About

The entrance to the imposing Mehrangarh Fort is guarded by a series of seven famous gates. To the left of innermost gate, Loha Pol, or "Iron Gate", are 15 small handprints left by the wives of the maharaja before they immolated themselves on his funeral pyre. Known as sati marks, the gilded handprints most likely date back to the 1843 death of Maharaja Man Singh.

The custom of sati has ancient origins in the Hindu faith, and was practiced widely in the Rajasthan area. Wives were dressed in wedding finery to join their husbands in death as an act of devotion and faith, usually within a day of his death. In 1731, following the death of Maharaja Ajit Singh six wives and fifty-eight concubines placed themselves in the funeral fires. The practice horrified early western colonials, and it was outlawed by the British in 1829, but was not officially condemned by the Indian government until 1987 when they passed the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, in the wake of a well publicized sati death. The last recorded case of sati in Jodhpur was in 1953.

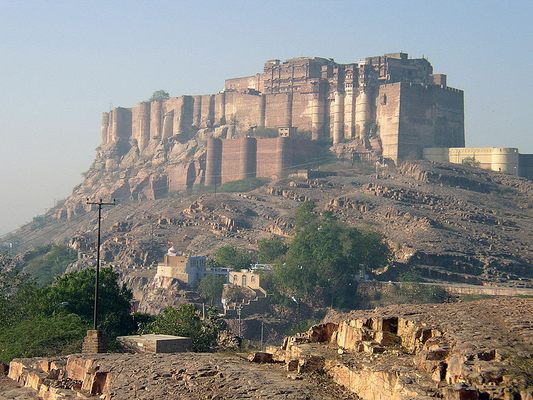

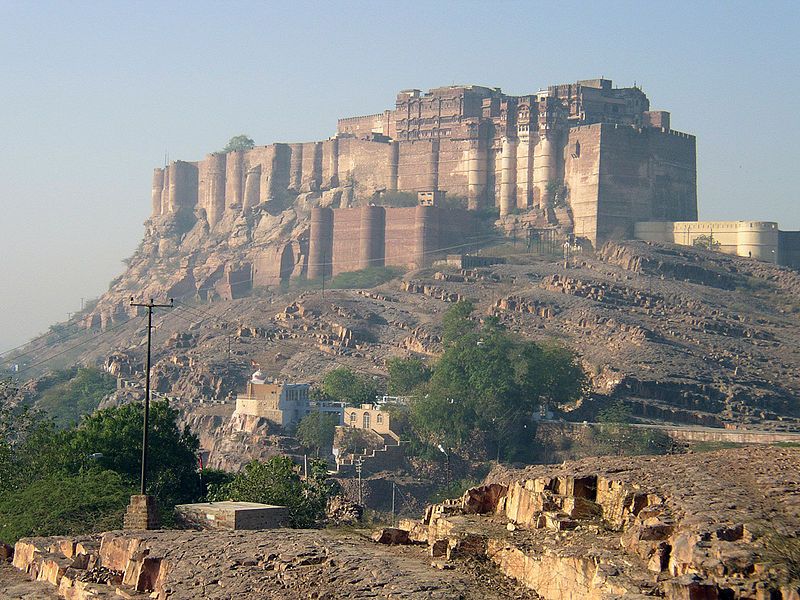

Overlooking Jodhpur as the home of maharajas since 1458, the Meghrangarh Fort has a particularly bloody history, starting with a curse placed during the construction by a hermit who had been living on the mountain. Irritated at being ousted, legend states that he cursed the builder, Maharaja Roa Jodha with threats of drought. To appease the hermit, Jodha built him other nearby accommodations. He then took the further precaution of burying a local man alive in the foundation. In exchange for his life, his descendants are cared for to this day by the state.

Other stories from the fort's history underscore a legacy of violence, primarily taking advantage of the extraordinary height of the fortress: 120 foot walls perch 400 feet over the valley below. Gravity played its gristly part in the death of a prince's mistress, hurled from a window, a Prime Minister pushed from the ramparts, and Maharaja Rao Ganga's opium fueled tragic accidental fall. In September of 2008, the bloody history was added to when a stampede at one of the fort's shrines left 249 people dead, and several more injured.

Most of the fort visible today dates from the mid 1600s, and throughout its history various rulers have left their mark on the architecture. Inside the fort opulently furnished palaces include a hall of mirrors, an armory, and displays of the trapping of the Maharajas such as turbans, palanquins, and ceremonial gold and silver elephant howdas (saddles).

Related Tags

Delhi and Rajasthan: Colors of India

Discover Colorful Rajasthan: From Delhi to Jaipur and Beyond.

Book NowCommunity Contributors

Added By

Published

October 7, 2009