Antarctica’s Largest Native Land Animal Is Actually Rather Tiny

Meet the mighty midge.

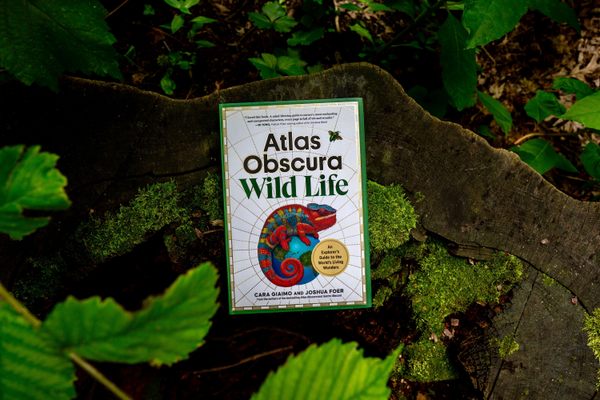

Each week, Atlas Obscura is providing a new short excerpt from our upcoming book, Wild Life: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders (September 17, 2024).

In most places, midges don’t command much respect, inspiring annoyance and vague shooing motions and disappearing by the billions into the mouths of larger creatures.

At the bottom of the world, though, everything is topsy-turvy. The Antarctic midge is the largest land animal endemic to the continent. In other words, Africa and Asia have elephants, North America has bison, and Antarctica has the midge.

Antarctic midges are flightless, long-limbed, and about the size of sugar ants. They live in ice-free areas near colonies of seals and penguins, who bring nutrients to Antarctica’s otherwise low-cal soil by going out to sea, eating lots of fish, and coming back on land to poop. Mosses and other plants grow in this soil, and the midges eat these plants as they decay. Because nothing eats them in turn, they are, in a way, at the top of their little food chain—another strange place for a midge.

The species has endured a lot to take this high position. About 40 million years ago, when Antarctica first split off from South America and began to drift, “there were probably thousands of insects living down there,” says Nicholas Teets, an entomologist at the University of Kentucky and an expert on the midge. As the continent became colder and drier, the rest of them died off. Somehow, these midges persisted, even through long periods when their entire home was layered thickly with ice. They may have found tiny thawed pockets or hunkered down underneath the glaciers, Teets says.

In the process, the midges evolved an arsenal of strategies that allow them to live relatively comfortably. They got rid of their wings—likely to reduce heat loss, along with their chances of getting blown away—and a lot of extra DNA in their genome, giving them one of the smallest known genomes of any insect. Their streamlined genetic toolkit is focused on metabolic control and environmental responses and underlies a mysterious Popsicleification process that allows the midges to dehydrate themselves and literally freeze. Unlike their northern cousins, who can be born and die in a single season, Antarctic midges take two years to go from egg to adult, emerging to feed only in the relatively balmy summers (which last from December through February) and spending the rest of their time frozen underground.

These midges do have something in common with others, though: They form their own kind of swarm. When hunting for study subjects, Teets and his colleagues sometimes find up to 40,000 larvae in a single desk-sized patch of dirt—a gathering of future kings.

Range: Antarctica’s northwest peninsula and surrounding islands

Species: Antarctic midge (Belgica antarctica)

How to see them: Look for a wet, iceless area with some moss and grass, and start flipping over rocks.

Wild Life: An Explorer’s Guide to the World’s Living Wonders celebrates hundreds of surprising animals, plants, fungi, microbes, and more, as well as the people around the world who have dedicated their lives to understanding them. Pre-order your copy today!

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook