The Forgotten Government-Funded Kids’ Books of the Great Depression

New Deal, new children’s literature.

The Works Progress Administration (WPA)—Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s nationwide effort to re-employ unemployed Americans during the depths of the Great Depression—conjures images of daring dam-builders and fearless steel-workers. But children’s books? Not so much.

Leave it to FDR and his stable of advisors to defy expectations.

While legions of laborers collected government paychecks for their contributions to massive infrastructural projects, thousands of idle creatives also hit the pavement on Uncle Sam’s dole. They, however, were commissioned to create a different type of public work: diverse portraits of the country’s past and present in pen, paint, and photographs. These were the employees of Federal Project Number One (aka, “Federal One”), the cultural wing of the WPA, which included a select group of children’s authors, illustrators, and editors.

Federal One’s five divisions dispatched authors and artists from state-based offices with the broad aim of sponsoring projects that served the public good. With this mandate, the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP) produced 276 volumes and 701 pamphlets, amounting to over 3.5 million individual items. Its archive includes extensive folklore and oral history collections (2,300+ recorded interviews with formerly enslaved people, among other life histories), as well as the renowned American Guides Series, which was conceived as a way to document local cultures threatened by the rising tide of commercialism. Contributors included many then-unemployed writers who later became giants of American letters; the Illinois office alone employed Margaret Walker, Studs Terkel, Nelson Algren, Richard Wright, and Saul Bellow.

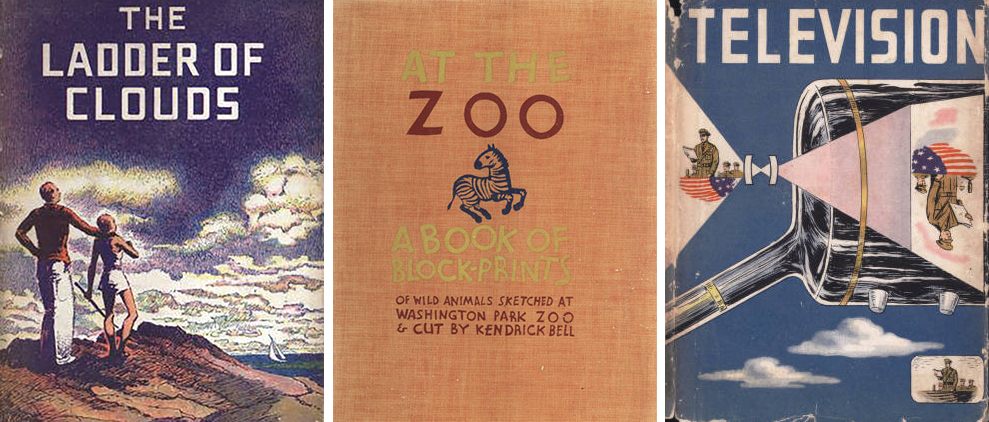

While the guidebooks have been feted by figures ranging from John Steinbeck (how he so wanted to bring them all on his cross-country travels with Charley!) to Michael Chabon (essential in researching The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay), other pieces of FWP writing have largely faded from memory. Those forgotten works include children’s books from three regional offices—New York City, Philadelphia, and Milwaukee—that produced diverse texts for juvenile readers.

New York’s New Reading Materials Program launched in 1936 with a run of cheaply produced typewritten, mimeographed texts designed to entice rough-and-tumble city kids, who, according to a New York Times account of March 15 of that year, were “largely inured to hard knocks.” The topics were engaging and of a variety of genres (realistic fiction, fairy tales, adventure serials, poetry, informational texts), the language was “living,” and the visuals striking. These materials were not made for instructional use by the teacher; rather, the intent was to build a desire to read for reading’s sake.

The program worked, and word of it traveled around the country. According to a 1937 St. Louis Post-Dispatch article on the New Reading Materials program, the NYC Board of Education soon began to receive fan mail from children eager to learn the fates of their favorite serialized characters, such as Alfred Sinks’ Tom Coe, Pirate. As the Post-Dispatch notes, the letter-writers “wanted to know … whether the pirates settled down to become home-loving folk or whether they were pardoned.” Such queries followed Sinks on his school speaking junkets, where he not only addressed questions regarding Tom Coe’s future but also found himself inundated with autograph requests.

With this type of reception, the program adopted better printing techniques and wider circulation: by the end of 1937, more than 21,000 copies of the books were in use among 140 city schools.

Kids—tentative and avid readers alike—loved the New Reading Materials. The stories are often dark, funny, and realistic, defying the unstated rule of writing for elementary-aged children that things always resolve for the better, that even when protagonists get lost, they generally find their way home.

Author Sulamith Ish-Kishor’s Meggie and the Fairies, is case in point. In it, happy, flower-picking Meggie Morrison drifts too far afield, is lured by a fairy’s siren song, and finds herself an ambivalent prisoner in an underground fairy kingdom. Rescue attempts ensue, but all fail. Meggie is released 100 years later to find the world changed: there’s no more home, no more family. Distraught, she returns to the hill of the fairies, where she cries herself to death, only to be reclaimed by the agents of her destruction who watchfully wait for her awakening. While there was no happy ending for Meggie, there was for Sulamith—she later wrote countless acclaimed works, including the 1970 Newbery Honor book Our Eddie.

Irving Drutman, who variously worked as a journalist, editor, theater critic, songwriter, and memoirist, also penned a volume that defied the happy-ending rule. The Proud Prince picks up after the ever-after, centering on the undoing of the eponymous Proud Prince and his equally vain and greedy wife. Mere pages into Drutman’s story, the prince ascends to the status of king. He and the newly minted queen begin a quest for the world’s most elaborate, heavily jeweled robe. In the process of assembling it, they bankrupt the kingdom and themselves. And the robes? Too heavy to wear, totally useless. As the depressed royals sit down to dinner in their aged robes, they’re stunned to learn that there’s no dinner—all the money for food went to finance their greed.

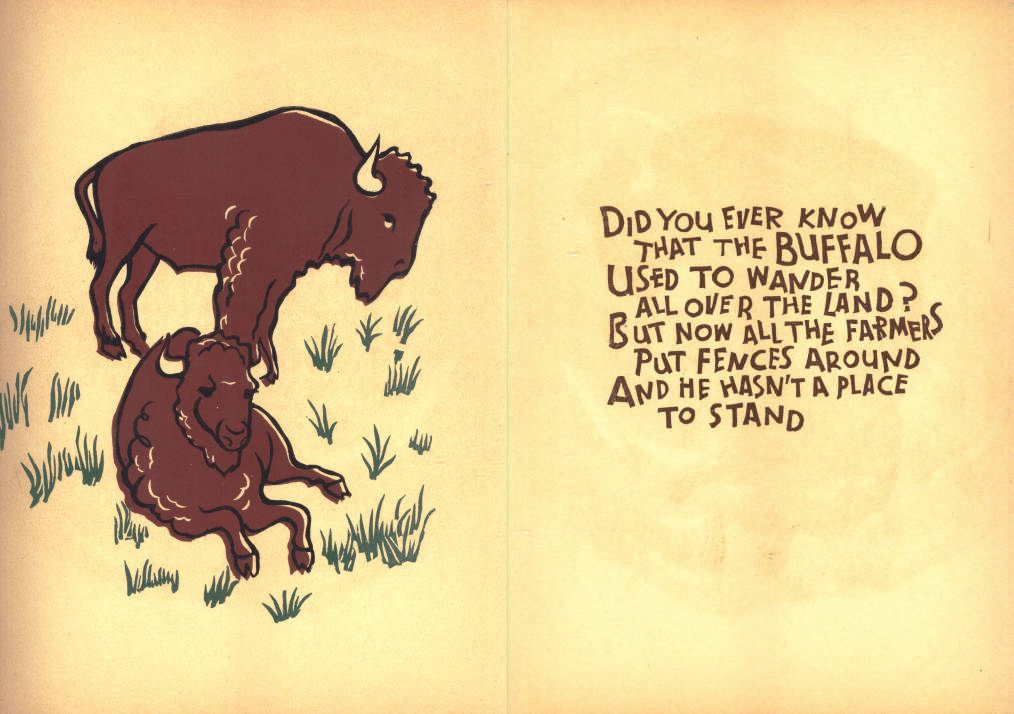

New York’s New Reading Materials Program had analogue units in Pennsylvania and Milwaukee that produced children’s books, although the purposes and intended audiences differed. At the Philadelphia office of the Pennsylvania Writers’ Project, the 39 informational texts of the Children’s Science Series were assembled in conjunction with the commercial publishing house, Albert F. Whitman. In Milwaukee, four primers—along with hundreds of toys, games, dolls, tapestries, and other furnishings—were created by more than 5,000 artists and craftspeople, mostly women, many African-American. While less is known about the authors of these volumes and their reception, they merit mention as works that the government saw fit to print in an era when the authorial need for a paycheck was wed to children’s needs for resources to educate and entertain.

To see more of the WPA Children’s Books, delve into the Digital Archives of Broward County.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook