more like lapis or navy, rather than baby blue or summer-afternoon cerulean. That’s because moonlight is reflected sunlight, though its apparent brightness is about 400,000 times weaker than that of the Sun. Moonlight scatters in the same manner as sunlight, so the molecules in the atmosphere make the nighttime sky blue, too.

On the Moon itself, the sky, as it were, is totally black, because there is no atmosphere to scatter any light. There is no sky, really, in the way that you would experience sky on Earth. There’s just emptiness, dotted with the white lights of distant stars. While on the Moon, astronauts saw the grayscale landscape of the lunar surface, and a wide range of colors in the rocks and in their surroundings, but they saw only darkness above.

On Earth, even in the absence of light pollution or a Moon, the sky is never totally black. Instead, a rainbow of subtle colors appear, although they are more prominent when captured by cameras, both in space and on the ground. Bands of green and red appear through the dark, a phenomenon called airglow. Rather than the light of the Sun or Moon, this is the light of chemistry: Solar radiation energizes atoms and molecules of air, which emit a faint glow. So sometimes the night sky is reddish green, or teal, or purple. And that’s saying nothing of auroras.

To me, the answer that gets closest to the truth is that the night sky does not have a color. The atmosphere of our planet is what holds the color. We are not just seeing the stars themselves; we are seeing the emptiness of the space around them, but attenuated through Earth’s sky. What you really see is the sky, which is still Earth, still our home.

I think of the night as a portal to the rest of the universe. The open blue sky of day, while it is just as exposed to the universe, feels like it is a part of Earth, as much as the wind and the rain. The night sky does not feel this way. Instead, it feels like space. When you are lucky, and somewhere dark and clear, the sky looks like the pictures you see from the Hubble or James Webb space telescopes.

But it is still seeing the universe as if through a shroud. The presence of color is your reminder that you are here, on Earth. We are all in the void, surrounded by a great enveloping cosmic dark, but on Earth, you are home.

Wondersky columnist Rebecca Boyle is the author of Our Moon: How Earth’s Celestial Companion Transformed the Planet, Guided Evolution, and Made Us Who We Are (January 2024, Random House).

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook